Around forty Ukrainians arrived in Cazilhac, an Aude village of barely 2,000 inhabitants, at the start of the war in their country. Almost three years later, there are a dozen left, determined to settle in France.

“I was sure I kept it… Ah, there it is!” Olena takes a number from her dresser The Independent and unfolds it on the kitchen table. It is dated April 10, 2022. “We had just returned from Poland.”slips Jean-François, nostalgic on this mid-December evening. The double-page spread shows photos of a bus full of people, with 42 Ukrainians on board. War had just broken out between Moscow and kyiv when the mayor of the village of Cazilhac (Aude) decided to charter a bus to Presmysl to drop off boxes of food and pick up refugees at the border.

Jean-François, resident of the town, volunteered: “I had a bus license and acquaintances ready to finance the transport costs.” He recounts the nights of driving, the shock at the Polish border seeing businesses transformed into refugee camps, and the laughter too. The memories are more painful for Olena, a 42-year-old Ukrainian. “I was exhausted, exhausted”she repeats, her face closed. Originally from Donbass, she remembers the emergency evacuation with her son: two days in crowded trains and a lump in her stomach. “I stayed a little over a week in Poland. No shower and painkillers to help me sleep” she summarizes.

But her eternal smile chases away her pain as soon as she talks about her new life. Olena is one of a dozen refugees still living in this village of barely 2,000 souls. With Jean-François, who has since become his companion, they built a house there. “I learned how to install windows, placo, how to paint…” she exclaims as she walks around the owner.

Sitting in their kitchen over a drink, the lovers retrace their romance. Olena and the one she nicknames “Jef” found each other by chance five months after settling in with a host family. She remembers the apprehension at the beginning, her anxiety before opening her mouth, her French which she considered bad. “I came to pick you up from Ukraine by bus, and you were afraid to get in my car to go to a restaurant?”jokes Jean-François to the laughter of his partner.

Olena does not want “obviously” not leave. She landed a permanent job as a cleaner in a hotel in Carcassonne, a city bordering Cazilhac, and entered into a civil partnership with Jean-François. This makes her eligible for a residence permit longer than the renewable six months of temporary protection granted to Ukrainian refugees. From there to asking for asylum? This request can result in obtaining the right to reside in France for ten years (refugee status) or four years (subsidiary protection). “If my application is validated, I will not be able to return to Ukraine during the duration of my residence permit. There are still my parents there. I will perhaps go see them one last time before passing the milestone”she thinks.

“It’s been three years since I last saw my family. They are courageous, they tell me they are holding on.”

Olena, Ukrainian refugee in Cazilhacat franceinfo

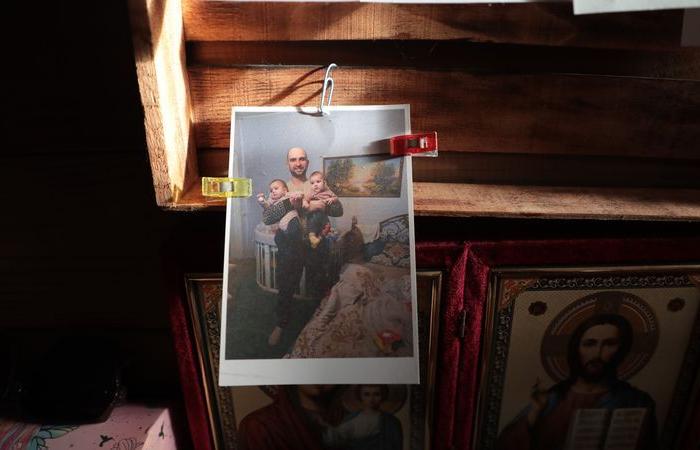

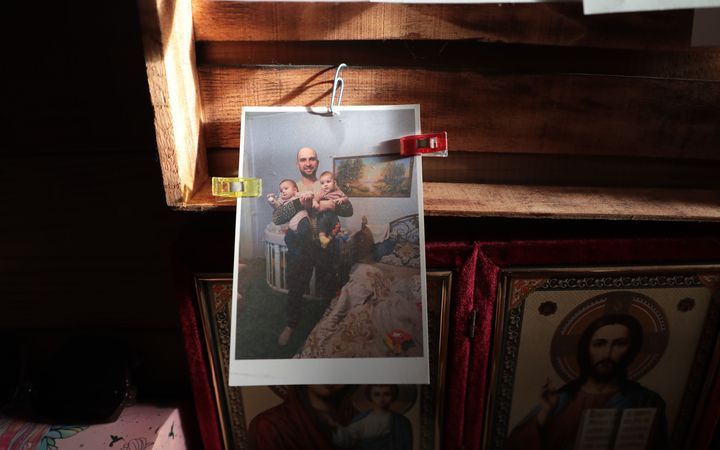

The Scherbakovs have drawn a line under their previous lives. In their bungalow, located on the old village campsite, only the Slavic dialogue spat out by the television suggests their Ukrainian origin. “Our house was bombed, we lost everything”breathes Olha, 33 years old, originally from Pokrovsk. Her mother-in-law remains silent: her home was also razed and her husband did not survive. There are now seven of them living in this house.

A few months after her arrival in Aude with her two eldest children, Olha returned to Donbass, because her husband Vladyslav, 33, had not been able to leave the territory. There, she gave birth to twin girls, bringing the siblings to four children. With more than three children to support, Vladyslav, who worked in the mine, was then able to escape mobilization. The destruction of their house made them decide to flee Ukraine for good. “I contacted the mayor and he told me to come back to Cazilhac”Olha remembers.

“We found this ‘chalet’ for them urgently, but it’s not ideal. We applied for social housing,” reports Toni Carvajal, the village mayor, who has never stopped watching over the refugee families. For example, he used his connections to find a place for Elena, 42, in a restaurant in Carcassonne. “For the moment, I'm working in the dishwasher“, grimaces the Ukrainian, drawing a burst of laughter from the mayor. This former secretary likes to imagine herself a saleswoman. “But I don’t have much choice at the moment, because of the language barrier”assures the one whose French is nevertheless fluent.

Olha and Vladyslav continue their apprenticeship. “Next week we will celebrate New Year”. With furrowed eyebrows, they note the words dictated by Karine, who gives us an amused look. The sixty-year-old goes to the Scherbakovs' house five times a week for language lessons. She was the one who hosted Olha and her children when they arrived in 2022. She looks at the father's copy: “You didn’t make too many mistakes.” “Accents, always…”he whispers. Vladyslav is a bartender in the same bistro as Elena: “It allows me to progress, but French is very difficult to learn.”

Enough to complicate the asylum application procedure. “I give them a hand to fill out the documents, but there are so many appointments”laments Karine. The interviews are held in Montpellier, an hour and a half by car from Cazilhac. Vladyslav can drive with his Ukrainian license for now. “But if they obtain subsidiary protection, they will have to retake it, because this diploma is not recognized by France. It will complicate their organization”continues the professor.

These everyday drawbacks remind us that Ukrainian refugees are not there by choice. “Ce What pushes you to leave is fear. The fear of being bombed, the fear of the Russians entering your home in the middle of the night, even more so when you are a woman…”Olena pours out, referring to the rapes committed by the men of Moscow. It is difficult to know the extent of the phenomenon, but a United Nations report, published in March 2024, denounces these crimes and NGOs speak of thousands of victims.

“We are even more afraid for the children. We fear that they will be taken by force to the front. There is only death waiting for us there”adds Elena, who came with her daughter. She says she saw her neighbors hiding the young men of their siblings, “because the Ukrainian police do not hesitate to come and pick them up directly from residents”.

Initially set at 27, the age of mobilization was lowered to 25 in April and the question of raising it to 18 arises. Olena's son was not yet an adult when they fled the country. “Now he's 19. He's looking for himself, but doesn't plan to go back. He tells me: 'Mom, I can't go fight, I can't kill'”she assures.

“If my son were drafted today, he would die right away. He is not trained for combat!”

Olena, Ukrainian refugee in Cazilhacat franceinfo

Toni Carvajal shoots his head: “I am a product of Spanish immigration. What they experienced, my grandparents experienced in Spain. They left because there was war, we would all have done it if it made us had arrived here.”