Infectious disease specialists believe it is time for Canada to emulate other industrialized countries and establish a national vaccination registry.

There is an increase in measles cases this year, with 131 so far this year, compared to just 12 in 2023. This includes a recent outbreak of 50 cases of measles in New Brunswick, and one fatal case for a child under 5 years old in Hamilton, Ontario.

Since measles is one of the most contagious infectious diseases, and can cause serious long-term sequelae, vaccination is recommended to neutralize it.

Why a register?

The Dre Joanne Langleyspecialist in infectious diseases in children at the Science Center IWK of Halifax, Nova Scotia, thinks it’s time for Canada to create a national immunization registry.

She said it would be an excellent tool for reducing cases of measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases.

Open in full screen mode

Dr. Joanne Langley, infectious disease specialist and pediatrician, during a webcam interview in May 2020.

Photo : -

It would also allow health professionals and public health officials to compile relevant data on vaccination coverage, vaccine safety, and the effectiveness of immunization efforts against preventable diseases.

For adults, it would also be simpler to consult an immunization file which contains information on vaccines received at a very young age, notes the epidemiologist Tim Slyprofessor emeritus at the School of Occupational and Public Health at Metropolitan Toronto University.

In Canada, he said, we dig through the kitchen drawers to find a small notebook

which contains information about vaccines received decades earlier, sometimes in a different province.

In the age of information technology, we must have a national database

he says.

Open in full screen mode

A vaccination card with a blue cover from the Quebec government. The yellow document is an international vaccination certificate issued by Canada as proof of vaccination for travelers. (Archive photo)

Photo : Ivanoh Demers

Several European countries have such a system. Canada is behind other countries, thinks the Dr Sly and the Dre Langley. The latter points out that the idea was raised during a previous measles outbreak in New Brunswick, in 2019.

With a reproduction rate (R0) of 15, at least 94% of the population must be immunized to prevent the transmission of measles, according to the Canadian Immunization Guide (New window).

In Canada, we left [ce taux] go down to 80%, and that’s why we’re going to see more outbreaks

warns the Dr Tim Sly.

In New Brunswick, for example, data from the Department of Education indicates that only 71.8% of children who entered kindergarten at the end of 2023 were vaccinated against all nine diseases (whooping cough, diphtheria, meningococcal disease, mumps, polio, measles, rubella, tetanus, chickenpox) for which the province requires proof of immunization.

After COVID, no political will

Open in full screen mode

According to the director general of the Canadian Public Health Association (absent from the photo), there is no political will in Ottawa to create a national registry. (Archive photo)

Photo: The Canadian Press / Sean Kilpatrick

The creation of a national vaccination register is a crucial first step to saving our health care system

affirms Ian Culbertthe executive director of the Canadian Public Health Association, a non-governmental organization.

The simplest and most financially sensible thing is to prevent these diseases. Vaccines give us the power to do this

he emphasizes.

Without a national registry, or even provincial registries, we cannot target our efforts to accelerate immunization in underimmunized communities

he adds.

According to Ian Culbertthere is no political will

to create a national registry for all recommended vaccines.

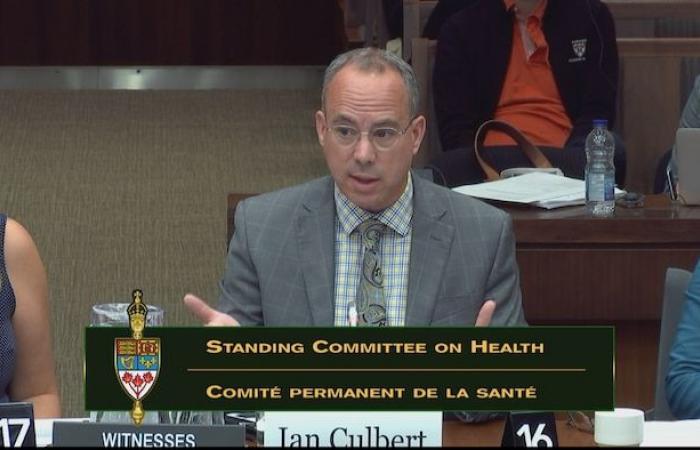

Open in full screen mode

Ian Culbert, director of the Canadian Public Health Association, before the standing committee on health in 2018 in Ottawa.

Photo : - / CBC News

Governments appear to him much more interested

to invest in hospital care as well as in public health.

He believes hostile reactions to temporary COVID-19 vaccination requirements and public health measures early in the pandemic made governments hesitant.

Open in full screen mode

The Pontifical Swiss Guard checks proof of COVID-19 vaccination of tourists arriving at the Vatican, October 1, 2021.

Photo : Associated Press / Andrew Medichini

A national registry would not be that complicated to create, argues Ian Culbertas each province and territory managed to quickly set up its COVID-19 vaccine registry.

Not so simple, according to the Public Health Agency

Nicholas Janveau, spokesperson for the Public Health Agency of Canada, offers a contrary opinion. A national registry, he says, would face a number of obstacles anchored in the structural, legal and operational realities of our health care system

.

A centralized system would also present an increased risk of security breaches because of the concentration of personal health information

he says.

Open in full screen mode

The first dose of a measles vaccine is usually given to children aged 12 months, and the second dose at 18 months or between 4 and 6 years old, according to Health Canada. (Archive photo)

Photo: Reuters / Valentyn Ogirenko

Health care, including vaccinations, is under provincial jurisdiction. There is no law in Canada that authorizes the federal government to require health care providers to document inoculations and report them to a centralized system.

Incomplete data would reduce the reliability or usefulness of a national registry, says Nicholas Janveau. An approach according to him more pragmatic

would rather be to improve the sharing of information between each province.

This work is underway, he says, encouraged by the success of joint efforts to combat COVID-19.

According to the report of Bobbi-Jean MacKinnon, CBC