To understand how a cancer develops, researchers are trying to observe its progression, cell by cell. In a series of no less than 12 articles published on October 30, several teams published part of the data that they have so far drawn from a real “atlas” of cancers.

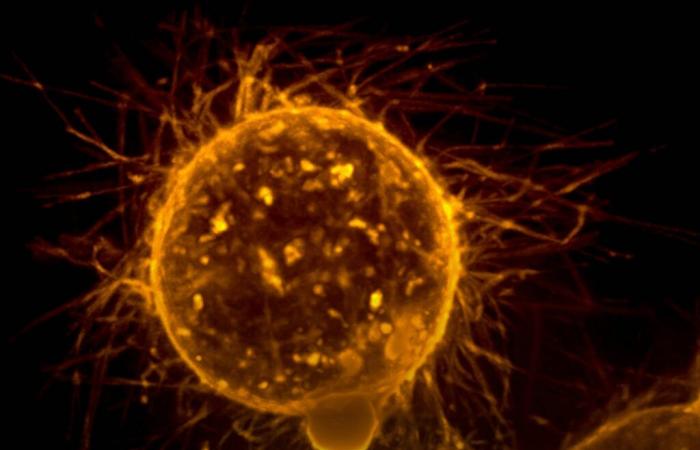

The 3D maps in question, 14 in number for the moment, are produced from the analysis of human and animal tissues. And they are precise enough to pinpoint the position of each cell making up a tumor.

The ultimate goal, the researchers write, is to better understand the mechanisms that, at the microscopic level, govern the progression of a tumor. As well as the reasons why not all clusters of cancer cells respond to the same treatments in the same way.

The project, called the Human Tumor Atlas Network, which has been under the wing of the US National Cancer Institute since 2018, analyzed more than 8,000 “biospecimens”—for example, cancerous tissue taken from a human or a animal—representing more than 2000 cases of cancer. Half are breast cancers, the others are divided between lung, colorectal, pancreatic cancers and around fifteen others.

Some of the 12 studies published on October 30 describe the “maps” of cells. Others identify the progression of mutations in the cell’s genetic material that lead to cancer—and more specifically, the rate at which these mutations occur, what some experts call the molecular clock. One hypothesis is that treatments could precisely target a moment in this progression that has been identified as a key stage in the development of a tumor.

By observing everything cell by cell, researchers return to information known to oncologists for a long time: even within a tumor, not all cells are cancerous. Consequently, a treatment which would succeed in distinguishing one from the other would be all the more effective, we hope: this is the principle of immunotherapy, which is to “train” the immune system to recognize the cancer cells and destroy only them.