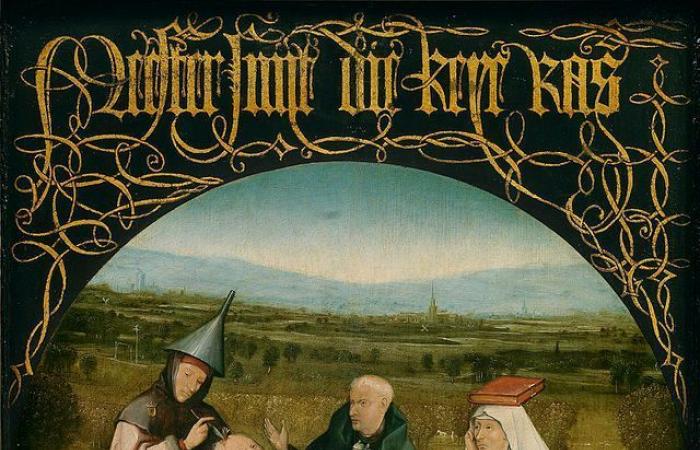

Who is this madman, who can be seen in the painting by Hieronymus Bosch, Lithotomy, featured in the exhibition Figures of the fool. From the Middle Ages to the Romantics, which is being held until February 3 at the Louvre Museum in Paris? He is surrounded by many others, smiling, dancing, grimacing but above all looking, looking at us. One pretends not to see by hiding his face with his hand with outstretched fingers, the others put on thick glasses to blind themselves in the light of useless books. And what else are we doing, not seeing this bad wind coming, the time of the world’s madness? “ Mad about himself, his eye on his image, and without even realizing that he sees a madman in his mirror ”, we can read in the Ship of Fools by Sebastien Brant, in 1494. And this is what we will no longer read quite like in thePraise of madness by Erasmus in 1511. Hieronymus Bosch painted in this uncertain meantime. So obviously it looks at us, in this big mirror.

So let’s take a look, with: Michel Weemansprofessor of art history at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, specialist in Flemish art, and in particular its landscapes, the tricks and fables of which he studies. He signed the chapter on Bosch and Bruegel in the catalog Figures of the fool. By his side, Maud Pérez-Simonlecturer in medieval literature at the Sorbonne Nouvelle University, who is a specialist in the relationship between text and image. She published at Champion, with Pierre-Olivier Dittmar, a curious text from the 13th century, The monsters of men. Both are joined by François Chaignauddancer, choreographer and singer, who presents a performance entitled Little players, alongside the Louvre exhibition, until November 16 (continuous from 7:30 p.m. to 11:30 p.m.), as part of the Autumn Festival.

From the incongruous to the universal

Lithotomy by Hieronymus Bosch is an oil on oak of fairly small dimensions (48 by 34 cm), kept at the Prado Museum in Madrid. This painting was part of the collections of Philippe de Bourgogne before 1524. It is also given the title “Excision of the stone of madness”, a practice that has long been believed to be carried out by certain surgeons from the Middle Ages or the beginning of the 16th century, but this is not historically attested. Lithotomy is in reality only a visual motif to express the credulity of those who submit to the charlatanism of surgeons. As Michel Weemans explains to us, although Hieronymus Bosch was not able to witness this operation, he was nevertheless linked to rhetoricians whose plays depicted charlatans in the process of removing the stone of madness. .

In any case, it would be very difficult to read this work literally since the scene painted by Hieronymus Bosch takes place not indoors, but outdoors, unlike other later scenes which will be inspired by this painting. According to Michel Weemans, anchoring the operation in the middle of a vast landscape, with a very luminous horizon, is an incongruity which immediately leads us to understand that we should not take it seriously. The historian also believes that the landscape within which Bosch chose to place the scene is, due to its circular composition, a “world landscape”, a way of symbolizing its universality. It should also be noted that the circular shape of the work resembles a speculum or a mirror, like other paintings by Hieronymus Bosch. We are meant to recognize ourselves or our distorted reflection in this painting.

Mathieu Potte-Bonneville’s Postcard: turning your head, with “The Fool on the Hill” by the Beatles

During the show, we have the joy of receiving a postcard from the philosopher and director of the Culture and Creation department of the Center Pompidou, Mathieu Potte-Bonneville. For once, today’s missive is musical – because yes, songs can also be images, especially when they turn on themselves and repeat three or four times with the same motif. This is how it is The Fool on the Hill by the Beatles, dated 1967. Excerpt:

“The Fool on the Hill presents such an obvious structure that when he composed it on the piano Paul McCartney dispensed with putting it down on paper, believing he would have no difficulty in remembering it, “in his head” as they say. Precisely, he paints there, in a voice of the head, the picture of someone who does not have all his head, a picture of which we contemplate in turn the obverse and the reverse: tails, the man is seen from the outside (“they can see he’s just a fool”), face, he is seen from the inside; tails, we evoke the face he has, and tails we are in his head; or rather, because it is a complicated symmetry where inside and outside stand head to tail, tails, we describe the passers-by who pass the madman without ceasing for an instant to be completely inside themselves, without seeing anything or hear or want to know anything about him; and opposite, from within, it is the outside that we see, nothing less than the cosmos, because (I quote) “the eyes in one’s head see the world turning”. Thus, from the top of his hill, the madman stands up to those who see him without seeing him, without seeing that he is seer.” Mathieu Potte-Bonneville

To view this Youtube content, you must accept cookies Advertisement.

These cookies allow our partners to offer you personalized advertising and content based on your browsing, your profile and your interests.

Manage my choices I authorize