Discounts are everywhere, all the time, when you buy online, so much so that you wonder if the regular price isn’t an illusion. The trend reaches its limits on the pages of “influencers”, deal masters who relay deals that are not deals.

• Also read: Sale of our data: Canada Post pleads immunity, judge refuses

• Also read: Sending Quebec is eating into Amazon, slowly but surely

“New Facebook or TikTok accounts appear every day,” observes a Quebec expert on the subject, Julien Gaudelin, founder of the guide specializing in online shopping BuyLeMeilleur.ca.

With names like “Noémie’s Best Discounts” or “Best Amazin Deals Canada,” these pages claim to offer 20, 30 or 40% off products like a Bluetooth speaker or a non-stick frying pan.

This page offers misleading discounts, according to Julien Gaudelin’s methodology.

screenshot of the Facebook page “Noémie’s best discounts”

Every day, a continuous stream of patents and tools appear on the screens of customers, sorry, Internet users. Every time “Place Order” is clicked – often on Amazon – the influencer-hunter behind the sale gets money, their cut you deal.

Some pages, like The Deal League, do their job well, adds Julien Gaudelin, who insists that not all deal hunters are deceptive.

“The success of some motivates others to copy and paste the recipe, but without checking the discounts,” observes someone who knows how to recognize a bargain.

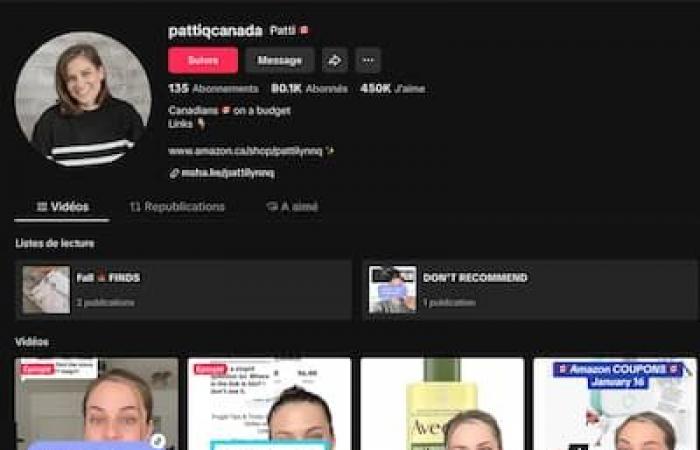

The TikTok account @pattiqcanada does not offer authentic discounts, according to Julien Gaudelin’s methodology.

screenshot of TikTok account @pattiqcanada

70% fake discount

Thanks to his free tool The Filter, which tracks the price evolution of thousands of products, Julien Gaudelin calculated, last summer, that seven out of ten discounts are misleading on the pages of influencer-hunters.

With his team, he sifted through 1,450 discounts taken from 29 popular pages. Fifty posts from each of these pages with all more than 3,500 followers were analyzed.

Misleading deals are those displayed at a price higher than the lowest price observed over the last 90 days and/or those which do not specify the price of the product over the last three, six or twelve months.

-Enjoy the world

Julien Gaudelin is also in the deal business, his site is profitable thanks to the income earned from the offers he publishes.

Some pages only repeat content from the Amazon Offers Store, he laments.

“They are taking advantage of the crazy bargains, not everyone is honest,” summarizes the expert.

False discounts, according to the law

It is prohibited to advertise a good or service at a reduced price if it is false, says the Consumer Protection Act (LPC). A merchant can only display a discount if the product has been displayed at full price within 30 days prior. That’s for the stores. Because online, “it’s more vague,” notes HEC marketing professor Jean-François Ouellet. “A foreign company that sells online does not quite have the same standards that apply,” he summarizes.

-60% everywhere: the madness of deals

In the wonderful world of online shopping, the crux of the matter is that the customer does not leave their basket full without purchasing anything.

“At least 70 to 80% of shopping carts are abandoned,” illustrates HEC marketing professor Jean-François Ouellet. Walmart, like the local SME, is experiencing this issue.

To speed up the pace between the “Add to cart” click and the “I buy” click, retailers are banking on the base instincts of the consumer-Internet user.

“The discount is a good weapon, it encourages us to make impulsive purchases, it makes us experience FOMO – fear of missing out –, like when it disappears in five minutes or less,” illustrates the consumer behavior specialist.

In stores, retailers take margins of 40 to 60% per sale in order to cover rent, salaries, and so on. Online, margins may be smaller.

“When you just have a warehouse to manage, you go for it,” laughs Ouellet about the discounts that we find everywhere.

All businesses do it, from the biggest to the smallest, because to maintain your market share, you have to run as fast as your competitor.

“It’s the Red Queen theory. If everyone does the same thing, you have no choice, whether you want it or not,” summarizes the professor.

Online marketers know very well that a consumer who has purchased once impulsively has a good chance of doing so again.

“They know it more and more precisely. Welcome to 2025,” he emphasizes, before mentioning “the many AI start-ups” specializing in the field in Montreal.