Making difficult decisions in times of crisis: can Europe meet the challenge?

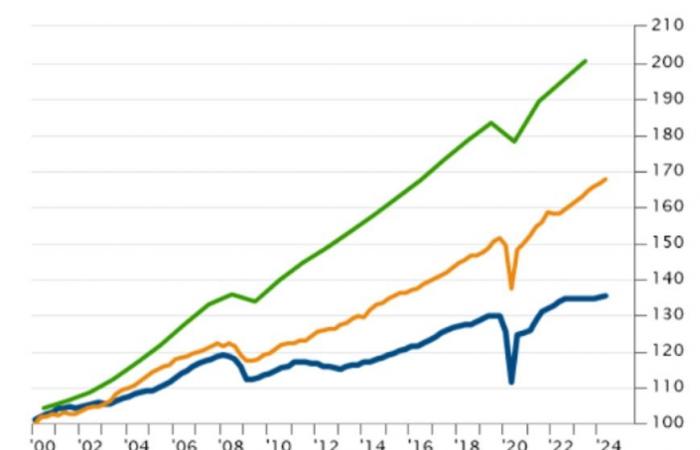

Eurozone GDP grew modestly by 0.4% in the third quarter, beating forecasts of 0.2%. Although this slight rebound is encouraging, it remains to be seen whether it can compensate for the persistent economic stagnation observed over the past two years. Since the end of the post-pandemic fiscal boost, growth in Europe has been anemic, with GDP barely growing since the third quarter of 2022. Several headwinds have slowed the eurozone: disruptions in energy supplies, weak Chinese demand, restrictive monetary policy and declining budgetary support. But above all, it is structural weaknesses that are holding Europe back, and have been for more than twenty years.

In this context, Mario Draghi’s report published in September, entitled “The future of European competitiveness”, marks a turning point for the continent’s economic policies. This report reveals the causes of the slowdown in growth and proposes necessary actions to prevent Europe from a “slow agony”. Europe must grow faster, not only to counter recent economic difficulties, but also to secure its place in a changing global economic order.

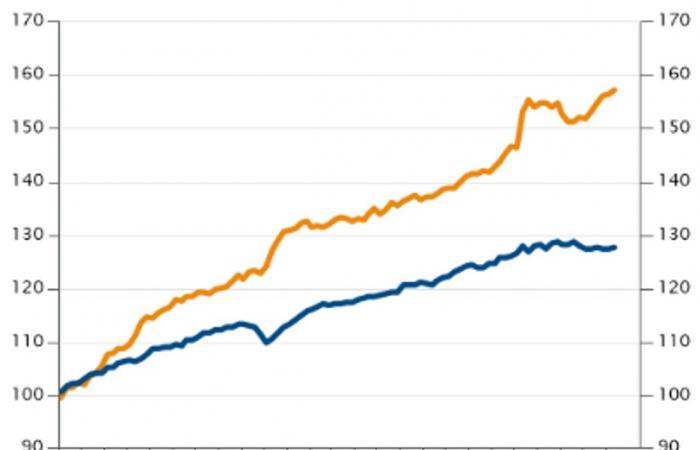

Short-term recession risks

Source: You

Mario Draghi’s report was published at a time when the euro zone is experiencing a new episode of economic weakness. After a near-recession in 2023, growth resumed at the beginning of 2024 thanks to an increase in household consumption and exports. Unfortunately, this encouraging dynamic quickly lost momentum, and the +0.2% GDP growth recorded in the second quarter was mainly due to exports and public spending, while private consumption stagnated and business investment was retreating.

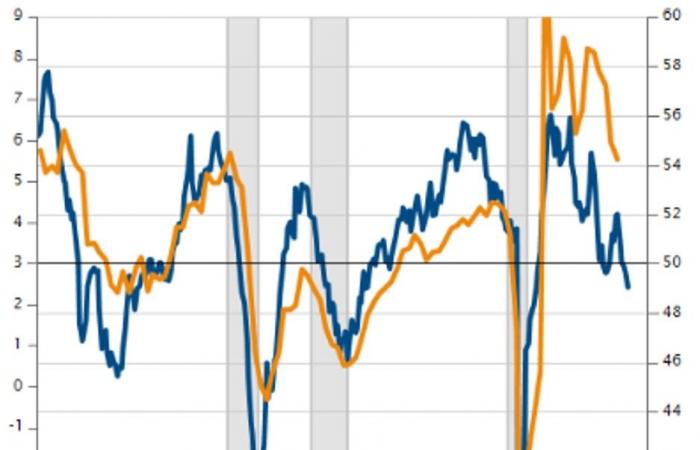

This slowdown appears to have continued into the summer, which does not bode well for GDP growth in the second half. Most economic indicators have disappointed and deteriorated recently, signaling, at best, anemic growth for the eurozone as a whole. In September, the PMI Composite index fell below the expansion threshold, and remained in the “contraction zone” in October. Germany is under particular pressure, with its industrial contraction since 2023 weighing on the entire economy. Unemployment rose from 5% in 2022 to 6%, and consumer confidence and consumption remain sluggish, with no signs of improvement.

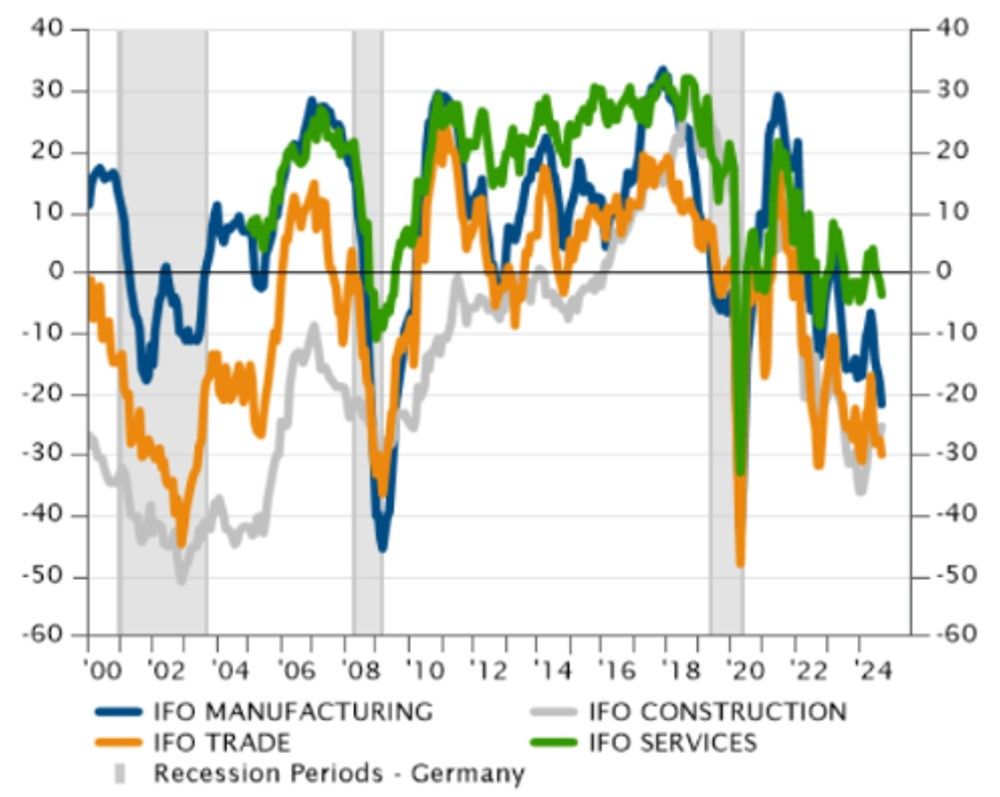

Source: You

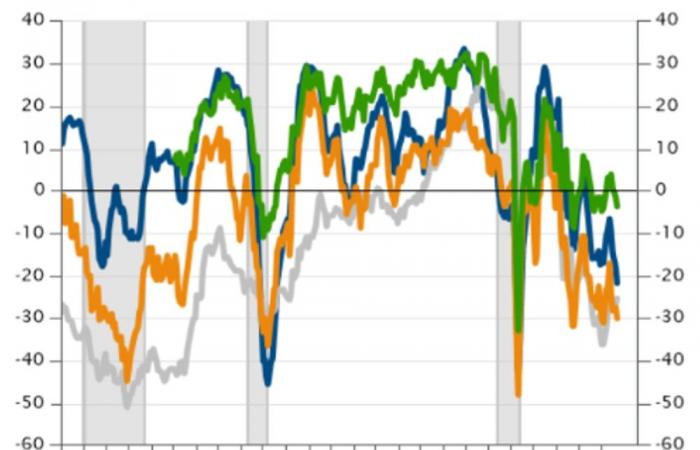

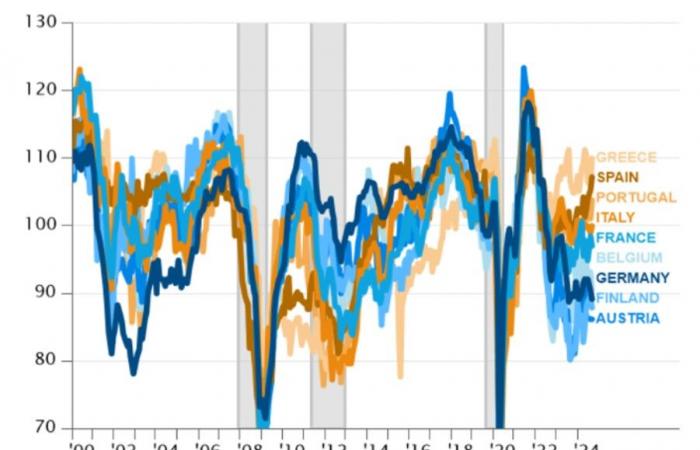

Since 2022, Europe has suffered a succession of unfavorable shocks: sanctions against Russia after the invasion of Ukraine, the disruption of Russian gas supplies, the slowdown in Chinese demand for manufactured goods, a surge inflation and a marked increase in interest rates. However, Germany was the most affected, due to the structure of its economy.

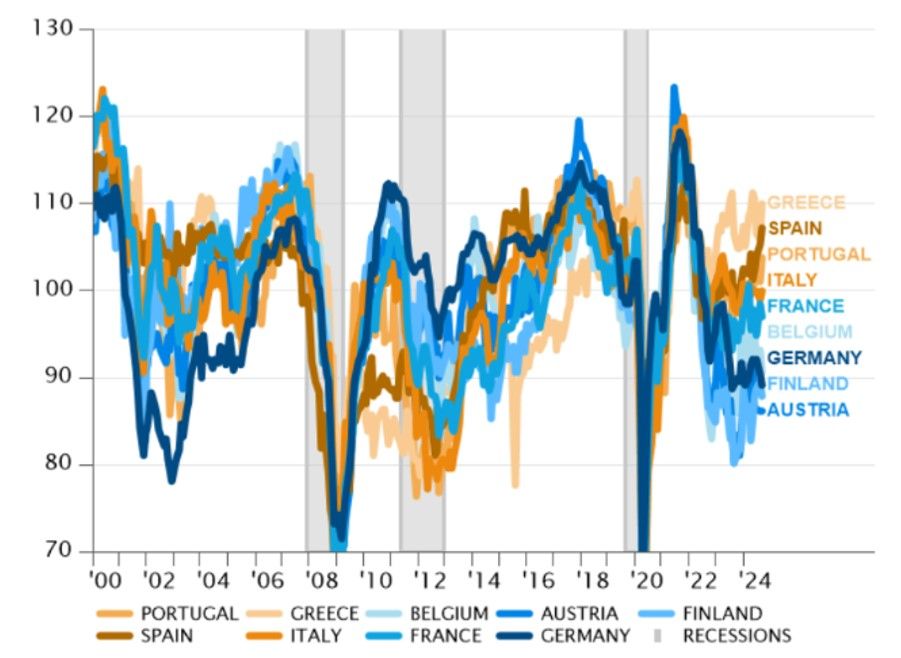

Conversely, southern European economies have been relatively spared from these recent difficulties, benefiting from resilient demand for services, particularly in tourism. In 2024, their growth and economic morale were on an upward trend, a marked reversal from a decade ago, when “peripheral” economies were plunged into deep recessions while “core” economies drove growth. European.

Source: You

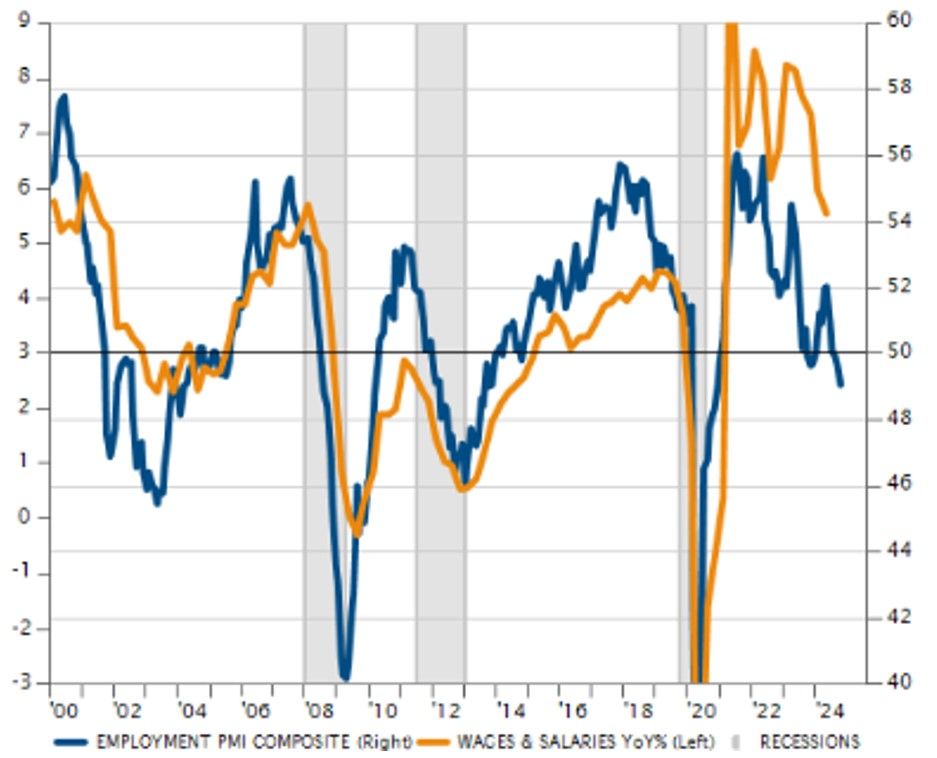

Employment trends also reflect these divergent dynamics in Europe. Unemployment in the eurozone has stabilized at a historically low level of 6.5%, but it has increased in Germany and France, while it continues to fall in Italy and Spain to levels not seen since 2008 However, signs of more widespread weakness in the labor market are emerging, with the PMI employment index contracting for a third consecutive month in October. This slowdown could further weaken domestic consumption, increasing the risk of a contraction in demand that could push the euro zone into recession.

The deterioration in the job market, however, eases the ECB’s fears about inflation, thus allowing an acceleration of monetary easing with a further rate cut this month. The European economic slowdown should ease inflationary pressures, thus raising questions about the restrictive nature of the ECB’s policy. Tight credit standards and weak private credit growth are also weighing on Europe’s growth prospects.

Source: You

Thus, current economic trends remain unfavorable for the euro zone as a whole, despite the dynamism observed in the south of the monetary union. The northern part is already in recession, or approaching it, and the risk of a weakening of domestic demand in the coming months is very real. New challenges in 2025, such as budget restrictions in France and Italy, US tariffs and trade tensions with China, could worsen the situation. Although ECB easing could support interest rate-sensitive sectors as well as household consumption, it is unlikely to be enough to reverse Europe’s economic stagnation.

Long-term risks of a “slow agony”

In September, former ECB President Mario Draghi published The Future of European Competitiveness, a landmark report on EU economic policy. After an uncompromising analysis of the economic situation in the European Union, Draghi proposes a series of recommendations and policies to be implemented to promote sustainable growth in Europe and avoid a “slow agony” for the world’s second largest economy.

Source: You

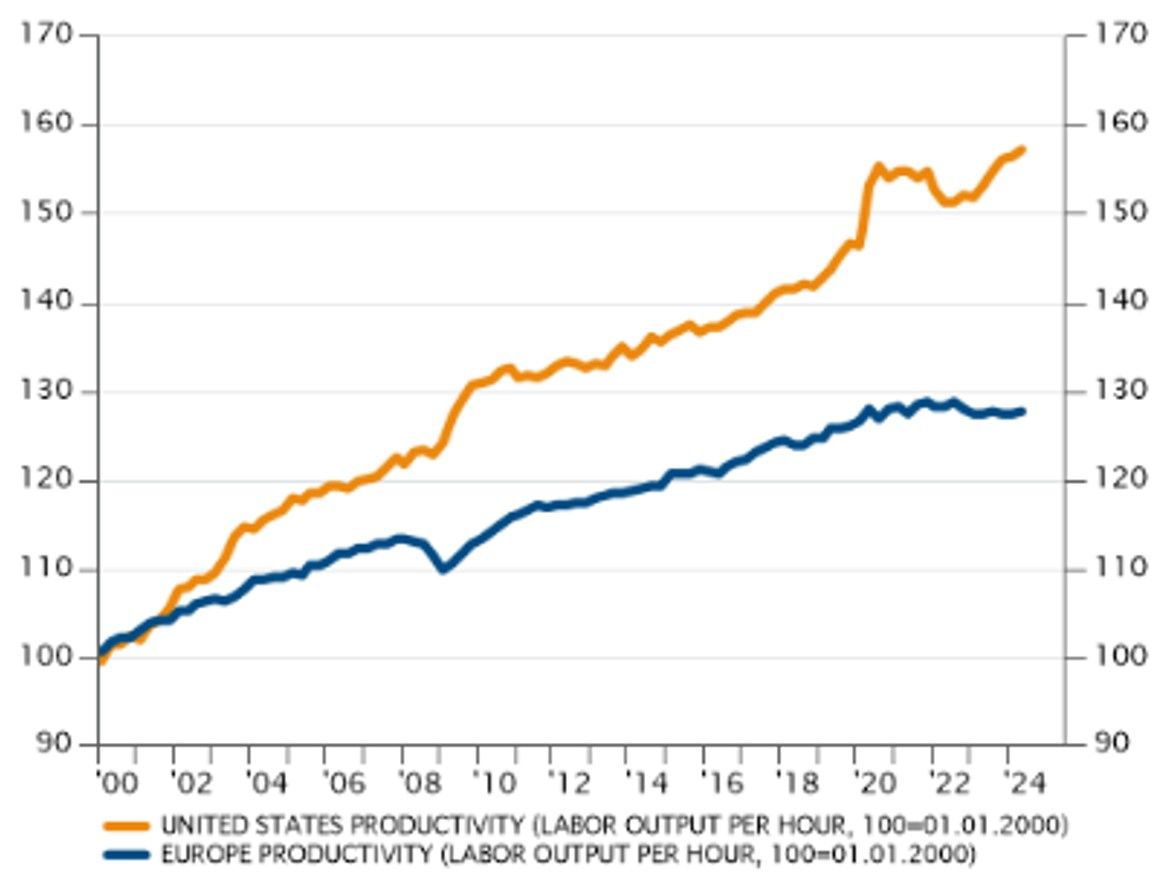

Draghi’s words are so clear that they can simply be quoted: “Europe’s need for growth is increasing. The EU is entering the first period in its recent history where growth will not be supported by population growth. By 2040, the workforce is expected to shrink by nearly 2 million workers each year. We will have to rely more on productivity to stimulate growth. If the EU were to maintain its average rate of productivity growth since 2015, this would only be enough to keep GDP constant until 2050, at a time when the EU faces a series of new investment needs which will have to be financed by higher growth. To digitalize and decarbonize the economy and increase our defense capacity, the share of investment in Europe will need to increase by around 5 percentage points of GDP to levels not seen since the 1960s and 1970s. This is unprecedented.”

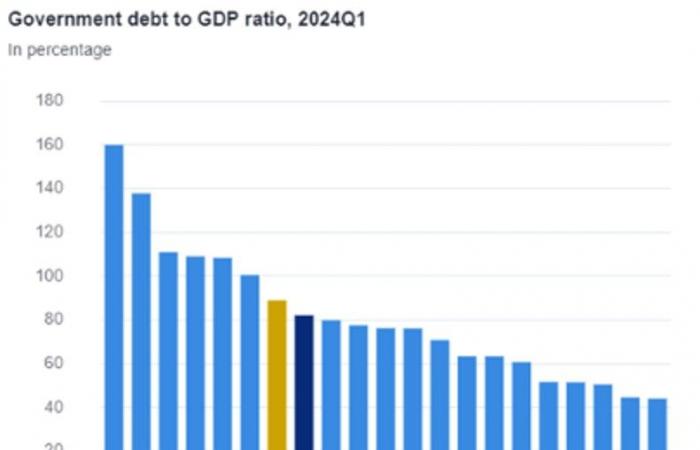

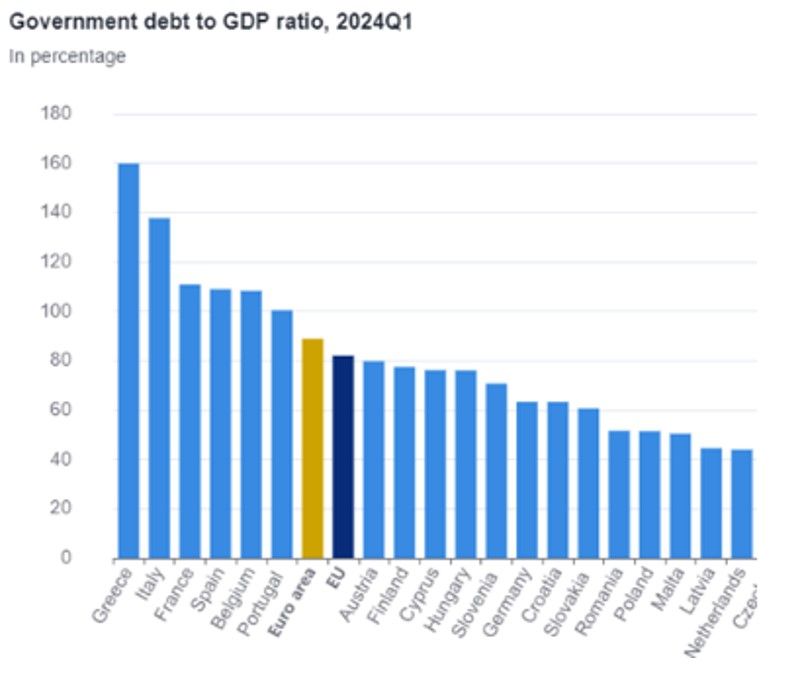

5% of EU GDP equates to more than €800 billion in annual investments, requiring public and private financing. With public debt exceeding 100% of GDP in most major EU economies (except Germany), increasing debt to finance these investments may seem counterintuitive. Yet the report suggests that if these investments boost productivity and growth, they could ultimately strengthen public finances by expanding fiscal capacity.

Source: You

Draghi’s report identifies three areas for action to revive sustainable growth in Europe:

- Closing the innovation gap with the United States and China, particularly in advanced technologies.

- Develop a joint and coherent plan for decarbonization and competitiveness to transform this necessity into an opportunity rather than an obstacle to growth.

- Increasing security and reducing dependencies in a context of growing geopolitical risks.

The richness of this 328-page report lies in its ability to transparently and comprehensively expose Europe’s economic situation, the worrying prospects if no action is taken, as well as the actions needed to change course. European leaders now face a decisive choice: follow these recommendations or ignore them. Although the process may be lengthy, many of Draghi’s proposals could quickly promote growth. The November 8 meeting of EU leaders in Budapest represents an opportunity to act, although the political climate in Europe makes this task more difficult than ever.

Making difficult decisions in times of crisis

Draghi’s report on European competitiveness comes at a crucial time: with post-Covid effects fading and growth declining, urgent action is needed before new global trade challenges emerge. This report also comes at a politically delicate time, as Draghi’s recommendations require European countries to cooperate and make collective decisions that will improve common growth prospects in the medium term, in contrast to the current focus on national concerns in the short term. term.

In this regard, two reactions from the German Finance Minister highlighted the difficulty of the task facing Europe: less than three hours after the publication of the Draghi report, Christian Lindner clearly rejected the idea of a common loan at European level: “Germany will not agree to this.” A few weeks later, he would have warned his Italian counterpart against a possible takeover of Commerzbank by Unicredit. These statements can hardly be interpreted as signs of enthusiasm on the part of Europe’s largest economy for greater economic integration and cooperation.

More generally, recent European elections have revealed growing support for anti-establishment parties, reflecting waning enthusiasm for a unified Europe. France faces political paralysis, pro-European parties have lost ground, and Germany’s governing coalition is weakening with each regional election, as parties focus on next year’s federal elections. Anecdotally (or not), Germany’s decision to unilaterally reestablish border controls was a telling example of the currently limited appetite for European cooperation. Moreover, the last European Council held this month focused on migration issues and geopolitical discussions regarding Ukraine and the Middle East, leaving little room for the worrying economic situation internally.

In this context, Draghi’s report highlights that there are solutions to improve the European economy, but they require political will. While ECB easing and a recovery in China may offer temporary relief, it is up to European leaders to make choices. Their response will determine whether the report becomes a wake-up call or a missed opportunity to save the European economy.

Conclusion

The United States experienced its Bidenomics, which spurred investment in infrastructure and new factories while supporting consumption through extended welfare benefits and household tax cuts. China has just announced a vast recovery plan which has so far focused on supply-side policies, aimed at facilitating access to credit and slowing down the fall in the real estate market, but which could soon be supplemented by measures targeted at households to reinvigorate consumption. Europe is the major economic zone which is lagging the furthest, constrained by fragmented national budgets.

Individually, Europe’s major economies do not have room to provide short-term fiscal stimulus. The only way to achieve a form of fiscal stimulus in Europe would therefore be to reach an agreement on the implementation of the Draghi report strategy, financed by special debt issued at European level. The November 8 meeting in Budapest represents a key opportunity for European leaders to commit to a unified economic strategy. The stakes are high: can Europe meet the challenge?