Born on October 9, 1939 in Berchem-Sainte-Agathe, the writer was a doctor of law, specialist in international law and director of the Center for the Sociology of Literature at the Free University of Brussels. He began publishing novels and short stories in 1969. We owe him, among other things, Good offices (Seuil, 1974) and Land of Asylum (Grasset, 1978) but it was in 1987 that he received the Médicis prize for The Dazzles.

In 1989, he was elected a member of the Royal Academy of French Language and Literature of Belgium and named Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters of the French Republic. In 2009, he received the Prince-Pierre-de-Monaco prize for all of his work.

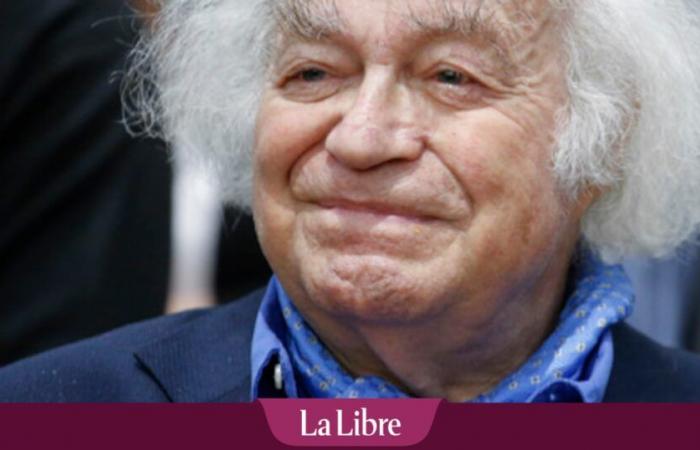

Born to a resistant father and a Jewish mother, he was a “hidden child” during the Second World War and never spoke about it until he was seventy. Jean-Pierre Orban also evokes this page of his history in The century for memory, a masterful and fascinating biography, published in 2018, which traces his life and work. We found Pierre Mertens at the time to discuss the power of literature and the ambiguities of a life in his “mirador” on the 11th floor at the top of Boitsfort, in front of the forest, surrounded by a landscape of dunes of piled up books everywhere…. He then seemed, at his 79 years old, torn between the pleasure of such a strong biography, never hagiographic, and embarrassment in the face of the reported details, sometimes more intimate, of the life of a man and those close to him. A writer who has always mixed his life with his novels and who asks questions about the ethical limits of literature.

Landscape without Pierre Mertens

Without doubt, he relived the experience that Freud had one day on a train, seeing a man he did not know arrive, before realizing that it was his reflection in a mirror.

All your work is a construction of yourself which involves your loved ones, your friends, your children and even the history of the world. But Orban shows that it could have bullied some people to find themselves in your writings?

Overall, they are satisfied and do not feel betrayed.

Thought comes through writing. Is it the work that speaks?

Montaigne said:My book did more to me than I did my book.” All my books form my real life. If life were perfect, I wouldn’t write. I once said that I was adding a pagan codicil to New Testamenta way of expressing what I have as a believer, because I could not define myself as a non-believer. God ? I don’t know if I believe it, but I think about it. I am, in reality, in dialogue all the time, in the “you” and not in the “I”. We often write to say what we think, but, in the novel, it goes further: we write to discover what we did not know that we thought, we write what we do not know that we will find out. Like Columbus, who left for India and discovered America, and even invented it. It is not for nothing that my first novel was titled India or America.

On the wall you have a photo of a magnificent self-portrait by Rembrandt.

It’s chiaroscuro. Each time Rembrandt “reproduces” himself, he is other. I believe in the truth, but also in the opacity of the truth.

Your childhood experience was essential, Orban emphasizes…

When I started writing, I only wanted to write one book that would tell the story of this childhood as a child who was hidden because he was Jewish. It was never explained to me what was happening, I was surrounded by mysteries. By chance, I was born the day Hitler decided to invade Belgium. I could believe that the war would last forever.

-I always wanted to keep my childish outlook. Baudelaire said:Genius is only childhood clearly formulated.” Georges Bataille said that Kafka practiced “perfect childishness” and you know my admiration for Kafka, of whom we see so many photos in my apartment. Sartre and Camus are adults, while Kafka keeps the questions of childhood. I didn’t write novels about learning, but about unlearning. Learning is the concealment of the truth. Dostoyevsky, Proust, Kafka are more committed in this sense than Sartre or Camus. What could be more committed than Flaubert writing Madame Bovaryplanting a bomb in the society of his time, which earned him a trial. Pasolini, the most committed intellectual of the 20th century, because he threw his body into the struggle, once told me that the proof of commitment is the trials. He had more than thirty.

You had two. One of Princess Liliane for “A Royal Peace” and the other from Bart De Wever for having described him as a “denialist”.

I had no pleasure in undergoing this great suffering of seeing a book transported from the literary chronicle to the legal chronicle.

Women were a constant in your existence, always associated with the stages of your life and your work, as Jean-Pierre Orban shows.

A writer said he wrote for women. Freud speaks of it as a “dark continent”but which we so want to explore. One of my biggest fights has always been against domestic violence against women. My love of women, my fascination with her, has always been accompanied by this fight. I qualified”of a lesbian man”.

Another of your current battles is anti-Semitism. We talked about a shift in your vision of the Palestinian question.

We must never avoid fighting. Like Nabokov, I think he “It takes as little as it takes to make the Brute back down.”. The galloping resurgence of anti-Semitism frightens me terribly. No, I didn’t take a turn. From the start, I avoided any Manichaeism, always advocating the two-state solution, like Amos Oz and David Grossman.

Do you continue to write?

I have no choice, I can’t help it. It’s my double life: my life is my legitimate wife, but writing is my mistress. Jean-Pierre Orban unearthed a never-finished manuscript from my archives The American novel. I am working on it again as on the text of an unknown person and it will henceforth be titled The simplest expression. I am also preparing a literary tribute to the life of Véronique Pirotton, not on her tragic death (Bernard Westphael was suspected of murder, then acquitted with the benefit of the doubt), but on a living woman who loved life more than life did. loved.

Do you fear death?

I never liked these philosophers repeating that death is part of life. No, it remains absolute nonsense, an absurdity. Only voluntary death would have meaning. But I cannot resist the temptation not to commit suicide, because I can still live, love, write. In certain respects, my emotional and intellectual lives, which have always gone hand in hand, have never been so fruitful and I feel younger than at 20, when I see again the young man that I was, as already a young old man. Today I face more mysteries. The secret ends up winning out and it is the role of the novelist to ask more questions than to provide answers.