Since 2021, Fiona Mille has voluntarily chaired the mountain preservation association Mountain Wilderness France. Furthermore, a consultant in territorial resilience and manager of a gîte in Belledonne, she has just published Let's reinvent the mountain. Alps 2030: another future is possible published by Faubourg. This resolutely optimistic essay invites dialogue and reveals a range of new perspectives for the mountains. Interview.

Fiona Mille near Lake Freydières, place of inspiration for writing her book © Capucine Veuillet

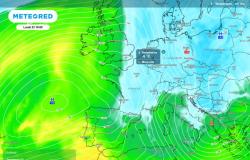

It was the announcement of the Winter Olympic Games in the Alps in 2030. I really had the feeling of a world moving at two speeds. My daily life is meeting people who are active on transition issues. For three years, I have observed an acceleration of awareness in all circles, especially economic but also political and civic. There is a lot of desire to try to do things differently. At the same time, the acceleration of climate change is striking. So I perceived the announcement of these Games as a brake: we are talking about transition, about changing our ways of living and these Games, for me, are about celebrating only winter sports, it is about look to the past rather than the future.

Do you think that the time should no longer be for observation but for projection?

Yes, and that’s what I wanted to do with this book. When we talk about transition, we might think that it is only about reconciling wild mountains and mountains to live in, that it is a question of knowing how to live while respecting planetary limits. Of course, it is part of the DNA of Mountain Wilderness but since the States General of the transition of mountain tourism, which took place in 2021, the challenge is to sit around the table, to discuss, to leave of a common observation to project ourselves together. However, I find that today, we are making the observation but we are unable to project ourselves into the future with lucidity and desire. That is to say, some people plan ahead but turn a blind eye to the real issues or emphasize the fact that the future can be complicated without remembering that it can also be fun. It is this balance that must be found. This is what my book is about.

© Capucine Veuillet

Is this desirable future supported or on the contrary compromised by the 2030 Winter Olympics?

This is not a book about the Winter Games. It's a book about the mountains, about the mountains, with the Winter Games as a gateway because this event is a reflection of the vision that we want to have on our mountain territories. The Games are structuring, they are supported by a strong public policy and are an opportunity to highlight our territories. In the book, I consider three scenarios for the mountains. In the first, the Winter Games are held with a policy of “whatever it costs”. This is a bit like the trajectory we are taking: we are more and more above ground, we are afraid of the future but we are attached to it in a relationship that I find quite artificial in the mountains. In this scenario, I therefore question the limits of our use of artificial snow, those of the development of mountain territories, of the belief in a technology which will allow us to continue. I am developing the headlong rush, in a scenario where it is money that guides us, leading to the move upmarket of territories. Actors are moving in this direction and I still wanted to make it visible. It's not science fiction, it's really foresight nourished by real elements.

The second scenario seems more optimistic but it is nevertheless the scariest…

This is the scenario in which the Games are not held and it is really the one that I do not want to see happen because it describes a world where we take the trajectory of +4°C on the scale planetary. A world in which scientists agree that humans cannot adapt. In this scenario, the acceleration of climate change is such that the Games are no longer even relevant. We have to manage questions around the problem of water resources, around mobility… At this stage, the Games can no longer even take place, they seem futile to us. Then comes the last scenario, the one that questions our priorities.

Today, the Games are about to take place and I don't want to put all my energy into being anti-Olympics. In this chapter, I therefore wonder what is essential. The issues of water resources, food resilience, reducing our dependence on cars in the mountains: all of that seems a priority to me. And it's too easy to forget it and say to yourself: “Come on, let’s put our energy elsewhere”.

“We can have deep disagreements on the vision of the mountain but deep down, we are on the same boat. »

Ecology is often criticized for being pessimistic and undesirable. Are you attached to the party, to formulating joyful perspectives?

That's what gets me. This last chapter of the book is not a utopian perspective: it is probable that the Winter Games will take place because there was no reason to stop them, but that we decided to put the energy elsewhere. There are dynamics in the territories, collectives and I imagine them carrying out another mountain festival in 2030. A sporting festival where we adapt to the mountains rather than the opposite, where we accompany the citizen momentum. What could it look like? What impact would this have on the economy, hospitality, agriculture, housing? I show that not everything has to be invented. We are not starting from a blank page: there are plenty of things that already exist. We must now find how to highlight them, how to support them.

You mentioned earlier the Estates General for the transition of mountain tourism, which took place in 2021. Did they serve any purpose? What is the outcome of Mountain Wilderness today?

For me, these States General were really useful. They show that we can have deep disagreements on the vision of the mountain and economic interests, but that deep down, we are on the same boat. And the event made it possible to open the dialogue. It was a strong democratic time, from which the Future Mountain Engineering Plan emerged. It's not nothing! The territories were supported thanks to the Estates General: we had never had human engineering before, we mainly invested in developments and there, the State decided to support the tourism transition. On the other hand, let's be clear, things are not going fast enough and we are not all going in the same direction. But I think it mattered, that it created the culture of working together. It remains to be seen how we maintain it.

© Capucine Veuillet

In November 2024, you gave this book in person to Agnès Pannier-Runacher, then Minister of Energy Transition, Energy, Climate and Risk Prevention. A few days before, interviewed by our colleagues from Dauphiné Libéréshe declared: “We will have to reinvent our leisure activities in the mountains”. She hadn't read your book but she uses the same elements of language. Is this a good sign?

I think this is going in the right direction. The question is precisely how we “reinvent”. It's not just about leisure, it's about our way of life! I meet political figures, economic players, bosses, elected officials… Overall, we all know that we need to change. The problem is that we all know we have things to lose and we don't know what we can gain. This is what we need to talk about now! How do we keep our territory alive? The crises we are currently experiencing in the mountains can be a great opportunity to re-examine why we live in these areas: what do we want to do there? What do we want to make people dream about?

What I try to develop a lot in chapter 3 is the idea of continuing to welcome people in the mountains while being deeply anchored in the environment in which we are. Let me explain: I think that the mountains will always attract, whether we have snow or not in winter. It is even desirable that we take people to the mountains because we are more and more urban and we suffer from it, society is sick of our way of life and the mountains heal physically and mentally. So yes, we must mourn the ski income, the strictly financial aspect, and find meaning, create new jobs, new perspectives.