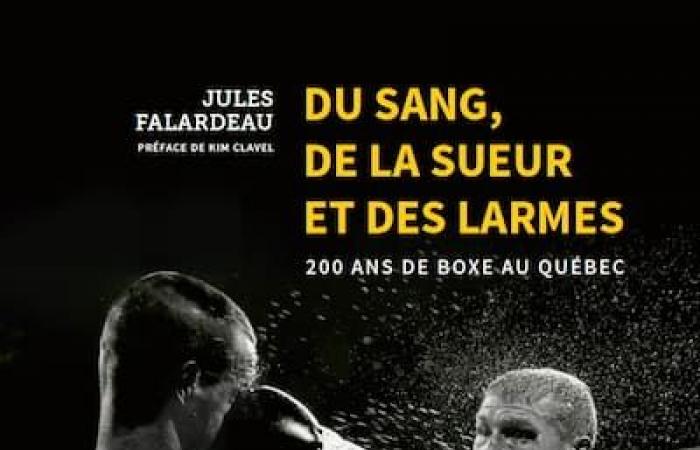

Fighting bare-handed for 20, 30 or even 50 rounds was not uncommon in the 1800s, although a law once banned fighting in Montreal. This is one of the parts of History described in the book Blood, sweat and tearsa thrilling overview of 200 years of boxing in Quebec.

• Also read: A book traces the lives of Quebecers who became heroes with fists

“I tried to imagine the lives of these guys, including George “Kid” Lavigne, who had French-Canadian origins and whom I discovered, just like Eugène Brosseau. Lavigne ends up as henchman of a small bandit who does contracts for Henry Ford. All these stories are epic,” reveals author Jules Falardeau.

Boxer Eugène Brosseau during a training camp in the Longueuil countryside in the early 1900s.

Photo provided by FONDS LAPRESSE

The latter does not claim to have written an encyclopedia, even if the word was used in the preface by Kim Clavel, a champion “whom we adopted at a time when men’s boxing was not at its best. best”.

“I went with the 40 boxers that I considered notable and those who appealed to me more. There are some who perhaps don’t have the same importance in the ring, but who brought something different. I think of Deano Clavet, who was an actor, or Reggie Chartrand, the activist,” explains the documentary filmmaker The Noble Art, Reggie Chartrand: Quebec patriot et Brothers in Arms.

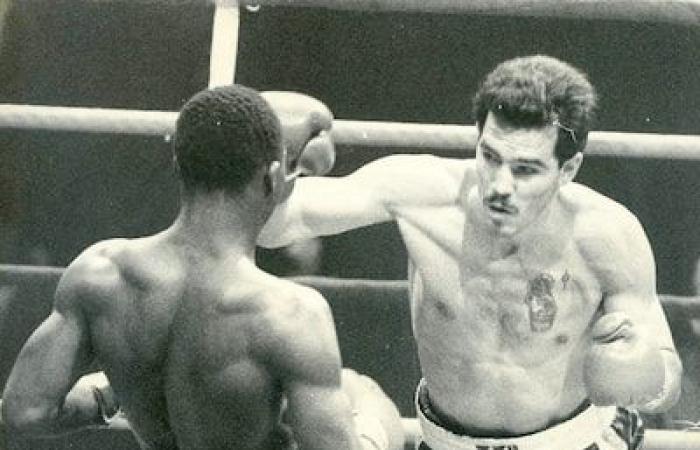

Deano Clavet (right), seen here in action in the ring against Wilson Fraser in 1983, became an actor after his boxing career.

Photo d’archives

From Jack Delaney, Quebec’s first world champion, Lou Brouillard, one of the three local athletes inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame (with Delaney and Arturo Gatti), via Yvon Durelle, from the Hilton family to Éric Lucas, Adonis Stevenson, Lucian Bute, Jean Pascal, Marie-Eve Dicaire and Artur Beterbiev, the greatest have their place in this magnificently illustrated book published in Editions of the Journal.

Marie-Eve Dicaire became world champion in 2018 after defeating Chris Namus at the Videotron Center in Quebec.

Photo DIDIER DEBUSSCHERE

Thanks to the “Poet”

It’s not new that Jules Falardeau has been a boxing fan. At 6 or 7 years old, his father Pierre took him to see an amateur gala. But it was at the age of 12, when he attended a fight by Stéphane Ouellet “Le Poète”, that his fascination with this discipline was born.

“He was spectacular during his entrance, with the music of Vangelis. Usually, boxers come in to rock tunes […]but there, Ouellet arrives with choirs, grandiose music, the lights closed… what an atmosphere! the 39-year-old recalls.

And the human aspect behind the courageous pugilists, many of whom come from modest backgrounds and use sport as a social elevator, touches him deeply.

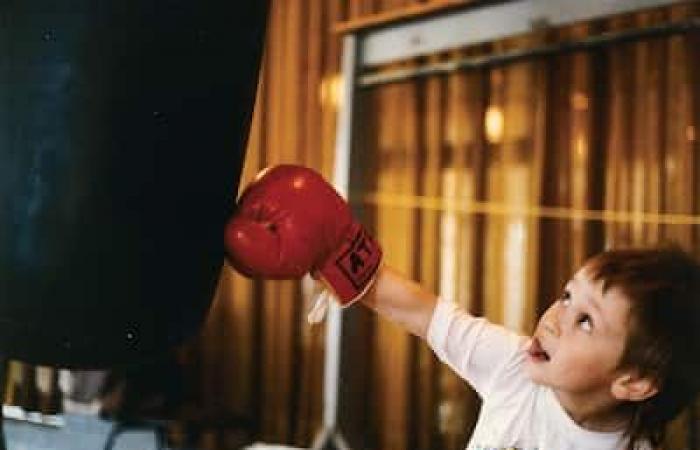

The filmmaker Jules Falardeau who, as a child around 6-7 years old, hit a bag with boxing gloves at the Paul-Sauvé Center in Montreal, during the filming of the film “Le Steak”, directed by his parents, Manon Leriche and Pierre Falardeau, and broadcast in 1992.

Photo provided by MANON LERICHE

Not hungry enough

A few years later, Jules Falardeau put on the gloves in training, without ever fighting in a ring. He wasn’t hungry enough.

“It wasn’t my only chance to break through, to move up the ladder. I saw it in a more sporting spirit. Someone who just has boxing as a hope, he will give it his all. Boxers are not ordinary people. We are not all ready to make this kind of sacrifice,” confirms the man who, as a child, visited the set of the film Le Steakdirected by his parents, Pierre and Manon, and recounting the life of Gaëtan Hart.

Author and filmmaker Jules Falardeau.

Photo Agence QMI, JOEL LEMAY

Régis Lévesque

If Jules Falardeau had made his living in the boxing world, he might have been an “honest” promoter of the 1920s or “the guy who opens the cables.” Régis Lévesque, the only character who is not an athlete to have a profile in his book, would have been his model.

“He worked in a lumberyard in Trois-Rivières and said: ‘Every day, I had my lunch box with two sandwiches and a May West calisse. This can’t be my life. One day, I’m going to throw my lunch box at my arm’s length.” He decided to mortgage his house and go into promotion, without studying marketing. He just had his instincts. He had managed to find a fiber by creating linguistic rivalries between boxers and cities. There were local fights without stakes which brought together 20,000 people,” says the author.

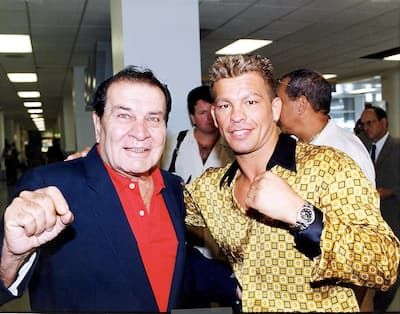

The promoter Régis Lévesque with Arturo Gatti in 2004.

Photo d’archives

A polarizing sport

A sport whose ultimate objective is to inflict a concussion by knocking your opponent to the mat can only be polarizing. But the two pugilists are consenting and aware of the risks, an aspect that Jules Falardeau did not fail to emphasize in his new work.

“I think that someone who takes the time to read the book will understand more things in the face of their prejudices. That doesn’t mean he’ll change his mind,” notes the author, who is not a big fan of ring girls and boxer commercials.

Amateurs have preconceived ideas too. Some denigrate athletes by calling them hams. You need stooges to help a boxer progress. But sometimes, like on Tinder, “the guy doesn’t look the same as on his profile!”

“Even if the other is overweight, it takes courage to step into the arena. Looking at the appearance or the musculature of a boxer, I would not go against him at all,” admits Jules Falardeau.

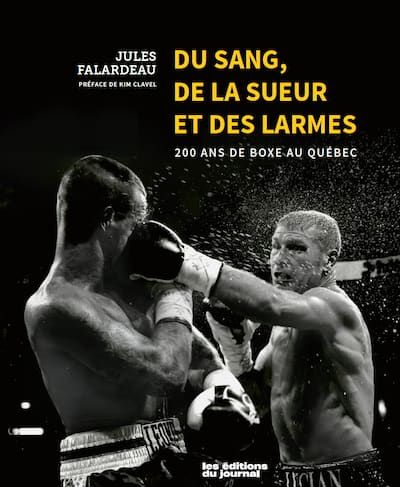

Photo provided by LES ÉDITIONS DU JOURNAL

For everyone

He believes that his work will please both fans of the noble art and initiates.

“They don’t necessarily know the stories of the boxers of the 1920s. And I want someone who isn’t into boxing or who doesn’t even have an interest to be able to find what they’re looking for. I’m doing a refresher course to explain the basics, the rules, the weight, the hierarchy in a gym, etc.”

After having gone through some 300 pages, the reader will also be able to take part in the game of comparisons with the ranking of the best local boxers from the author and some experts, in addition to the top 5 spectacular fights held on Quebec soil.

Jean Pascal hit Bernard Hopkins in the face, in 2011, at the Bell Centre.

Photo BEN PELOSSE