Morocco intensifies its preparation for disasters and emergencies by launching the construction of essential reserve platforms. Under the royal impetus, these platforms will extend through the 12 regions of the kingdom. This project, with a budget of 7 billion dirhams, aims to rescue, relieve and assist the populations affected by natural disasters.

Faced with tragic scenarios such as the earthquake of Al Haouz in September 2023, which caused thousands of deaths and left many homeless people, this initiative is part of the Moroccan tradition of crisis management.

Throughout its history, Morocco has faced various natural disasters, including floods, droughts, famines and epidemics. Each time, Moroccans have implemented strategies to overcome these crises, based on dedicated institutions, infrastructure, religious structures or acts of solidarity.

In this article, Yabiladi explores how Morocco has historically responded to the unforeseen events and its crisis management strategies.

Igoudar, storage fortresses

Moroccans have long seized the importance of food security in times of crisis, and food storage is one of their ancestral traditions. The Igoudar, plural of Agadir, are collective storage facilities traditionally built by the tribes of the regions of the anti-Atlas and the High Atlas to prepare for periods of shortage.

Considered the first banks, these fortified storage structures were strategically located in height, with thick stone or clay walls. From a distance, they look like fortresses or small castles, with towers, narrow entrances and complex locking systems. Inside, they house floors and small rooms that serve as chests for grains, jewelry and important documents, known locally under the name of Arraten.

The French ethnographer Jacques Meunier studied the Igoudar and explains that they made it possible to face “insufficient production to meet the needs and the uncertainty of the crops – for example, in the region of the Souss, where a harvest on only four is good”. “The distance from the markets and the difficulty of transport make any rapid and regular replenishment impossible,” he said, highlighting the geographic challenges of the region.

One of the wonders of the Igoudar lies in their ingenious storage system, crucial for long -term conservation, especially during bad harvests and famines. “Active ventilation prevented the grain from overheating”, with some Igoudar capable of keeping the grain for twenty-five to thirty years.

The Igoudar also played a role in solidarity in times of crisis. Posting grain in these chests required compulsory contributions, redistributed after harvests to ensure that no member of the tribe lacks food, thus illustrating solidarity and ingenuity in the face of adversity.

rich and powerful zawiyas

-What to do when the crisis persists and hunger settles, exhausting the reserves? Immigration due to disasters, diseases or hunger has been a reality in the history of Morocco, with many refuge researchers turning to other less affected regions or tribes. Some found refuge in the Zawiyas, Mausoleées Sufis who gained importance in Morocco in the 15th century and spread across the country.

These powerful institutions, often supported by donations (gifts or Hadiyas, Tributs or Zyaras, and endowments or hibas), offered protection, not only against Makhzen but also against hunger and other difficulties. The Moroccan ethnographer Mohamed Maarouf writes in a multidisciplinary Approach to Moroccan Magical Beliefs and Practices that the Zawiyas “offered protection to the disadvantaged peasants overwhelmed by the heavy taxation of the makhzen … Those who could not work were looking for the protection of the saints, offering their lands to chorfa in exchange for a shelter, food and lifetime protection ”. The Zawiyas also offered charity to the poor, residents, servants and slaves, adds Maarouf.

According to Maarouf, the Zawiyas held considerable power from the Merinid dynasty in the 13th century to the Alawite dynasty in the 17th century, especially in times of famine and epidemics.

Loans, charity and other solutions

In times of shortage, drought and famine, Moroccan sultans even lent money to tribes to revive their cultures. In his book on the history of famines and epidemics in Morocco in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Moroccan historian Mohamed Amine El Bezzaz describes how the Sultan lent money to the Beni Ahsan tribe near Rabat during the difficult agricultural season of 1780-1781. He writes: “Due to the famine that struck the farmers, a large part of the land has remained fallow. In certain areas of the Gharb region, the recovery was only possible thanks to the help of the Makhzen, because the sultan lent to the Beni Ahsan tribe an important sum to help cultivate part of their land. “

When the Sultan or the Makhzen could not provide loans, the population in distress benefited from the Waqfs. El Bezzaz notes: “Those who saved and stored provisions were, of course, the rich. As for the poor, they had nothing to save. However, they benefited from acts of charity and public benevolence. ”

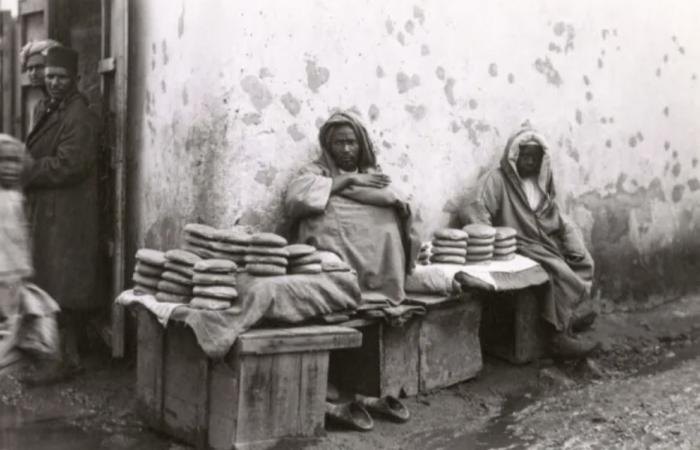

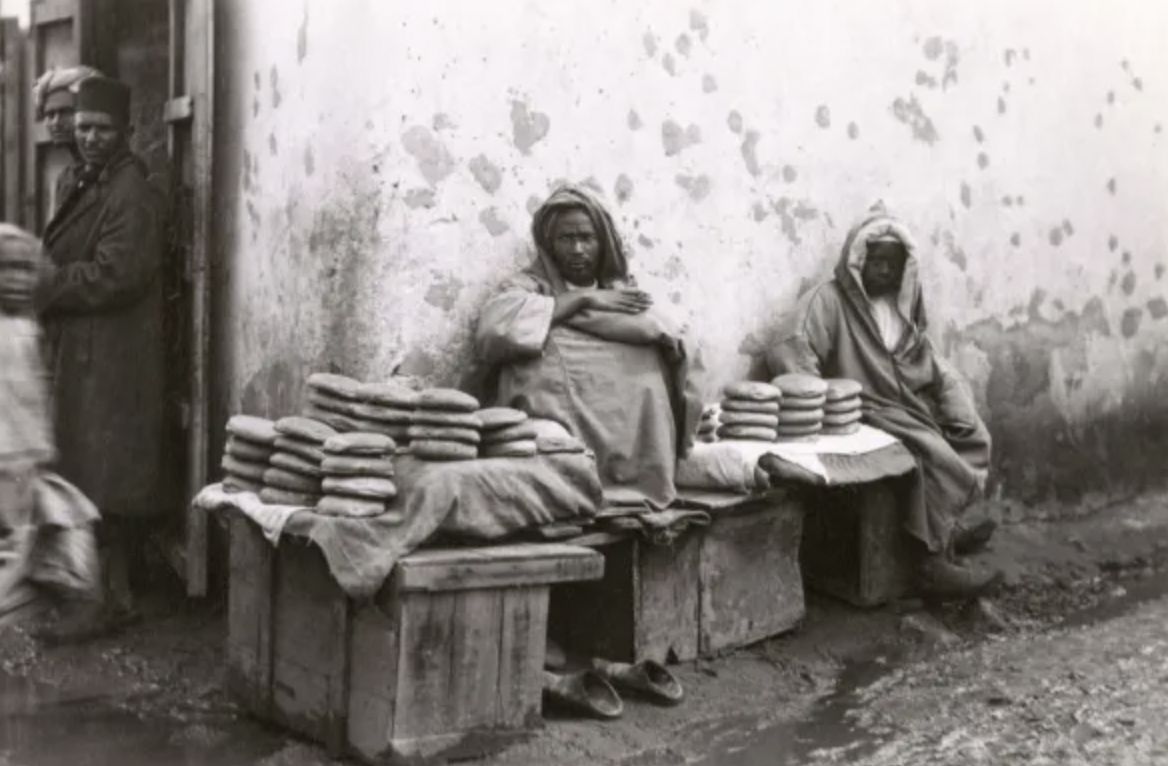

“No Moroccan city was without families who devoted part of their property to social assistance, known as AWQAF (endowments), which were specifically allocated, for example, to the weekly bread distribution – one of the most common forms of charity.”

The legal documents and the notarial archives of Tétouan dating from the 18th century bear witness to these charitable initiatives, including that where a woman from Tetouan has bequeathed a third of her heritage to finance the purchase of bread to distribute to the needy. This even earned this commodity the famous name of “Waqf du Pain”.

Other notable strategies to cope with food and water shortages and calamities included infrastructure built both by the makhzen and by the people, such as the systems of matmoura who stored the grain in pits dug in the soil, as well as tanks such as Sahrij water built by Moulay Ismail in Meknes, as well as neighboring storage complexes, formerly taken for its stables, to store grains.