Inspired by the landscapes and territories transformed by mass consumption, Wally Dion, an Indigenous man from Saskatchewan, decided to use electronic waste to create works of art.

If for a few years Wally Dion, originally from the Saulteaux First Nation of Yellow Quill in Saskatchewan, was a social worker, art never really left him. His father was also very creative

more he was more or less successful because of his alcoholism

says Wally Dion in an interview with Espaces nationaux.

He also believes he inherited from his father this desire to work with his hands, with the added desire to fight against injustice.

This is how Wally Dion began studying art at the University of Saskatchewan. In 2006, he decided to pull the trigger

and to get into art

including his first major series of portraits entitled The Red Worker.

Open in full screen mode

Wally Dion also paints works that highlight Indigenous people.

Photo: Courtesy: Wally Dion

Inspired by the style of portraits from the former USSR, this series depicts indigenous men and women at work. I wanted to break the stereotype of the “lazy Indian”

he says.

Wally Dion presents himself as interested in environmental and social issues, questions of justice, politics and history. And art is an outlet.

I can see the things that are wrong in the world and I deal with them through my art

he explains.

The desire to highlight these questions pushes him to work in parallel on a project in which he uses electrical circuits. It actually combines two ideas that are running through his head: illustrating indigenous women at work on the one hand, and technologies on the other.

Two themes which, a priori, have nothing to do with each other.

Open in full screen mode

Artist Wally Dion made a series of circuit board quilts.

Photo: Courtesy: Wally Dion

But Wally Dion manages to unite them by creating quilts, a symbol of the work of indigenous women, by assembling old printed circuits

The circuit board became the symbol of women working together in quilt making

explains the artist.

It is not without reason that Wally Dion specifically chose the quilt. It was a necessity for many communities: used clothing and blankets were cut up and transformed into new blankets. For Aboriginal people, quilts have significant cultural value.

Moreover, around 2008, Wally Dion had already designed a first series of translucent quilts called Grass Quilts.

Open in full screen mode

Wally Dion has set a goal: to achieve the excellence of Kent Monkman, a Cree artist from Manitoba.

Photo: Courtesy: Wally Dion

What lies underground

Still using printed circuits, Wally Dion also tackles the extractive industry and what it can represent from a more spiritual point of view in the series Thunderbird. We sometimes recognize in the works of this series the skeleton of a thunderbird.

It is a legendary creature that exists in the art and oral traditions of many nations in North America. This animal is also linked to electricity and storms

adds Wally Dion.

I'm talking about how these giants can be in the ground, in the earth. I was thinking particularly about the oil sands of northern Alberta and how [la machinerie] scrapes the earth to extract the oil. A rich land. And I said to myself that everything else that's in this land, they don't care one bit, whether it's human remains or something else.

further explains Mr. Dion.

Open in full screen mode

The series includes several works that highlight printed circuits whose components come from the extractive industry.

Photo: Courtesy: Wally Dion

The artist, through this series, highlights that consumers care little about how the components found in their electronic devices are produced.

The future is much more important for society. And in this sense, people are ready to completely decimate the Earth.

But he also seems to have a certain attachment to the past.

It evokes dinosaur fossils, and the earth itself which dates from a distant era. Oil is something from the past, buried for millions of years. When we burn fossil fuels, like tar sands oil, we are taking something that has been buried for millions of years and bringing it back in 2024

he says.

The artist goes even further in his reflection. When fossil fuels are extracted from the earth, skeletons are produced, including that of the thunderbird. Then by burning the gasoline, we send the thunderbird back into the atmosphere.

Considered as fossils or as a living prophecy, THE Thunderbirds are extracted from the tar sands of northern Alberta and resurrected to live among human beings

thanks to extractivism, he explains.

Making another place for indigenous works

In his work as an artist, Wally Dion has set himself a goal: to achieve excellence in Kent Monkmana Cree member of the community of Fisher Riverin Manitoba. The latter used colonial images a lot to change their meaning.

He also advocates for the inclusion of indigenous art in art in general, without locking it into a category reserved for indigenous artists. We must insert them into our history because of their work, their contribution, not just because they are indigenous

he explains.

Open in full screen mode

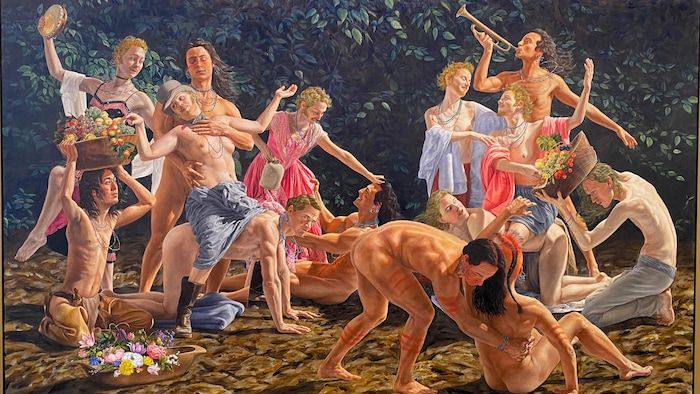

The painting « Bacchanal » by Kent Monkman.

Photo: - / Hadrien Volle

Wally Dion also believes that Indigenous art must be observed under the critical lens of artists, so that it make our art stronger

. Because when it is non-indigenous people who criticize indigenous art, there is always the risk that this will be seen as racism according to him.

This is why, he says, contemporary indigenous works have not been well reviewed

.

We must therefore seize the opportunity to bring indigenous art out of its environment, to make it more accessible to Canada as a whole, continues the artist, knowing that this opinion sometimes makes one cringe

.

Open in full screen mode

The artist now lives in the United States but returns to Canada, notably for exhibitions.

Photo: Courtesy: Wally Dion

Currently, Wally Dion is working on making a quilt, this time in fabric, to talk about the Saskatchewan prairies.

I want her to say “Land Back”because this sentence means a lot of things. I'm going to bring her back [la courtepointe] in the meadows, hang it using tepee poles, see what it looks like when surrounded by grass

he explains.

The idea for him is to work outside his studio in New York State, to return to the land, in the open air

and also to move my artistic practice away from museums and galleries and into the public itself

.