It is an exhibition that is both scholarly and burning that the Louvre Museum is offering this fall around the figures of the madman. A few days before its inauguration, the film “Joker.” Folie à deux” – chance does things well. These images of crazy people and madness resonate surprisingly with current events in the world and its upheavals. In a related, although different, register, the Mucem in Marseille will present this winter “On the track!” Clowns, clowns and acrobats”: the figure of the clown is a distant heritage of that of the madman. “There is something of the spirit of the times in this subject, of the desire to return to laughter and disorder,” explains Élisabeth Antoine-König, co-curator of the Louvre exhibition with Pierre-Yves Le Pogam. .

“Infinite is the number of madmen”, we can read from the first steps of this journey which presents different facets of madness. The phrase, taken from Ecclesiastes, appears on an engraving decorated with proverbs, in which a knight presents for all face, under his helmet, the lines of a planisphere (“O head worthy of the hellebore”) – strange vision a diver from “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea” or a surrealist character from a painting by René Magritte.

« Portrait d'un fou », Marx Reichlich, Tyrol, verse 1519-1520.

© DR

Throughout the rooms, there are numerous scenes of courtly love, such as the engraving of “Couple of lovers at the fountain” (around 1490) by Alart du Hameel, or the very busy couples in the lush garden represented on the tapestry “The Snack” (around 1520). The madmen also remind us that we are going to die, for example in the “Copy of the Basel Dance of Death” by Johann Rudolf Feyerabend (1806), the 60 meter long original of which dates back to 1439. They appear in fights, like the tournament scene from one side of the goldsmith's bench of Prince Elector Augustus I of Saxony (1565) – this monumental and luxuriously utilitarian object decorated with marquetry was used to pull metal wires. They are also dancers and musicians, represented as such allegorically or in the form of portraits such as that of Claus Narren von Ranstedt (around 1550).

“Madness is a falsely marginal subject”

The medieval era and the Renaissance occupy most of the visit. Literally and figuratively, the madman seems to move from the margins of illuminated books, where we see dragons with the heads of men (summer breviary of Renaud de Bar, bishop of Metz, 1302-1305), to the center of society. “Madness is a falsely marginal subject. In tapestries, paintings, sculptures and architecture, the insane quickly appear as prominent figures. We talk about “figures of the madman” because they are symbolic madmen who represent the world upside down,” adds Élisabeth Antoine-König. The origin of this vision is anchored in the Catholic religion, through the image of the fool rejecting God. But it is also deployed in secular objects, such as the curious aquamanile (a container for washing hands before mass or at banquets) which depicts with great humor the beautiful Phyllis riding poor Aristotle in love with her ( around 1380). The madman warns against human folly.

“Stanczyk during a ball at the court of Queen Bona after the loss of Smolensk”, Jan Matejko, Krakow, 1862.

© All rights reserved.

Some objects are surprising in their ambivalence: like the very strange napkin holder representing a madman embracing a woman by Arnt van Tricht (active between 1530 and 1570), we do not know whether it carries a moralizing or saucy message. Others delight with the humor and oddity that they convey: the “crazy-faced Armet of Henry VIII, King of England” by Konrad Seusenhofer (1511-1514), head of armor with horns of goat and glasses, is a curious diplomatic gift offered by an emperor to a king. In the first quarter of the 16th century, at the time of the publication of Erasmus's “In Praise of Madness”, which Hans Holbein painted in the guise of a wise man, the figure of the madman reached its peak in all the spheres of society.

The rest after this ad

The masterpieces follow one another, such as “The Swindler”, or even “The Ship of Fools” by Hieronymus Bosch, a delirious boat in which a character stands out, dressed as a madman and with a hammer in his hand as a scepter. , he drinks from a cup and stays away from the other drunken passengers. At a time when Europe is experiencing significant cultural and social transformations, this figure serves to convey ideas of subversion.

The rest of the exhibition is devoted to the muting of these representations in the 17th century, due to the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation, then the philosophy of the Enlightenment, which was not favorable to festivals, carnivals or to overflows. It was not until the end of the 18th century that they reappeared. In 1799, Goya engraved the image of a sleeping artist surrounded by chimeras: “The sleep of reason breeds monsters”. An atmosphere reminiscent of the gargoyles with disturbing shadows desired by Viollet-le-Duc for Notre-Dame de Paris. The subject of mental illness, previously non-existent, is brought to light. In his large painting, Tony Robert-Fleury shows Doctor Pinel, chief physician at Salpêtrière, whose deputy is freeing the insane from their shackles in 1795, an image of the first research in psychiatry (1876). While in the past we only talked about her “absences”, Queen Joanna the Mad is represented in crazy postures. Johann Heinrich Füssli shows “Lady MacBeth walking in her sleep” (around 1784), looking hallucinated, in a monumental canvas, while Théodore Géricault paints a little later “The crazy monomaniac of the game” (1819-1822). The exhibition ends with a version of Gustave Courbet's famous self-portrait, “Man Driven Mad by Fear” (1844). The painter wears the striped costume of a jester, his hand extended towards an invisible abyss, opening the door to the vision conveyed by the 20th century, of the madman as the figure of the artist.

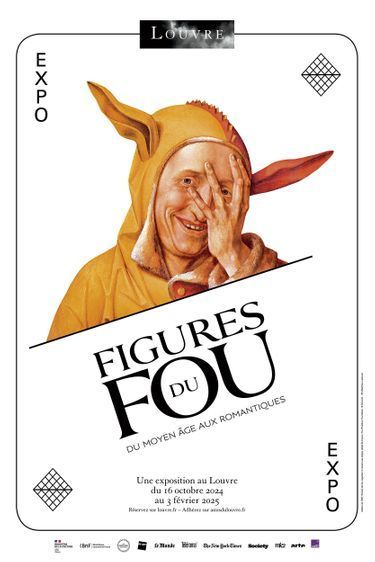

“Figures of the madman. From the Middle Ages to the Romantics”, until February 3, 2025 at the Louvre Museum, in Paris (I).

© DR