It is a very dense, but fascinating exhibition that the Louvre Museum is offering. Entitled “Figures of the Madman”, it explores, in 340 works, paintings, sculptures, illuminated manuscripts, texts, costumes and various objects, the way in which our view of madness has changed, from the Middle Ages to the 19th century.e century.

The first part, the most surprising, describes the subject up to the Renaissance (of the second part, that on modern and romantic madness, we could have done another exhibition): at the time, madmen were everywhere. Not as defined by contemporary psychiatry, these then belong at best to exorcism, at worst to the stake, nor the simple-minded (the kingdom of God belongs to them), but those who manifest what we could call for an ordinary madness: that of all men – and women – who, permanently or occasionally (during carnival times for example), indulge their passions. We have here a eulogy of madness as conceived by the art of Northern Europe (Flemish, Germanic, Anglo-Saxon and French worlds), where a fascinating period is revealed which will culminate with some determining texts, such as The Ship of Foolspublished by Sébastien Brant in 1494, followed, in the form of an ironic response, by The Praise of Madnessby Erasmus (1511).

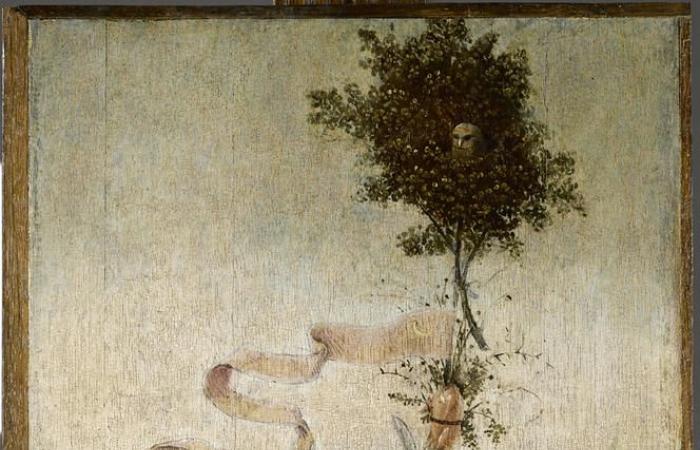

The first opposes the crises of his time (the decadence of the morals of the clerics, the excesses that money allows, the various heresies which undermine the order of the world) with moderation and wisdom, under the aegis of the emperor and of the Roman Catholic Church. He is one of those who think that dangerous undertakings displease God. Which soon after allowed the Franciscan Thomas Murner to present Luther and his disciples as madmen who should be eradicated. Erasmus, for his part, comes to wonder if it is not the wise, the reasoners, who are the true madmen… Hieronymus Bosch gives a close vision: in his painting The Ship of Fools (around 1500), unreason reigns everywhere on the ship, except to the right of the painting where the madman, wearing his cap with bells and holding his cap, turns his back to them and quietly drinks his cup of wine, seated at the gap in a tree…

Head full of wind

Since it begins by showing marginaliathe little monsters or the grotesque characters drawn in the margins of the books, we can confess the only disappointment provided by this exhibition: the absence of the copy of The Praise of Madnessby Erasmus preserved at the Kunstmuseum in Basel, illustrated by the Holbein brothers, Ambrose and Hans the Younger. Even if a page is reproduced in the catalogue, which as a whole is an exemplary work, it is difficult to understand why an object which responded so well to the theme does not appear there. However, this aspect is only a small part of the exhibition, which is organized thematically. We certainly begin with the relationship between the madman and God, but we also discover love madness, the king’s madmen, the madmen in the city, then, with the advent of modern times, the first attempts to treat the insane, up to the beginnings of psychiatry.

You have 60.07% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.