The challenge for the new coalition in power in Damascus is to reunify the multi-faith and multi-ethnic Syrian population.

What future for the Syrian people? Bashar al-Assad leaves behind a country bloodless and ravaged by thirteen years of civil war. To establish his authority, the Syrian dictator favored his own community, the Alawites, but he also counted on other communities by banking on the fragmentation of his people. Because Syria, which has a population of nearly 20 million inhabitants, is a mosaic of religions and ethnic groups. What are these different communities? After the fall of the regime, how will they live together? Should we trust the new power in place, the HTS group, which claims to respect the country's minorities?

To answer these questions, franceinfo speaks with Laura Ruiz de Elvira, research fellow at IRD, the Research Institute for Development, specialist in Syria to whom she, in particular, devoted her thesis.

franceinfo: How is the Syrian population made up?

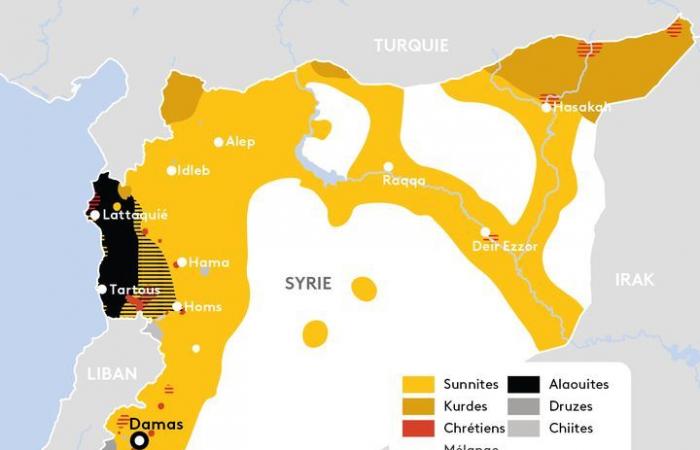

Laura Ruiz de Elvira: The country is made up of different communities, religious and ethnic. 90% of the population is Muslim, and within this Muslim population, there are between 70 and 75% Sunnis, one of the two main currents of Islam. But they are not the only ones, there are between 7 and 10% Alawites. It is a dissident branch from Shiism, the other major current of Islam, and it is the minority from which the Assads come. Then, Christians represent around 10% of the Syrian population and they themselves are divided into multiple small communities: there are the Greek Orthodox, the Greek Catholics, the Syriac Orthodox, or even the Armenians, who are both a religious and ethnic minority.

There are also 3% Druze, who are mainly in southern Syria. It is a branch of Islam which is also an ultra-minority, which has its own history and its own symbols and which straddles Syria, Lebanon and Palestine. Finally, there are the Kurds who are Sunnis and who represent around 10% of the Syrian population. Apart from Kurds and Armenians, Arabs are the majority ethnic group in Syria.

What was the relationship of the different communities with the regime of Bashar al-Assad?

We have always talked about Alawite power, but it needs to be qualified a little. Obviously, the strongest bases were Alawites, but this community was taken hostage, already before 2011 and then from 2011, with a lot of young Alawites sent to war without being able to say no. Thus, the support of the Alawite community for the regime of Bashar al-Assad during the last ten years has deteriorated, also due to increasingly poor economic conditions. Moreover, there was no real resistance to the advance of HTS and the community did not fight for the regime. We even saw demonstrations in Tartous and Latakia, which are strongholds of the Alawite community, with the flags of the Revolution.

“Communitarianism is a concept to be handled with delicacy, it has been used as a tool of governance for decades by the Assad regime.”

Laura Ruiz de Elvira, Syria specialistat franceinfo

To govern, the regime has always co-opted elements of the different communities by giving their elites economic privileges and limited political power, that is to say guarantees so that they do not challenge the power in place. The regime thus counted on the support of Christian religious figures. During my investigations in Syria in the 2000s, Christians themselves told me that they benefited from a margin of maneuver in the management of social and associative affairs, from which Sunnis did not benefit. The regime also relied on the Sunni majority, in particular its elites, who benefited from the economic liberalization of the 2000s. But the Sunnis were also greatly oppressed, particularly after 2011. I realized that there was, among some Sunnis, a feeling of marginalization, of contempt on the part of those in power, of not being able to express their faith, and to practice their activities quietly.

As for the Kurds, they were the community most repressed by the regime, particularly before the revolution. Before 2011, thousands of Kurds did not have nationality. And in 2011, the regime granted them nationality to ensure that they did not mobilize.

Is Syria a mosaic or a nation?

We cannot therefore deny the existence of communitarianism, which has been strengthened during the last ten years of war. But many Syrians are not comfortable with this community reading which would erase the vision of their country as a nation, precisely. We must talk about Syria as a nation, which has a very long history and which has pride. A sense of national pride was restored at the time of the revolution, after decades of Baathism (the party of al-Assad), which had rewritten the country's history to its liking. This national pride is found today with the fall of the regime. Let us remember that in 2011, one of the most sung slogans was “The Syrian people are one!” and this slogan was also taken up during the fall of the regime.

What does HTS’s coming to power mean for Syrians?

There is relief, there is joy, there is even amazement. That the regime really fell after all these years seemed impossible, very few people still believed it. But at the same time, Syrians remain vigilant, wary and waiting to see what will happen. Because many revolutionaries had been persecuted, first by Daesh then by HTS in Idlib. So obviously, for them, for the Syrians who are more secular and for the minorities, this is not the power they wanted to see arrive in Damascus. The Syrians are not naive, they know that they face immense challenges, that it will be very complicated. And besides, there are already beginning to be signs of impatience and an expression of this distrust. There were rallies in Aleppo calling on HTS to open the prisons in Idlib. And in Damascus, on December 19, demonstrators demanded a “United, civil and secular state”.

Among my contacts, I see many who today express their dissatisfaction with the figures who have been appointed to this interim interim government, because they are figures close to al-Joulani. They tell me: “We did not get rid of Al-Assad to have today the al-Charaa family” (al-Joulani's birth name).

Today, is there a desire for union?

Absolutely, there really is this desire to overcome the fragmentation of the people and to build a new country on new foundations. But it is obvious that not all communities project themselves in the same way. Today, the Kurdish population and the Alawite population are more afraid than the other components of the country. Even if, regarding the Alawites, there have been no reprisals or resistance since the fall of the Bashar al-Assad regime.

Concerning the Kurds, there is a lot of tension in the north-east of Syria where they are forced to retreat more and more since they have already lost territory. The various rebel groups, which form the Syrian National Army (SNA) and which are in fact led by Turkey, aret launched an offensive against the territories controlled by the autonomous administration of the Kurds. So today, a lot of questions are being asked about what will happen for this community.

The future of the Kurds will also depend on what the Kurds themselves decide to do: will they join the national march or will they ask to maintain their autonomy? We can clearly see that today, within the autonomous administration itself, there are some who are willing to negotiate and dialogue with the new power to see how they can maintain a certain autonomy And, there are some who are rather in a hard line to pursue their project of autonomy and which tend rather towards confrontation.

Can we believe the promises given by HTS?

It's difficult to plan ahead, but what we can do is observe what has been done so far, in Idlib where HTS was in power. Scholars have highlighted the fact that al-Joulani made concessions to certain minorities who were in Idlib, for example, Christians could continue to practice their worship, have their church, etc. HTS managed to govern in Idlib because they had gun power, but countrywide they are not in the same situation. There are other factions, there are many more populations to manage, so they won't be able to do exactly the same thing they did in Idlib, without being challenged.

“Today, we see that HTS is giving guarantees to everyone to reassure the different communities and that there have been no abuses or reprisals, for example against the Alawites.”

Laura Ruiz de Elvira, Syria specialistat franceinfo

HTS really has a concern for acceptability. If they want their governance to hold, they need money for reconstruction and therefore they need international aid for the country to recover. For this international aid to arrive, they must be pragmatic and provide guarantees of inclusiveness. And HTS must be removed from the list of terrorist groups. So it's a set of elements that make it in al-Joulani's interest to continue in this line of openness and respect for different minorities.

What could be the opposition or counter-power to HTS?

The Kurdish autonomous administration already represents a form of opposition. There is also the secular opposition. Former members of the regime could also organize themselves, even if for the moment, this is not the case. HTS could also find itself facing other rebel factions who might feel that they have not gotten their share of the pie. At the level of civil society, many Syrian associations, which were established in Türkiye, are already back on the ground. They organize themselves to distribute aid, to engage in reconstruction. etc. And they may possibly constitute opposition to HTS. So HTS will have to be sufficiently inclusive and pragmatic if they want to retain power, otherwise they will find themselves facing a lot of challenges. And there are already signs that we are not going to let them do what they want.

Can Syria also count on its diaspora?

With the exile of millions of Syrians over the last ten years, there is today a whole new generation of Syrians who are today ultra-trained, in terms of civil society, in humanitarian work, in the media, in cultural level, at the level of governance, at the level of transitional justice. Syrians who will be able to participate in the reconstruction of the country but who also have enormous expectations. They should not be put aside because otherwise they too could be part of future oppositions.

What do you think is desirable for the destiny of the Syrian people?

We will need transitional justice that moves in the direction of reparations and the determination of responsibilities. And free elections will also be needed for Syria to move forward. Former revolutionaries are already demanding the possibility of creating political parties. For the moment, we are still in the phase of euphoria, with questions, questions. But in two or three months, we will be building the new Syria and for that, we will absolutely need free elections where the parties can compete so that all Syrians can express themselves in their diversity. Without this, al-Joulani's new governance project will not be viable.