Ct is a body curled up on a stretcher in a bare room at Ibn al-Nafees hospital in Damascus. Just the day before, he couldn't remember his own name. Khaled Badawi is one of 300 inmates released from the sinister Saydnaya prison. Today, he is able to murmur a few words, we understand that he is from Aleppo, little more. “He suffers from numerous fractures, an eye injury and he is malnourished,” lists the Dr Hamam, which takes care of it.

In his small room, families take turns constantly, lingering on his swollen face, in the hope of finding the son, the brother, the father, disappeared in the macabre workings of the Syrian prison system. “Did you see my son there? He was imprisoned in 2019,” asks an elderly woman, showing him a portrait on her phone. Khaled doesn't have the strength to respond. “Since we knew his name, we were able to contact the family,” rejoices the doctor. I've been calling them non-stop since this morning, I imagine they are already on their way from Aleppo. »

Doctor Hamam tries to contact the families of Sayndaya prisoners

Hugo Lautissier

130,000 missing

Since the arrival of the Islamist rebel group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in Damascus on December 8, and the flight of Bashar al-Assad, this prison has been at the heart of attention. Everyone saw the images of HTS troops, forcing cell doors with rifle butts and those of starving prisoners, finally free, running as far as possible from their jail.

In its report published in 2017, Amnesty International describes the prison as a “human slaughterhouse” where torture, inhumane detention conditions and harsh interrogations are practiced, a symbol of the abuses of the Assad clan regime. In a 2022 report, the Saydnaya Association of Detainees and Disappeared estimated that 30,000 prisoners were tortured to death or executed between 2011 and 2018, at the height of the repression against the revolutionary movement. The bodies were never returned to their loved ones. More than 130,000 people are still missing.

Hope rekindled

For the tens of thousands of families whose loved ones have passed through Saydnaya since it opened in 1987, during the era of Hafez al-Assad, the capture of the prison has rekindled immense hope. It is visible in the Moujtahed hospital where the bodies of around forty prisoners, found in a military hospital in the capital, are exposed so that families can identify them. Hundreds of people come and go in the morgue or crowd against the entrance to the hospital, where photos of the deceased (died within the last twenty days) have been displayed.

Hugo Lautissier

In the morgue of Moujtahed hospital, families try to identify the bodies of their loved ones, detained in Saydnaya prison.

“Whoever enters Saydnaya does not leave alive but we will wait here until we know the truth”

“As doctors, we are used to seeing death, victims of war, but what we saw with these bodies was unlike anything else,” relates Muhammed Najem, surgeon at this hospital. “They all have marks of beatings on their faces and limbs. We saw broken teeth, torn nails and eyes, burns made with heated tools. »

“A camera was watching us”

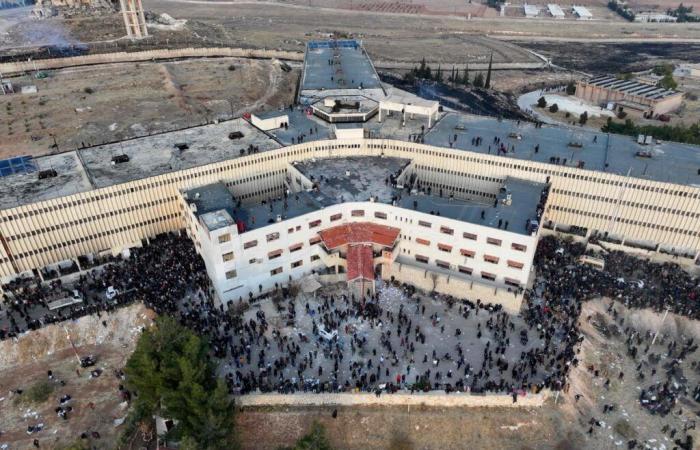

In front of Saydnaya prison, about thirty kilometers from Damascus, thousands of Syrians are flocking from the four corners of the country, looking for their loved ones. They wander in the dark corridors, in the cells where prisoners' clothes still litter the floor, looking for a clue, a trace of life. In one of them, a former prisoner, Ahmad al-Muhammed, 32, released a few years ago, is looking for his brother Anas, also detained. “The hardest part is the torture and the lack of food. We couldn't think of anything other than eating. We couldn't even think about leaving the prison, he said. We got up at 5 a.m. otherwise we were tortured. When they opened the doors, we had to cover our eyes with our hands or we were punished. We weren't even allowed to speak. In each cell there was a camera monitoring us. »

Hugo Lautissier

Ahmad al-Muhammed, 32, was imprisoned in Saydnaya and is still searching for his brother, also detained.

Abd el-Karim Aboud is from Deir ez-Zor, a city located on the banks of the Euphrates River, on the border with Iraq. When the regime's fall was announced, he took his car and drove the 450 kilometers that separate him from Saydnaya. His brother, a member of the Free Syrian Army (ASL), between 2011 and 2012, at the start of the Syrian revolution, was taken prisoner in 2019, in Damascus. “He who enters Saydnaya does not leave alive. But we will wait here until we know the truth. We just want to know,” says Abd el-Karim: “This prison is the greatest proof of Bashar al Assad’s murders, the whole world needs to see it. »