(Washington) Portland, Oregon, or Portland, Maine, Phoenix, Milwaukee or Charlotteville, the scenery changes, but it’s the same commercial suburb everywhere. The same four lane streets, plus the middle one to turn left to the same Walmart, Target, Burger King, Waffle House, Taco Bell, Starbucks or Chick-fil-A.

Posted at 5:00 a.m.

“We know America, we’re home,” Dean Moriarty tells Sal, in On the Roadduring one of their crazy crossings of the country. “I can go anywhere in America and have what I want, it’s the same in every corner, I know the people, I know what they do. »

I’ve had this feeling before. The more I wander around, however, the less I am able to speak in general about these people called “the Americans.” Every week, little cluster bombs shatter what I thought I knew. I constantly pick up the pieces to try to mentally piece together an overall picture that holds together…

The train leaves Union Station, Washington, at 4:05 p.m., arriving 20 hours later in Milwaukee.

Three months later, it seems like a stupid idea for a trip, and it was. Especially if you don’t have a bunk and you’re going to cover a political convention in the Midwest.

I sometimes have irrational enthusiasms which lead me into more or less standard paths to “meet people”.

In the United States, aside from the busy Boston-Washington corridor, this means of transportation is considered completely unglamorous, inefficient and tacky. That’s what attracted me: the slowness, the ordinary customers, the controllers with the cap and the paper ticket that they attach to your seat, the tossing, the whistling that wakes you up in the unlikely event that you were sleeping, the station names: Harpers Ferry, West Virginia; Connellsville, Pennsylvania; Elyria, Ohio; South Bend, Indiana…

It was already dark and I was looking for a place to sleep when about twenty Amish people came on board, somewhere in Pennsylvania. In the morning, when the Ohio fields turned on their lights, I found myself at the cafe next to one of them, a young father of five children. He had gone to visit a cousin in Pennsylvania and was returning to his community in Minnesota. There is a mental health center there for the Amish. He doesn’t vote. Doesn’t have electricity. Wears handmade clothes, like in the 18th centurye century. Since he works at the cart repair shop, he sees a lot of “outside” customers and has an idea of the presidential candidates. He heard Trump was better. Two of his brothers (out of eleven children) are no longer in the community, but they still see each other.

What struck me most was not the description of the “timeless” way of life, but the softness and rhythm of his voice. He told me in slow motion about the life of the fields and the crafts, detached from the hustle and bustle of political life and modernity.

PHOTO MICHAEL F MCELROY, ARCHIVES THE NEW YORK TIMES

There are approximately 400,000 Amish people in the United States.

With their round hats or their scarves in their horse cart on the shoulder of the national roads, the 400,000 Amish are the exotic survival of the first waves of European immigration to Pennsylvania. Like other groups arriving in the 17th centurye and 18e centuries in Pennsylvania, they fled war and religious persecution in Europe and came to found an ideal society here. Pacifists, anti-slavery, they largely stayed away from armed conflicts.

But they are also the version visible to the naked eye of one of the fundamental currents of this country: the desire to live free from the government. To be left alone.

In April, at the start of my stay here, I went to Montana to meet the son of the founder of a far-right militia. Dakota Adams is running for the local Democratic Party. He told me about the paranoid life his father put his family through, preparing for a possible attack by the federal government and some sort of end of the world in an explosion of violence.

PHOTO YVES BOISVERT, LA PRESSE ARCHIVES

Dakota Adams

His father, Stewart Rhodes, is serving an 18-year prison sentence for taking part in the assault on the Capitol with his “Oath Keepers”.

These far-right armed militias are marginal, but it is not only to take advantage of isolated terrain in the mountains that several have taken root in Montana, Idaho and Washington State. This immense portion of the “distant” West, developed around the railroad and mining operations, has for a century conceived a visceral distrust of the federal government.

In this same very Republican state, the “whitest” of the 50 in the Union (0.5% black), the very popular mayor of the capital is an African refugee who arrived from Liberia 32 years ago.

PHOTO JULIA NIKHINSON, ARCHIVES REUTERS

The steel structure of the Francis Scott Key Bridge rests on the container ship Daliin Baltimore Harbor.

On the other side of the country, a bridge collapsed in Baltimore, killing six Latino workers.

PHOTO MARK SCHIEFELBEIN, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

A Honduran construction worker speaks at a CASA-organized vigil for victims of the bridge collapse in Baltimore.

This major port transits mega-container ships loaded with automobiles from Mexico or Alabama, wood from Brazil, China or Canada, aluminum from Quebec, cereals, sugar, in short, everything that globalization is carrying around the world.

PHOTO STEPHANIE SCARBROUGH, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

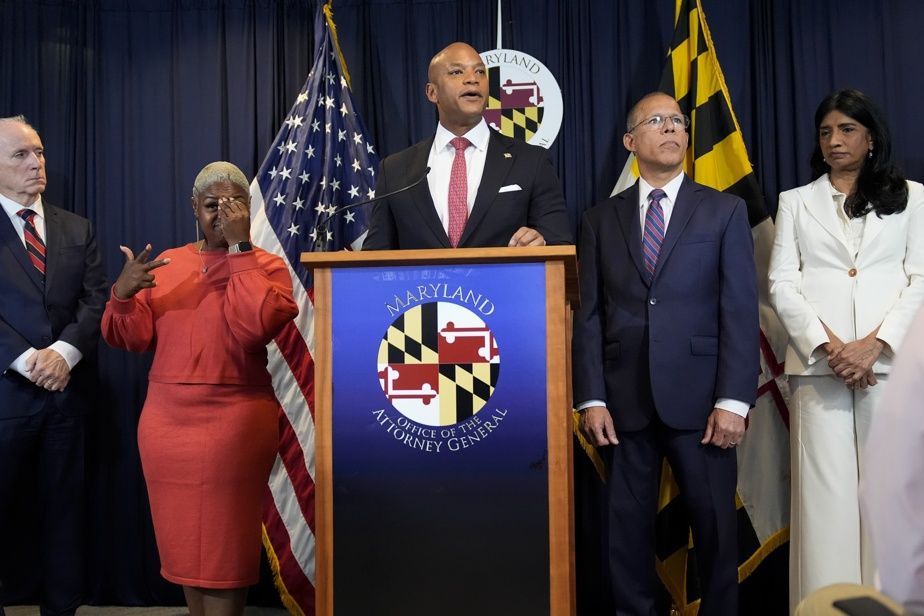

Maryland Governor Wes Moore at a press conference on September 24

I attended one of the weekly press conferences of Maryland Governor Wes Moore, a former soldier and Rhodes scholar who has not said his last political word, and it is not for nothing that he was one of the speakers at the Democratic convention. He projected a commanding image until the port fully reopened on June 12.

It also allowed part of the country to achieve this:

More than a quarter of the U.S. construction workforce is made up of recent immigrants from Mexico or South America. Some entered the country without asking permission. They are not poisoning the blood of the nation, as Donald Trump says; they repair the country and make its economic heart beat.

Still: undocumented immigrants from El Salvador or Honduras that I meet in Little Havana, in Miami, tell me that Trump is their man. Trump equals wealth, equals success. The mass expulsions promised by the Republican candidate are not for them, they are for the criminals, and good riddance…

This country that we think we know so well refuses to be summarized in sociological categories.