“The great philosophical systems,” writes the philosopher Luc Ferry, “ […] are like magnificent palaces, like castles that you must take the time to visit before criticizing them. » Stoicism, born in ancient Greece in the 4e century BCE and made famous by three great Roman thinkers — Seneca, Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius — in the first two centuries CE, is one of these castles.

This thought, in fact, as Ferry notes in Wisdoms of yesterday and today (Flammarion, 2014), “will span the entire history of philosophy” and will influence, in particular and in part, Montaigne, Spinoza, Nietzsche and Christianity. Today, we find its influence in psychology in cognitive-behavioral therapies and in a host of best-selling books on the quest for serenity.

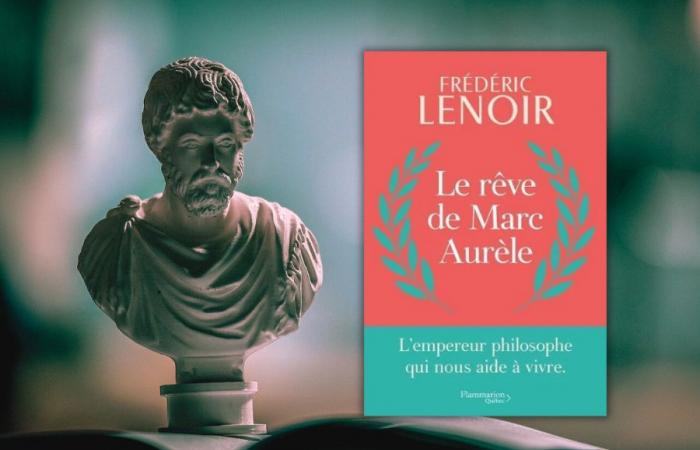

It is this magnificent palace that the philosopher and sociologist Frédéric Lenoir invites us to visit in The dream of Marcus Aurelius (Flammarion Quebec, 2024, 288 pages).

There is no doubt that Lenoir is an outstanding philosophical and theological popularizer. His works The Philosopher Christ (Lead, 2007), Socrates, Jesus, Buddha (Fayard, 2009) and The Odyssey of the Sacred (Albin Michel, 2023) are exemplary in this respect and can be read with benefit by all those interested in these major questions. His most recent essay on Stoicism is in this vein, both substantial and accessible.

An original emperor

Marcus Aurelius (121-180) is a funny philosopher. Adopted son of the Roman emperor Antoninus and emperor himself from 161 to 180, he nevertheless went down in history above all as a Stoic sage. This is rather rare in the world of crowned heads.

Even if he came into the world in an ultra-privileged environment, “within a rich, cultured family close to the highest spheres of power”, notes Lenoir, the young man, sensitive and in fragile health, prefers philosophy to power. and will only become emperor in spite of himself.

This journey perhaps explains why history will retain a good opinion of him, presenting him as a devoted and just sovereign. From a young age, in fact, Marcus Aurelius retained four things from the teaching of his masters, summarizes Lenoir: “Avoid futile activities, develop a critical mind, learn to think well through the art of philosophical dialogue and lead a austere life. »

An emperor, that said, remains an emperor, and Lenoir does not hide the dark sides of the character. During his 19-year reign, Christians and Jews, who refused to worship the Roman gods, were persecuted, slavery and the submission of women continued and colonial wars, carried out in the name of the civilizing mission of empire, will multiply. Wisdom, we see, has difficulty transcending its time and social roles.

Principles of Stoicism

The life of Marcus Aurelius, in its greatness as in its miseries, is not without link, either, with his adherence to stoicism. This philosophy is based on a few main principles that make up a vision of the world.

She first conceives the universe, that is to say all of reality, as “a large living being where everything is interdependent”, where “everything that happens is necessary”, summarizes Lenoir. Nature, which includes humans, is governed by an ordering providence that determines everything. Wisdom, therefore, consists, by reasoning, of finding our rightful place in this whole and of being satisfied with it.

For the Stoics, life is “a play in which we are the actors,” writes Lenoir. However, the role that falls to us is predetermined, already written. For one, it will be slave, for the other, emperor, without being able to change anything. The wise man’s task is to understand what role falls to him and to play it as best he can without complaining, or even finding happiness in it.

We understand the necessity, in this logic, of a second principle which postulates that “it is not reality that makes us happy or unhappy, but the opinion or representation that we have of it”, explains Lenoir. In other words, reality being what it is, that is to say necessary and determined, our happiness depends on our ability to accept it, even to love it.

From here comes the great Stoic lesson according to which it is important to distinguish what depends on us (our thoughts, our desires) from what does not (external reality, the judgments of others) in order to live well.

-Our freedom, in other words, consists of learning to accept what happens to us and to love it instead of fighting against destiny. To illustrate this lesson, Epictetus gives the example of “a dog attached by the neck to a cart pulled by two oxen which represents the power of destiny,” explains Lenoir. If the dog, frustrated by the situation, resists and refuses to follow, he will arrive at his destination injured, or even dead, after a hellish journey. Wisdom must therefore encourage him to follow the chariot obediently and voluntarily in order to take a beautiful walk with his soul at peace.

Wisdom of acceptance

Marcus Aurelius does not invent these thoughts. He found them mainly, through his masters, in his great predecessors who were Seneca (-4 to 65) and Epictetus (50 to 125 or 130). If we nevertheless consider him as a philosopher, writes Lenoir, it is therefore not because he created a new doctrine or because he advanced Stoic thought, but because he embodied it. We know this thanks to historians and thanks to the only book we know about it, Thoughts for myselftitle given to the handwritten notebook found by his soldiers in his tent the evening of his death.

Stoicism, it is obvious, has its greatness. He tells us, notes Lenoir, that “we can be happy with few things”, that our judgments about things sometimes cause more of our unhappiness than the things themselves, that there is no point in lamenting about the past or to hope that happiness is found in the future and that, as everything is interdependent in the world, “the concern for individual happiness must always be linked to the concern for the common good”.

This Stoicism, Lenoir specifies, is also not unrelated to Christianity through its reference to good providence, through its principle according to which all human beings are of the same nature, through its insistence on the duty of benevolence towards others and by his acceptance of death as a necessary experience.

When we worry too much about peccadilloes, when we blacken our current situation by thinking that somewhere else or later it would be better, when fate places solid obstacles in our path, a dose of stoicism does not help. wrong.

The death of a loved one, for example, is a difficult ordeal. Tears, then, are not forbidden. Revolt against this reality, the Stoics say, however, does not bring about anything good; acceptance is better. They are not wrong. I can’t change anything about my mother’s death which saddens me. However, I can consider it an inevitable event in life and give thanks for the luck I had to have such a mother. Easy to say, hard to do, but no one said wisdom was a sinecure. I am, in this sense, a bit of a stoic.

Humanism of revolt

Stoicism, however, has its limits. His providentialist and determinist metaphysics, which postulates that everything is decided in advance, annihilates freedom, in its modern sense, to recognize only the possibility of interior freedom. She says, in effect, that I cannot change the world, but only my judgment on the world.

This appears to me not only contradictory – if everything is determined, how can I have the freedom to modify my thoughts, which are themselves determined, logically – but, even more, humanly unacceptable. Evil — injustice, wickedness, violence, etc. — exists, and I should learn to accept it, even love it, since I can’t do anything about it?

The Stoics, with Lenoir, will reply “that we must do everything in our power, first to improve ourselves morally”, then to improve the world, but where do we draw the line between what depends on me and what does not? doesn’t depend on it?

The dog tied to the cart must go with the flow and like it since he has no choice, says Epictetus. I ask: but who tied the dog? Why shouldn’t other dogs, or the men who are their masters, have the duty to revolt against those who want to tie them up? Because that’s what it is?

Stoicism is sometimes referred to as slave morality. Its determinism and its wisdom of acceptance must, in fact, make us consider it at least as a morality of the status quo. Stoicism advocates for “the ontological equality of all human beings,” but then encourages them to accept the sometimes painful fate that cosmic providence has reserved for them. It is then up to the poor to be a good happy poor man and to the rich to be a good satisfied rich man.

I claim, in the name of a metaphysics of human freedom – it is metaphysics against metaphysics, here, since the proof of freedom or its absence is impossible to do in absolute terms -, the right to revolt against this which flouts human dignity, even if this evil does not directly depend on me. I call wisdom this refusal of the defects of the cosmic order, which are often the work of humans and on which we can often act.