One morning in September 2024, Moacir Donizetti smelled a burning smell in the distance while he was checking the condition of his coffee trees. “It was desperate: seeing the flames advance, destroying our plantation and arriving 20 meters from my house,” laments this small 54-year-old Brazilian producer in Caconde, the town that produces the most coffee in this southeastern state. country.

If the start of the fire probably originated from a pile of garbage burned by a resident, its devastating and completely out of control spread is due above all to the extreme drought which affected Brazil last year. Severe heat and intermittent rainfall in places like Caconde have ripples around the world.

Coffee producer Moacir Donizetti Rossetto among burned coffee plants in Caconde, some 300 km northeast of Sao Paulo, Brazil, January 10, 2025 – Nelson ALMEIDA – Caconde (AFP)

In Tokyo, Paris or New York, coffee is expected to become more and more expensive due to the climate crisis in Brazil, the world’s largest producer and exporter of this commodity. The Donizetti family fought for four days against the flames which disfigured the bucolic landscape around their farm nestled in the middle of green hills.

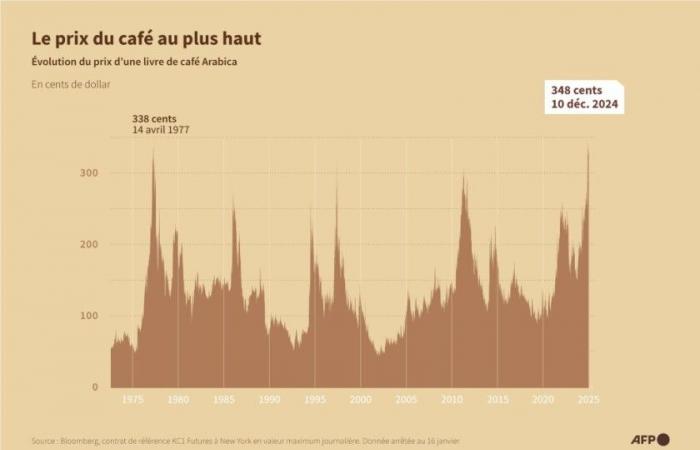

The price of coffee at its highest (2025) – Sylvie HUSSON, Paz PIZARRO – (AFP)

Devastated. Five hectares of plantations were devastated, where Moacir was supposed to harvest a third of the family’s production. “We not only lost part of this year’s harvest, but also the next ones, because we will have to wait three to four years for this land to become productive again,” laments the farmer, disappointed in the middle of the charred coffee trees.

“The weather has been too dry for about five years. Sometimes it doesn’t rain for months. It’s also much hotter, and when the flowering period arrives, the coffee is dehydrated and has difficulty resisting,” he continues. The year 2024 was the hottest on record in Brazil, where the number of forest fires had never been so high in 14 years. Most of the fires were caused by humans and their spread was aggravated by drought.

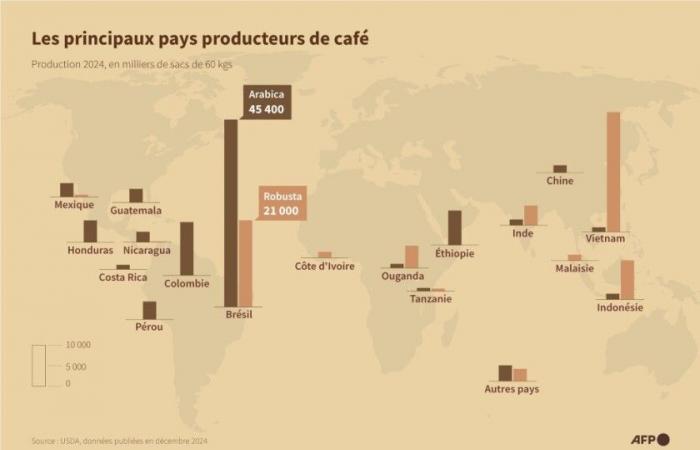

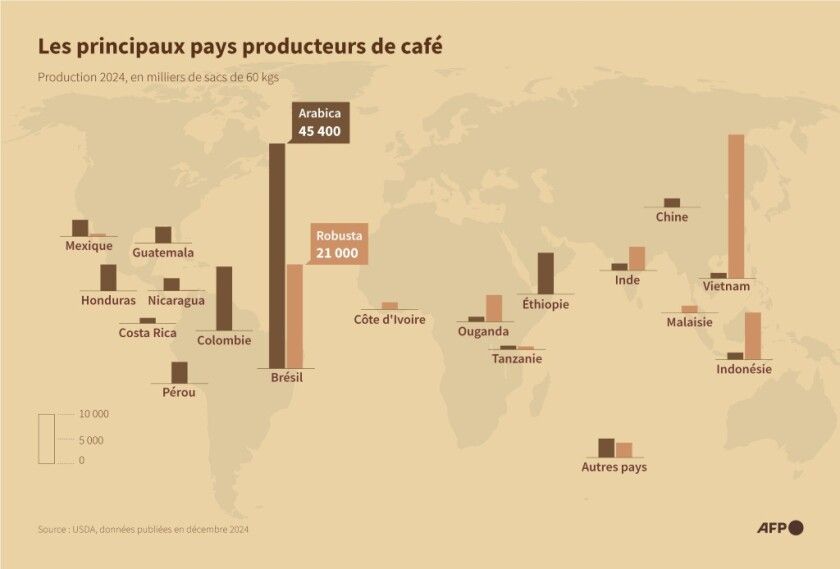

Heat and drought linked, according to experts, to climate change. More than a third of the world’s coffee is produced in Brazil, hence the strong impact of the setbacks of Brazilian farmers on prices. Up 90% by 2024, the price of Arabica, the most consumed variety, broke its 1977 record on December 10, at $3.48 per pound on the New York Stock Exchange.

The main coffee producing countries (2025) – Sylvie HUSSON, Valentina BRESCHI – (AFP)

Climate. “I have been working in this sector for 35 years and I have never experienced such a difficult situation,” says Brazilian coffee consultant Guy Carvalho. “Since the last big harvest, in 2020, we have always had climate-related problems,” he emphasizes.

According to him, the rise in prices is largely due to “frustration” with disappointing harvests four years in a row in Brazil, from 2021 to 2024, and hardly optimistic forecasts for 2025. Not to mention geopolitical factors, such as barriers customs measures promised by Donald Trump before his return to the White House or the new European regulations on products resulting from deforestation.

But some Brazilian coffee farmers are trying to adapt to the climate crisis. In Divinolandia, a town located 25 kilometers from Caconde, Sergio Lange has brought up to date an ancestral technique: planting his coffee trees in the shade of the trees to protect them from the heat. “When I was born, it was cold here, the water froze in winter,” says this 67-year-old producer.

Sergio Lange, organic coffee producer, on his coffee plantation, in Divinolandia, some 270 km northeast of Sao Paulo, Brazil, January 10, 2025 – Nelson ALMEIDA – Divinolândia (AFP)

Ancestral. “Today, this is no longer the case. With these temperatures, the current production model will soon be outdated,” he predicts. Planting coffee in the shade of trees, as it was in its original habitat in Africa, not only protects it from the heat, but also ensures that the beans ripen more slowly.

They are therefore larger and their taste is sweeter, which increases their value on the market. With around fifty other producers, Sergio Lange implemented a “regenerative coffee growing” model in 2022: the plants coexist with other species, they grow without pesticides and are irrigated naturally with spring water. “Productivity drops at the beginning, but we expect a fantastic result within four or five years,” he explains, pointing with pride to his coffee trees planted in the forest on the hillside.

Facundo FERNÁNDEZ BARRIO

© Agence France-Presse