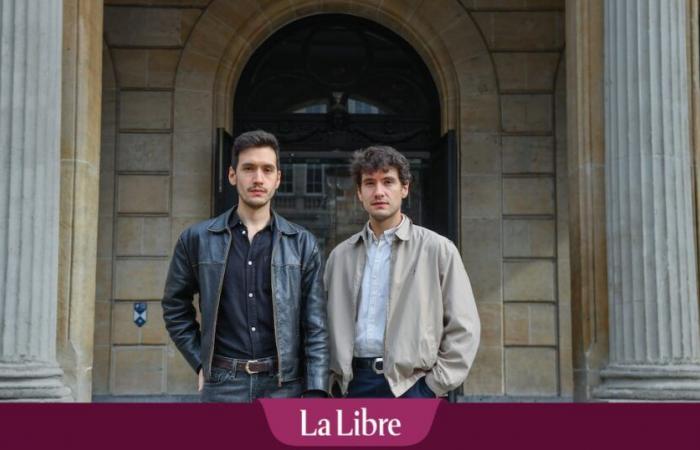

This brilliant adaptation of the 2018 Prix Goncourt by Nicolas Mathieu (see below) was unveiled last September in Competition at the 81st Venice Film Festival. It was in a garden in the Lido that we met its two young directors, Ludovic and Zoran Boukherma. Originally from Lot-et-Garonne, the two young filmmakers explained to us how, from an idea for a series produced by Hugo Sélignac and directed by Gilles Lellouche that they were to co-write, the project finally turned into a film, while Lellouche was busy preparing and filming his own film Love phewwhich also has obvious echoes with Their children after them. Just as Nicolas Mathieu’s novel resonates with the experience of the Boukherma brothers and with their genre film Teddy in 2021…

When did we move from a series project to a film?

Zoran : When there was talk of us adapting Nicolas Mathieu’s story ourselves, we very quickly said to ourselves that we had to make a film, rather than a series. The book is very social and, at the same time, it is very broad, very generous. And we wanted to transpose that into scope, on the big screen. When speaking with Nicolas Mathieu, it seemed obvious to us, because we had common cinematographic tastes.

Ludovic : He loves New Hollywood. We talked about Journey to the end of hell… We said to ourselves that we had to bring the story to the cinema. If we made a series, we told ourselves that we would have to shoot a lot, that we wouldn’t have time to take care of things.

Gilles Lellouche: “I said to myself, ‘Okay, you’re 50, it’s now or never’”

You kept the four summers structure of the novel…

Zoran : In the novel, there are four summers. But it also tells what happened between the summers and we went out of town. For example, there is a whole passage in Morocco, when Hacine is sent there by his father. There are little excursions with Steph when she studies in Paris. The first thing we said to each other was that we wanted to stay in the arena. To reinforce the idea of confinement. Anthony hears people talking about Morocco, Paris… He dreams of going to Austin. But these are all very vague places. When we were kids, in Lot-et-Garonne, there was a bit of this idea, when people went on vacation that we heard about somewhere else that we never saw. We opted for distancing ourselves from the rest of the world, as if it were impossible to access it…

gullThe end of this world that Nicolas tells very well in his words, we filmed it through the ghosts of blast furnaces…

Nicolas Mathieu’s novel won the Prix Goncourt and was very successful. Does that put pressure on your shoulders?

Ludovic : Yes, it was quite stressful.

Zoran : In the book, Nicolas makes sociological digressions of incredible accuracy. How were we going to live up to that? We considered putting in a voiceover to get a bit of his words. But very quickly, we said to ourselves that an image said so much. And we chose to trust the costumes, the sets and especially the blast furnaces, which we see almost as a character who, ultimately, tells the story of the end of the world. The end of this world that Nicolas tells very well in his words, we filmed it through the ghosts of blast furnaces…

You come from the South-West. How did you appropriate the industrial landscapes of Eastern France? You notably filmed in Hayange, the model for the fictional town of Heillange…

Ludovic : We still really found ourselves in the book. Even if it is not the same region, the problems are very similar, particularly that of confinement. Afterwards, it’s so visual. The blast furnaces are there; you just have to film them. This dead factory in the middle of the valley says it all. We also discovered that the entire city is organized by social classes; which we don’t have at all in the South-West. The town, the housing was built by the factory. There are workers’ housing estates and, depending on rank in the factory, there are different standards of housing. It’s as if all of sociology was embodied in the building… This film is still a story of social classes. In adolescence, perhaps at first, social differences seem not to exist. But, when we grow up, we are inevitably called to order and we find ourselves assigned to our class. We found it quite interesting that it was illustrated geographically in the city.

gullWhat Nicolas Mathieu says very well is that the France of the invisibles, which demonstrated during the Yellow Vests, is the majority of people.

You film the working classes without ever looking down on them, without any class contempt. How did you find this accuracy of gaze?

Zoran : We really come from the same social class as Anthony. It’s true that we really want to film her as she is. Afterwards, we don’t film them from above, but we’re not angelists either. We also show all the violence.

Ludovic : There is the idea of making a film for people. We wanted the film to be able to speak to the people we’re talking about. We wanted to make a popular film. With the use of music, somewhat grandiloquent means of cinema. We wanted to do a generous work, but also put people who are the majority at the center. What Nicolas Mathieu says very well is that the France of the invisibles, which demonstrated during the Yellow Vests, is the majority of people. We found it beautiful to make a film about people, right at their height, without leaving them by the wayside. We are talking about a social class and the people of this class, who are our parents, our families, must be able to like the film.

Paul Kircher, Marcello Mastroianni Prize for best young actor in Venice

You have a very interesting use of popular music. In the film, we hear “Saturday evening on Earth” by Cabrel, “Light the fire” by Johnny…

Ludovic : These are songs that we like. We grew up with popular films and popular music. When we listen Saturday evening on Earthit sincerely moves us. There is not an ounce of second degree. There are also social class differences in music. Springsteen and the Red Hot Chili Peppers rub shoulders with Florent Pagny and Cabrel. We find it quite beautiful that these musics can coexist, like in life. Springsteen is our absolute master, but we also find beauty in Florent Pagny or Johnny.

gullIt was the end of the working class that created a separation between the descendants of immigrants and the French.

In this film, everyone is a victim of class contempt. Even the bourgeois Stéphanie who, once at Sciences Po in Paris, passes for a redneck from Lorraine…

Zoran : We liked the idea that Steph was the best off in Heillange and that she was the only one who had a real class complex when she arrived in Paris. She’s the only one who realizes this. What we especially liked was that there was an artificial separation within the same social class. It all starts with a conflict between Anthony and Hacine, around the theft of a motorcycle. In itself, it’s just adolescent conflict, but it feels like that’s where the separation takes place. Whereas the real separation is that which exists between Anthony and Steph who, for once, belong to two different classes. We liked the idea that at the end, we say that Anthony and Hacine are not reconciled, but that they belong to the same world. It was the closure of the factory that separated them. Their fathers worked together, but they are separated, because the prospect of the factory has disappeared. It’s a bit like the idea of the end of the working class, which created a separation between the descendants of immigrants and the French. They fight among themselves or vote against each other, even though in the end, they belong to the same world.

Ludovic and Zoran Boukherma (at the time of “Teddy”): “We wanted to talk about the frustration, the anger that you can feel when you come from a disadvantaged social class”

The film and book are called “Their Children After Them”. We can imagine that these children are voting today for the National Rally… You also use the 1998 World Cup, perhaps the last moment of national reconciliation in France…

Zoran : Black-White-Beur France didn’t last very long, since there was 2002 just behind and the arrival of Le Pen in the second round… That’s why the book is anchored in the years 1990. This is really the moment when the left abandoned the demands of the working classes.

Ludovic : It is indeed the birth of the society we know today, with the rise of the RN. Not so long ago, when we were in college, the FN was a shame. In 2002, it was unthinkable for young people to vote for the FN. Twenty years later, these young people who annoyed the National Front are voting in part for the RN… And there are also many young people who have unfortunately moved to the extreme right…

Nicolas Mathieu’s book

Goncourt Prize in 2018, Their children after them (Actes Sud) by Nicolas Mathieu is a magnificent novel about what it means to live, survive and grow up in peripheries ravaged by deindustrialization. The author is interested in the working class, the lost in life, who try to make their hearts beat and their desires beat under a sky weighed down by the damage of capitalism.

The novel takes place in Lorraine, near Luxembourg, around the small imaginary town of Heillange, next to the Henne river (the hatred?). It could have happened near La Louvière or in Charleroi. The story takes place over four summers, between 1992 and 1998, for young people who are 14 years old at the beginning, 20 years old at the end. Like the end, often, of their illusions…

Accuracy and tenderness

The blast furnaces have just closed and the men are drowning their idleness in alcohol. The only events are the arrival of a giant Leclerc store and the World Cup final. Anthony, Hacine and the others hang out, smoke firecrackers, empty beer racks, listen to Nirvana and go watch topless girls by the lake.

The great strength of Nicolas Mathieu’s novel is to never be miserabilist. He recounts with remarkable accuracy and tenderness the lives of these “invisibles”, of these young people abandoned on the edge of life whose hearts remain as banners, with their rages and their desires, and who simply seek to live and love. G.Dt