Yellow, green, red… Usually, multi-colored packages are inseparable from the clusters of children walking around the townships of South Africa. Clutched in little hands like so much precious cargo, they can be spotted from afar, as long as you pay attention. Inside, chips bought for a few rands in the “spaza shops”, these tiny grocery stores which open early and close late to supply working-class neighborhoods. But snacks have become rare in little hands lately. They terrify parents since some have become mortal.

At least twenty-four children died of poisoning in a few weeks. And nearly a thousand have suffered food poisoning since September. Not everyone got sick after purchasing products from spaza shops. Some were poisoned at school or while buying snacks from street vendors. The causes are not always identified, but the shops are in the government’s sights while the psychosis spreads to the townships.

Read also | South Africa: 4,500 illegal miners trapped underground and besieged by police

Read later

On November 15, President Cyril Ramaphosa ordered the closure of businesses implicated in fatal poisonings as well as the obligation for all spaza shops to register with the authorities within twenty-one days. He also announced a wave of inspections of hygiene services across the country. Four days later, the government declared a state of national disaster.

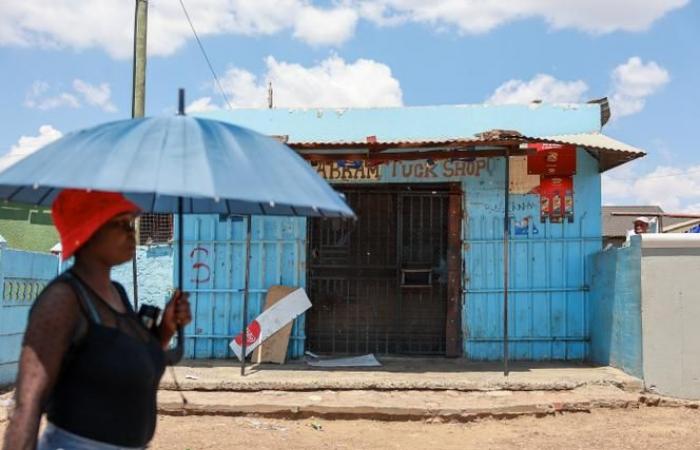

Since then, panic has spread to these small stores, which are often nothing more than dark huts made of mesh sheets leaning against private houses. Not all traders are equally worried. Coming from Ethiopia, Somalia, Pakistan or Bangladesh, foreigners are particularly feverish: since the tragedies, anti-migrant diatribes have resurfaced in a country where xenophobic violence regularly shakes the townships.

Foreigners ‘sell poison’

“I’m South African, I don’t worry”confided a trader on Friday November 22, as he left one of the centers which supervises the new administrative formalities in Soweto. He entered without problem. Calm, he nevertheless refuses to give his name on the grounds that he does not “doesn’t do politics”. The subject is sensitive. In front of the gates, a small crowd formed to filter the passage. Those unable to show a South African identity card are turned away.

“We want to protect our country from foreigners who want to declare spaza shops. We don’t want them here, they sell expired food and poison our children with their counterfeit products.”explains Sbongile Skosana, 68, grandmother of three grandchildren who are now prohibited from going near grocery stores. Next to her, a woman dressed in fatigues drives the point home: “They count their money while we count our deaths. »

Read also | From coal to renewables, South Africa faces the challenge of a “just energy transition”

Read later

Among the twenty people mobilized in front of the gates, many wore the logo of the uMkhonto we Sizwe party of former president Jacob Zuma, accused of corruption. Others proudly wear t-shirts calling for a “mass expulsion”. They belong to the Operation Dudula movement, which accuses foreigners of “steal work” South Africans and regularly organizes raids to put pressure on traders from elsewhere.

Anti-foreign sentiment extends beyond this small circle of activists. “They sell poison, they have to leave”says a grandmother in a floral dress a few kilometers away. She lives in the Naledi district of Soweto, in a street where a tragedy particularly marked the country. At the beginning of October, six children died here after buying chips in a spaza shop.

Agricultural use

The youngest was only 6 years old. “Monica, if you had seen her, she was very beautiful”murmurs the old lady, shaking her head. She also prefers not to give her name. A few dozen meters away, the shop that sold the chips was looted. In the process, residents went around the neighborhood’s spaza shops to force them to draw the curtain. Most have since reopened, but tension remains.

Stay informed

Follow us on WhatsApp

Receive the essential African news on WhatsApp with the “Monde Afrique” channel

Join

In another district of Soweto, a young Bangladeshi trader who also insists on his anonymity points to a sheaf of papers carefully arranged in folders: “I have a work permit, a certificate from the health services, all the papers are ready but they haven’t let us in for the declaration. They say they’re going to set fire to my store. It’s not the first time we’ve heard this but it’s the first time I’m scared, these people aren’t even from here, I get along very well with my neighbors”whispers the merchant, lowering his voice as soon as a customer passes a head into the store.

Read also | In South Africa, a new generation of winegrowers in search of quality

Read later

In Naledi, the cause of the poisoning was identified: terbufos, a powerful insecticide. Traces of the product were found in the children’s stomachs as well as on one of the packets of chips consumed. Theoretically, terbufos is reserved for agricultural use in South Africa but, in the townships, it is commonly sold illegally in spaza shops to fight against the rats which infest these neighborhoods.

“The problem is that it’s arranged haphazardly: they put everything in the same place, the bread next to the polish, the pesticides next to the snacks…”explains Comfort Otukile, a resident of Naledi. Eighty-four spaza shops were inspected in the area after the tragedy. Traces of terbufos were found in three of them. Sitting on steps five meters from a grocery store, Comfort Otukile nevertheless insists: “We should not put all foreigners in the same basket. »

Proof of investment of R5 million

“Here, he’s an Indian, but we don’t have a problem with him, he gives credit to the grandmothers, he’s accommodating. We told him: we will defend you, but make sure that what you sell is safe and that the store is clean. The problem is the small, cramped shops with people sleeping in them”continues this father of six children.

In his speech, President Cyril Ramaphosa highlighted the problem of rat proliferation, deploring the disastrous waste management in some municipalities. He was also careful not to stigmatize foreigners: “These products are just as likely to be sold in stores run by South Africans”he insisted.

Read also | In South Africa, environmental defenders overwhelmed by plant poaching

Read later

In the registration center in the Jabulani district of Soweto, Mduduzi Myeza, the head of the city of Johannesburg responsible for guiding traders through administrative procedures, nevertheless presents the obligation to declare stores as “an opportunity to develop the local economy”. “We do not refuse foreigners, the procedure disqualifies them by itself”he explains, listing the long list of supporting documents requested.

To register their business, foreigners must provide proof of investment of 5 million rands in the country (around 260,000 euros)… A fortune. “I just sent away a Mozambican, explaining to him that they were asking him for 5 million rands. Can you imagine? »continues the manager with a satisfied smile before concluding: “No spaza shop makes R5 million. »