FRANCOPRESSE – To reduce its expenses, the government has been modifying its internal translation system for nearly 30 years, in particular by using the private sector. But ultimately it is the French-speaking civil servants who, called upon to compensate for the consequences of this economy, pay the price.

Within federal departments and agencies, approximately 90% of documents are translated from English into French, indicates Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) in a written response to Francopresse.

If a translation is poorly done or omitted, it is the language of Molière and its speakers who suffer the consequences.

“Being bilingual added a certain workload to me, which I was very happy to assume, moreover,” confides David Lachance*, a civil servant since 2002. He says that Francophones and those who, like him, , have a high level of French and sometimes find themselves translating or revising documents.

He has seen this film a hundred times. What he has never seen is a French-speaking or bilingual person receiving financial compensation or being recognized for additional work done.

Also read: Unable to work in their language, civil servants leave

Unsatisfactory translations

If civil servants who speak French find themselves doing translation and revision it is because, according to him, since 1995, federal departments are no longer obliged to use the Translation Bureau (BT) and can turn to the private sector to make their requests.

This has greatly reduced the quality of the language and translation of documents. I have never seen an external translation as good as the one done internally. [Les traducteurs à l’interne] knew the subject better.

He explains that French-speaking civil servants are then called upon to correct unsatisfactory translations or to do them themselves when external delays are too long.

SPAC mentions, however, that public servants who are not translators, terminologists or interpreters should not be called upon to do translation.

Also read: Official languages: the Supreme Court once again asked to translate its old decisions

Nathan Prier is wary of translation software. Supposed to improve efficiency, these can affect the quality of French and require greater revision work, he believes.

Photo: Courtesy

A threat to quality

“We always hear examples [comme ça]», Confirms the president of the Canadian Association of Professional Employees (CAPE), Nathan Prier, in an interview.

He himself was asked to translate legal documents when he was an economist in the civil service.

Regarding quality, Nathan Prier shares the same observation as David Lachance: external freelancers generally cannot match BT translators.

“We should return to the BT’s mandatory service delivery model from before 1995, so that [le BT] becomes once again the sole contracting authority for translation and interpretation services and is once again fully responsible for control, quality and uniformity,” says Nathan Prier.

“If we are serious about wanting to defend the quality of translation and the quality of both official languages, and not just English, […]we really need to protect these jobs.»

Civil servants like David Lachance are not the only ones to suffer the consequences of this situation. BT translators also cash in.

A question of money

“The uneven quality of freelancers means that it is up to our members to repair external blunders. This ends up costing the Office dearly and forces our members to save the face of the institution by carrying out revisions for which they are often not fairly compensated,” CAPE expressed to the Standing Committee on Official Languages in 2016.

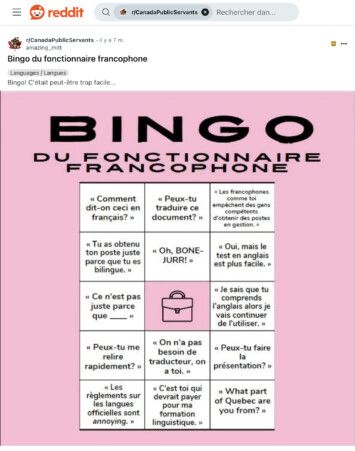

A “French-speaking civil servant bingo” has been commented on more than 150 times on the website Reddit. The translation task is included there.

Photo: Screenshot

The Association also affirmed that no translator had been hired between 2011 and 2016, leading to a loss of a third of positions at BT.

In its report, the Committee observes that when ministries resort to the private sector, it is often for a question of price.

In 2021, the professor emeritus in translation at the University of Ottawa, Jean Delisle, wrote in a memoir that “for around ten years, there has been a very clear desire to reduce expenses linked to translation as much as possible. translation. There is even talk of a reduction in the Office’s workforce of around 60%.

In its email to Francopresse, SPAC assures that the number of internal translators and the proportion of subcontracting to external translators have remained rather stable over the last eight years.

But, as Nathan Prier points out, the size of the civil service has increased “a lot”. It remains to be determined whether the BT workforce will be able to keep up with the growth in requests.

PSPC estimates that the Translation Bureau itself meets approximately 75% of the demand for translation services within the core public administration. Nearly half of these translations are passed on to subcontractors (graph below).

Also read: Budget 2024: Ottawa keeps a small place for the Francophonie

The law to the rescue?

“If everyone was bilingual like me within the public service, I think the burden on French speakers would be minimal,” David Lachance wants to believe. We should increase the ability of all civil servants to understand both languages well.”

“It seems that there is a culture within the public service where one language is favored over the other and that French is very often seen as a language of translation,” believes Raymond Théberge.

Photo: Courtesy

Asked by Francopresse about the additional tasks sometimes asked of French speakers, the Commissioner of Official Languages, Raymond Théberge, says he finds the situation “worrying”.

“This is a situation that has persisted for many years. […]. I remember when I was a young civil servant in another environment, we [m’en parlait]. What is important is to create bilingual capacity within federal institutions.”

Also read: The public service is reluctant to bilingualism, according to the commissioner’s report

According to the commissioner, creating this capacity requires compliance with section 91 of the Official Languages Act, which refers to the language requirements required for positions. Thus, French-speaking civil servants would be less required to do additional work.

“If we do a good job in assessing linguistic requirements, we will create within the unit, within the department, whatever, the necessary bilingual capacity,” he says.

This section of the Act was the subject of a study by the commissioner in 2020. He will follow up on the results in the coming weeks.

*The name has been changed for security and privacy reasons.

Type: News

News: Content based on facts, either observed and verified first-hand by the journalist or reported and verified by knowledgeable sources.

Montréal