François Audouy and Arianne Phillips, the production designer and costume designer of “A Complete Unknown,” both benefited from the pandemic- and strike-related delays that gave them more time to prep for James Mangold’s look at the first few years of Bob Dylan’s career in New York City. Not only did Mangold keep rewriting and improving the script, but the production design and costume teams had more time to figure out how to re-create the time, place and feel of a world that hasn’t existed for 60 years — though not through slavish imitation.

“I went into production after four years of marinating and learning about Bob,” Phillips said. “We’re not making a documentary, but we’re trying to excavate the essence of Dylan. My thing is to understand the research as much as possible and then be able to improvise. Once I understood the enigma of Bob Dylan, who created his own mythology, that gave me permission as a costume designer to be true to his spirit.”

For Phillips, the keys to Dylan’s look in the four years covered by the film, 1961 to 1965, were in a few of his visual trademarks. “His boots, his hair and his denim were really my gravitas for showing that evolution over those tight four years,” she said. “It was very clear to me that this was a unique opportunity to collaborate with hair and makeup, because really the audience is going to understand this character’s evolution through his hair and his dress. And that was really our directive. When I read the script, I thought, I can really help the audience on this journey – that’s my job on this movie. So early on we broke down the beats of our film in terms of his style evolution. There’s ’61, ’62, ’63, ’64, and then, boom‘65.”

For Audouy, the problem was location, location, location. “Greenwich Village plays a major part in this movie,” he said. “But if you go to Greenwich Village today, you can see shadows of what it must have been like, but it’s not the same. There are some streets that are still quiet and romantic, but it’s been taken over by tattoo parlors and head shops and bars, and it’s become extremely touristy.

“Like McDougall Street – with all the money in the world, you couldn’t turn McDougall Street into McDougall Street. It’s so different. A lot of my work is taking down things and removing things before you can even start adding things. I would still be there prepping McDougall Street if we shot on McDougall Street.”

Some spaces were re-created as exactly as possible: The Columbia Records recording studio was duplicated from 400 photos in the Columbia archive, and the 4th St. apartment Dylan shared with the girlfriend played by Elle Fanning was painstakingly rebuilt based on the original negatives from photo shoots that took place there. But in other cases, being precise wasn’t the goal. “You don’t re-create exactly every interior and exterior—you can’t, and it’s not the point,” Audouy said. “The point is to re-create what it felt like. I just kept thinking of Bob’s line [from ‘Like a Rolling Stone’]: ‘How does it feel?’”

Production Design Sketch: Diner, Greenwich Village

“I can’t tell you how difficult it is to find early 1960s New York,” Audouy said. “It doesn’t exist. Everything had to be created.” Most of the re-creation, including this diner that was the location of an early date between Dylan (Timothée Chalmamet) and Sylvie Russo (Fanning), took place in the area between Hoboken and Jersey City across the river from Manhattan, an area the production team dubbed “the Jersey Hub.”

Production Design Sketch: Interior, Gerdes Folk City

The interior of Gerdes Folk City, a club frequented by Dylan, was built in an Elks Lodge on Washington St. in Hoboken. “The space was like a time capsule that hadn’t changed much in the last 50 years,” Audouy said. “And in the basement was another set that was the Gaslight Café, with a whole different look. It was kind of like a twofer.”

Production Design Sketch: Exterior, Greenwich Village

To look for locations that would work as Greenwich Village, Audouy would bicycle through New Jersey. “I would geotag my bike and zigzag every single street,” he said. “I did it over two weekends, riding down every street from North Hoboken all the way down to South Jersey City, just to make sure that I had combed that part of New Jersey for locations.” Among the finds: a corner joint that they turned into the bar McAnn’s, where Dylan and his new pal Bobby Neuwirth end up in a brawl.

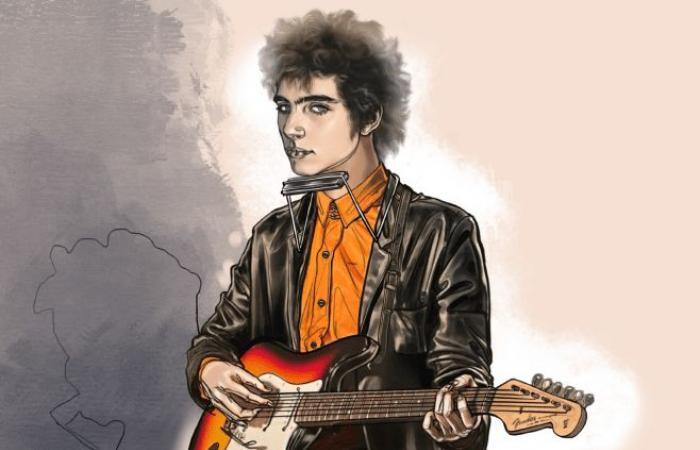

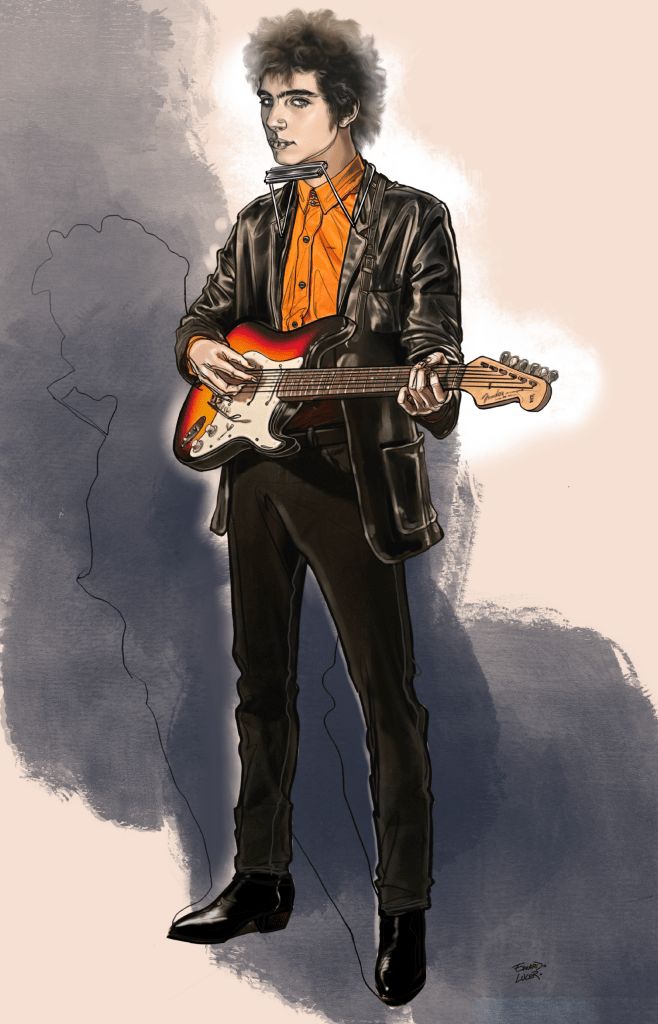

Costume Design Sketch: Bob Dylan 1965

Chalamet had almost 70 costume changes as Dylan. His outfits in 1965, like the one shown here, were a dramatic departure from his earlier, more rural style. “Bob always wore boots,” Phillips said. “In the beginning it was work boots, then in the mid ’60s it was a cowboy boot and a rough-cut boot, and then in ’65 it was the Chelsea boot.” Dylan’s jeans were also crucial: 501s early on, less familiar models later. Her contacts at Levi’s were able to identify Dylan’s mid-’60s jeans: “They were called Super Slims. We could not source or find them anywhere, so Levi’s generously, kindly and happily remade them for us.”

Costume Design Sketch: Sylvie Russo

Elle Fanning’s Sylvie, who’s seen in about two dozen outfits, was based on Dylan’s early-’60s girlfriend, Suze Rotolo. “When you have 20 or more costume changes for a character, I like to have real vintage pieces mixed in,” Phillips said. “First of all, it’s aged already. Phedon Papamichael is a brilliant cinematographer, and the way the film is lit is quite saturated. So we had to age the clothes twice as much as normal because on film everything gets clean and beautiful.”

A version of this story first appeared in the Below-the-Line Issue of TheWrap’s awards magazine. Read more from the issue here.