Richard without embarrassment

Since the masterful scenario of Taxi Driver, we know Paul Schrader’s taste for his characters on the edge of the abyssattracted by the whirlwind of the abyss through their captivating voiceover. With each new film, a piece of the puzzle is added to better understand a filmmaker who has always spoken about his own darkness. A typically human darkness, constitutive of our essence and which we must always seek to combat.

A sign of the passing of time, the existential solitude of Schraderian souls is increasingly haunted by death. The ticking of the clock advances, and is accompanied by an attempt at salvation, magnificently worked in the director’s latest trilogy: On the path to redemption, The Card Counter et Master Gardener.

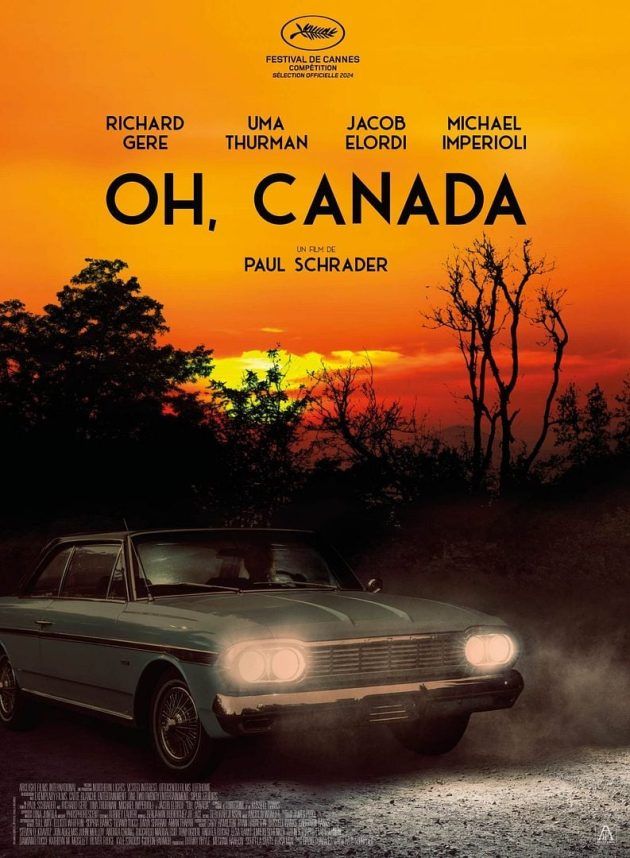

Oh, Canada is part of this continuity, while leading Schrader to renew (a little) a formula which was beginning to run out of steam. This time, we follow Leonard Fife (Richard Gere and Jacob Elordi), a committed documentary filmmaker suffering from an incurable illness. While his memory plays tricks on him, he agrees to retrace his life through a filmed interviewin a set of more or less exact and ambiguous memories.

Certainly, the recited diary of his anti-heroes is only replaced by another device, but this relationship with the image has more than ever a religious dimension, worthy of a confessional that Schrader transforms into a subdued mental space, a receptacle of formats changing images.

“This is my last prayer, and we don’t lie when we pray”Leonard Fife solemnly declares during filming. The respected author, author of controversial political works, knows he is on the brink of the abyss, and wants to ensure absolution. If this American fled to Canada to avoid being drafted during the Vietnam War, this act considered courageous in reality hides the permanent headlong flight of a man with his life, his wives, his children.

On the road

In this chaos of movement, of comings and goings and doubts, Schrader attaches himself to scraps of life, to images which mix in the foggy head of his protagonist. We can criticize the director for wallowing a little in this clashing structure (especially towards the end), but the verbal dynamics of his cinema have rarely been so supported by the power of his editing.

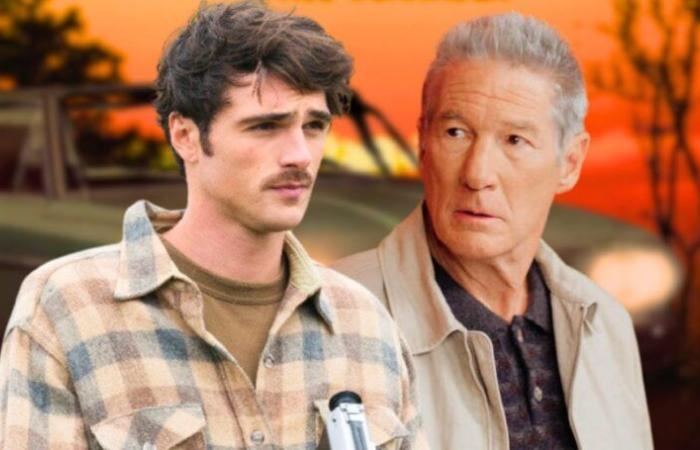

In one connection of this kaleidoscope of a life, the body of Richard Gere can become that of Jacob Elordi, or even makes different generations coexist in the same plane. This heavy feeling of time also allows the actors to get the most out of their performance. Uma Thurman regularly upsets in her restraint, while Gere develops an unsuspected palette with each close-upwith each unsaid revealed. In this stripping of leaves, coupled with the vulnerability of its protagonist, Oh, Canada touches the heart, and intelligently uses its star’s sex symbol background to film with concern the progressive dysfunctions of an aging body.

It must be admitted that the heterogeneity of the whole is tiring at times (notably when the story forces its breaks in filming), but it is also in this break that Schrader surprises the most. We could have expected that the film’s discourse would “separate the man from the artist”, or seek to justify the acts of the past on the altar of creation.

On the contrary, the filmmaker appears much more definitive. Fife knows that his work will survive him, and that he cannot hide behind it to hope for inner peace. His art is ultimately very little mentioned during the interview, because he must confront his inner demons, and the boundaries that he has chosen to cross, literally and figuratively.