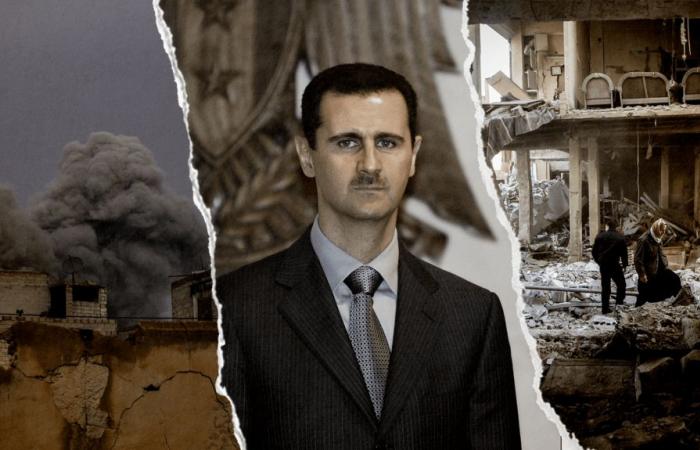

A breath of hope for the victims of the “butcher of Damascus”. The offensive by rebel groups led by the Islamists put an end, on Sunday, December 8, to half a century of unchallenged rule by the Assad clan over Syria. The deposed Syrian dictator, Bashar al-Assad, succeeded his father, Hafez, in 2000 and resumed his methods to subdue the regime's opponents. The images of the liberation of Saydnaya prison, located in the Syrian capital, reminded the whole world of the horror experienced by detainees, cut off from the world, tortured, starved, thirsty and killed. The repression of the revolution, which began in 2011, “caused more than 400,000 victims and pushed nearly a quarter of the population into exile”recalled the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Bashar al-Assad was forced to flee and a transitional government, supported by radical Islamists from the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group, was formed. The country's new leaders have promised to bring justice to the victims, ensuring that those responsible for the torture of detainees will be punished. “We emphasize the importance of holding the Assad regime accountable for its crimes”insisted the G7 member countries in a joint declaration. Abuses and bombings against civilians, the use of chemical weapons or the use of torture are among the war crimes and crimes against humanity of which the regime is accused. But can Bashar al-Assad even be tried?

“There are three possible mechanisms”explains Caroline Brandao, teacher-researcher in humanitarian law at Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne University. First, at the national level, “des jurisdictions could be set up”she underlines, because the abuses were committed in Syria, by and against mainly Syrians. For Clémence Bectarte, a lawyer at the Paris bar specializing in international criminal law, Syrian justice is even “natural and logical jurisdiction”. But everything needs to be rebuilt in this country which experienced dictatorship for more than fifty years. “This requires a democratic transition, the establishment of a rule of law, a new Constitution, because Syria has not yet integrated international crimes into its laws”recalls the lawyer.

“Today, crimes against humanity do not exist in Syrian law.”

Clémence Bectarte, lawyer specializing in international criminal lawat franceinfo

The second option is recourse to the International Criminal Court (ICC), competent for “conduct investigations, prosecute and try accused persons” particularly war crimes, it is written on its site (PDF). Except that Syria is not one of the 124 states which have ratified the Rome Statute, the foundation of the institution. The country does not recognize the International Criminal Court, “she has no jurisdiction over crimes committed in this territory and its citizens”says its spokesperson Fadi El Abdallah to franceinfo.

For the court to be able to intervene, it would be necessary “that Syria accepts the jurisdiction of the Court with retroactive effect, or that the UN Security Council submits a request for an investigation to the ICC”he continues. As it stands, the first option is uncertain and the second is improbable. More than once, United Nations member states have attempted to refer the Syrian issue to the ICC. But Russia, with the support of China, blocked the initiative each time by exercising its right of veto.

There remains the third way, that of the States. “There are victims of other nationalities. Their country is competent to judge Bashar al-Assad”assures Mathilde Philip-Gay, professor of law at Jean-Moulin Lyon 3 University and author of Can we judge Putin?. French justice was thus able to issue an arrest warrant targeting the dictator for the chemical attacks committed in Eastern Ghouta in 2013, which left more than 1,000 dead. An NGO had filed a complaint for “war crimes” and “crimes against humanity” and Franco-Syrian victims had joined as civil parties.

Some States have even included universal jurisdiction in their Penal Code: they can judge offenses committed by foreigners, even when the victims have no connection with the country. And Bashar al-Assad now being a deposed president, “the question of personal immunity [accordée aux chefs d’Etat] will no longer arise”help Caroline Brandao.

But the “butcher of Damascus” fled and found refuge with his Russian ally, who granted him asylum. “It is very unlikely that Russia [fidèle soutien de la Syrie] agrees to deliver Bashar al-Assad to any jurisdiction”believes Clémence Bectarte, while Vladimir Putin is also the subject of an arrest warrant for a war crime: the “illegal deportation” of Ukrainian children.

This protection could, however, collapse, envisages Mathilde Philip-Gay, who imagines three scenarios: “If an outside army invades Russia and arrests the two men if the Syrian leader is let go by Moscow and leaves Russian territory; or if the person who succeeds Vladimir Putin decides to hand them over to the international community.” Slobodan Milosevic found himself in this third situation. In 2001, the former Serbian president was handed over to international justice by the government that succeeded him. He was convicted for his crimes against humanity during the conflicts that tore apart the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

“The time for justice can be extremely long”concedes Caroline Brandao. Emmanuel Daoud, registered on the list of lawyers at the International Criminal Court (ICC), is nevertheless confident about the possible trial of Bashar al-Assad: “I think he will be judged one day. And this is not wishful thinking, it is not a fad, it is not an illusion. It's very concrete, rational”he explained on franceinfo. This certainty is reinforced by the fall of the regime, which suggests the possibility for investigators to access material evidence of these crimes. “The situation is comparable to that of Germany in 1945, when the Nazis fell. There are, suddenly, a huge number of accessible documents”illustrates Nerma Jelacic, of the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), an NGO which has been collecting evidence since 2011.

“For the first time in fifty years, investigators can go into the field to recover evidence.”

Clémence Bectarte, lawyerat franceinfo

The day after the capture of Damascus by combatants, NGOs and jurists from around the world insisted on the issue of preserving documents, photos, registers, etc. “Evidence is not social networks. It must be collected and preserved under certain conditions”points out Mathilde Philip-Gay. Many crimes have been documented in recent years, notably thanks to “Caesar”, this anonymous officer who photographed the martyred bodies of thousands of people executed in Syrian prisons. “But we must have everything, on all crimes, because each victim counts”insists the law professor.

They are also essential to find all the other members of the regime who participated in the abuses. “In international humanitarian law, we will judge the people who made decisions, but also those who implemented them”recalls Caroline Brandao. A former head of a Damascus prison, for example, was indicted in the United States on Friday for acts of torture. “Many members of the regime have already fled to neighboring countries and will certainly try to get closer to Europe. We must therefore go through the documents to identify and apprehend them as quickly as possible”estime Nerma Jelacic.

Even once senior officials have been identified, “It will be a long process, regardless of the jurisdiction that prosecutes themrecognizes Clémence Bectarte. Extradition requests or arrest warrants will be required so that they can be tried and can answer the charges against them.”. But for the lawyer, as for all the observers interviewed by franceinfo, the priority is that the Syrians have their say: “It is they who must decide the model of justice they wish to put in place. The need for justice and truth is extremely important.”