“Imagine a patient who wants to become pregnant and who is pregnant with a precancer or cancer. It’s a terrible shock,” says obstetrician-gynecologist Philippe Sauthier, from the University of Montreal Hospital Center (CHUM).

Elisabeth Lussier-Arpin can attest to this. I had never heard of that

she recalls, about the moment when, at age 29, she learned that the pregnancy she thought she had for nearly two months, her first, was actually a tumor.

This is called a molar pregnancy. It is an abnormal pregnancy where, very shortly after fertilization, the embryo stops developing and where the cells which are intended to give rise to the future placenta proliferate excessively.

describes geneticist Rima Slim.

His team at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center (MUHC) is studying the genetic origins of these placental tumors, also called hydatidiform moles, which affect approximately one in 600 pregnancies.

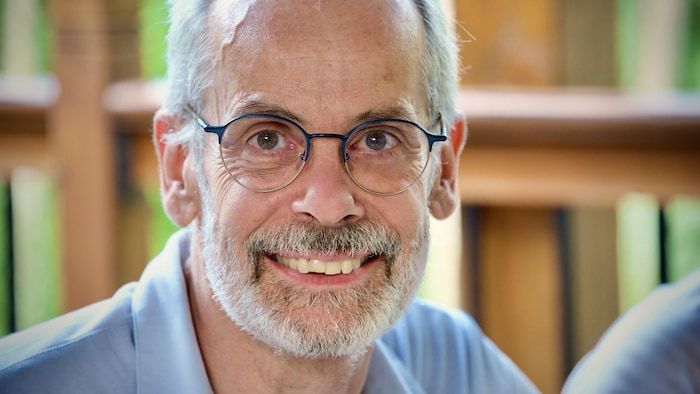

Open in full screen mode

Rima Slim is a geneticist at the McGill University Health Center.

Photo : Rima Slim

Rima Slim and her colleagues have just published a study in the Journal of Clinical Investigation in which they identify six new genes linked to these cases of rare and little-known cancers.

The classic case is a 27 or 28 year old woman who wants to become pregnant and who becomes pregnant. No problem, nothing special, no family history most of the time, and then she starts bleeding

evokes the obstetrician-gynecologist Philippe Sauthier, who collaborated in the study.

She goes to see her doctor who will do an ultrasound, who will look and who says: “Weird, there is no embryo and the uterus is full of strange things.” This is where we suspect a mole

explains this specialist in trophoblastic diseases, a term which encompasses the different types of placental cancers.

Although placental tumors are benign most of the time, they can become malignant in up to 15% of cases and require treatments such as chemotherapy. In the most severe cases, they can even cause metastases to other organs.

This was the case of Elisabeth Lussier-Arpin. The mole turned out to be aggressive and metastasized to his lungs. This was followed by three rounds of chemotherapy treatments to overcome it last summer.

As this very rarely happens in Quebec, my oncologist was in discussions with people in England and Ontario to establish the protocol.

In theory, I’m cured

she rejoices today, although with a certain caution. One aspect that is very hard is not being able to try to have children for two years. Usually, if the cancer has to come back, it is during this time

she explains.

Open in full screen mode

Elisabeth Lussier-Arpin developed a molar pregnancy.

Photo: Elisabeth Lussier-Arpin

Recurrent molar pregnancies

Even if the risk is tiny, it is not impossible that a new pregnancy also turns out to be a mole.

It happens that molar pregnancies are recurrent, or that they occur in several members of the same family. These extreme and very rare cases are of particular interest to researcher Rima Slim, who is studying them to better understand the mechanisms causing these diseases.

In 2006, the researcher identified a first gene, involved in 55% of cases of repeat molar pregnancies. When the patient has mutations in this gene, she is healthy, she has no problems, she specifies. She only consults on the day she is trying to conceive and each of her pregnancies ends up being a molar pregnancy.

Even if these genetic factors concern a very small part of these diseases, it is an important answer to the questions of women who suffer from them. These patients can be tested and then, instead of doing in vitro fertilization with their own eggs, they can use eggs from a healthy donor. At that time, it is possible for them to have a normal pregnancy

argues the geneticist.

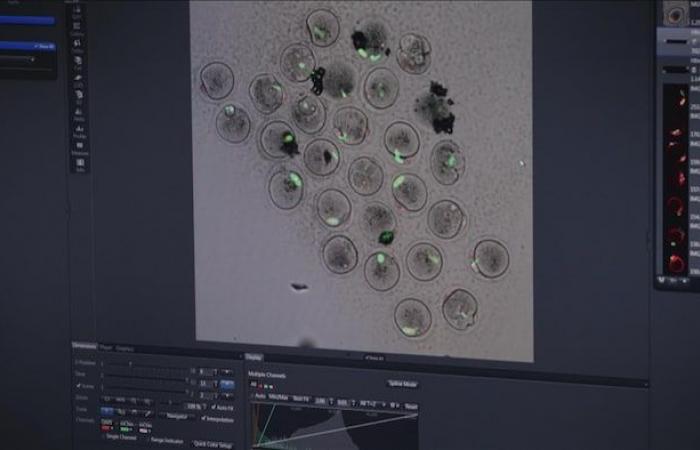

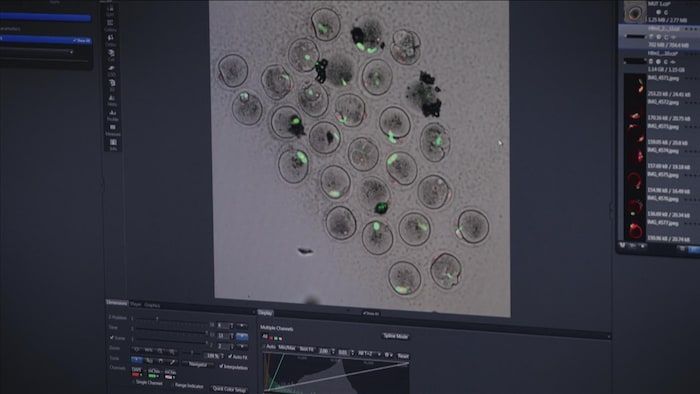

Open in full screen mode

The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center has developed expertise in the field of molar pregnancies.

Photo : -

Since the discovery of this gene, his team has identified three others linked to molar pregnancies in 2018, then another six which are the subject of this new study. Genes which essentially play a role in the formation of reproductive cells.

In women, the cells that form the eggs, called oocytes, divide by sharing their 46 chromosomes into two sets of 23. However, in oocytes where these genes are defective, this process is disrupted.

Chromosomes, spindles [qui permettent leur migration]everything is expelled outside the cell

shows Teruko Taketo on a screen. The researcher in reproductive biology at McGill University collaborates on the work of Rima Slim and her colleagues.

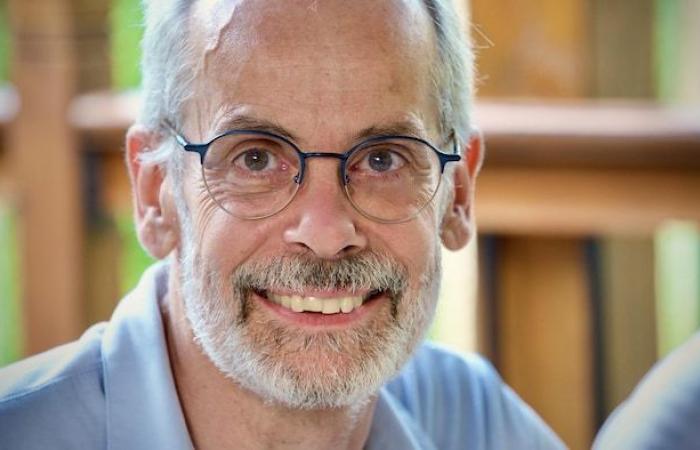

Open in full screen mode

Teruko Taketo is a researcher in reproductive biology at McGill University.

Photo : -

His team filmed the division of mouse oocytes in which one of the identified genes had been mutated. In these images, we can see the chromosomes coming out of the cells during their formation. Imagine that this type of oocyte is fertilized. No maternal chromosome would contribute [au fruit de cette fécondation]

she said.

However, this is what seems to happen in a good number of molar pregnancies, where only paternal DNA is present. The fertilization of an egg by one – or in some cases several – sperm does indeed take place, but somewhere along the way, the mother’s DNA disappears.

Open in full screen mode

Oocytes from mutated mice lose their chromosomes.

Photo : -

Unravel the mystery

The phenomenon has been known since the 1970s, but it was only in 2018 that the team observed the mechanism for the first time, in mice. We solved a 40-year-old scientific mystery

underlines Rima Slim.

Rima allows me to understand the underlying mechanisms and I can refer patients to her

enthuses Philippe Sauthier, who contributed to this work through the Quebec Trophoblastic Disease Network (RMTQ), which he launched in 2009. This unique structure in the country is intended to improve the management of patients with these rare cancers.

Open in full screen mode

Philippe Sauthier is an obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Montreal Hospital Center.

Photo: Philippe Sauthier

A trophoblastic disease, a gynecologist will see one every three or four years. Me, in the last 15 years, I have seen five a week

evokes the specialist in gynecological oncology to illustrate the importance of sharing this expertise.

The RMTQ also offers to match patients with women who have had similar experiences. The first thing they all tell us: I really felt like I was the only one in the world who had this.

he notes.

It’s so rare that there isn’t a comforting reaction, in the sense that no one has been through it, it’s super rare, there aren’t that many studies

evokes Elisabeth Lussier-Arpin, herself torn between the desire to bear witness to her experience and the fear of causing anxiety around this little-known phenomenon.

It’s still a sad subject, it distresses the women around me who I see trying to get pregnant. We need to educate people about this disease, but at the same time, we don’t want to scare them.

she concludes.

The report by journalist Gaëlle Lussiaà-Berdou and director Hélène Morin is presented on the show Discovery Sunday at 6:30 p.m. (EST) on ICI TÉLÉ and Saturday at 6:30 p.m. on ICI RDI. It is also available for catch-up on the website ICI Tou.tv (New window)