By signing the global agreement on biodiversity in Montreal in 2022, the world’s countries have committed to protecting at least 30% of land and inland waters, as well as 30% of marine and coastal areas.

This is a monumental challenge, considering what we have managed to protect so far.

The latest figures released during the United Nations conference on biodiversity in Cali, COP16, remind us of all the work that remains to be done. According to the report Protected Planetpublished on October 28 by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), we must redouble our efforts: the surface area of protected areas must double on land and triple at sea within five years.

To give an order of magnitude, it would still be necessary to protect the equivalent of the surface area of Russia for land and the equivalent of the Indian Ocean for maritime areas.

In fact, barely 17.6% of land and 8.4% of seas are now protected on a global scale. Canada and Quebec are not left out. They have protected 13% and 17% of the land and barely 10% of the sea, respectively.

As we can see, there is a long way to go.

Even if we managed to do it, even if a third of the planet was preserved, does that mean that the problem is solved? That we no longer have to worry about the remaining 70%?

Of course not.

Open in full screen mode

Aerial view of an agricultural plot and degraded forest in the Guaviare department, Colombia.

Photo : AFP / RAUL ARBOLEDA

Focusing only on the 30% could prove, at least in part, to be a false good idea. Establishing protected areas is probably the easiest part of the entire task facing us to protect the planet’s ecosystems.

Let’s be clear: it’s not that it’s easy, but it may be less complicated. Easier, because better defined. There is a precise target to reach, there is a global agreement which gives political legitimacy to decision-makers to act, there are tools developed by scientists to do so, and there is the motivation to be able to show to voters and the rest of the world that we have achieved our targets.

This is not the case with the rest of the territories. However, the fact that they are not designated as protected does not mean that it is permissible to ransack them. In any case, no government or industry would benefit from doing so. Our economies depend largely on nature and the services that ecosystems provide us.

To preserve the remaining 70%, we must face a much more complex reality, politically and economically.

What we eat

It is an ethical and philosophical question

the Filipino Oliver Oliveros told me, during a meeting at COP16 in Cali. He coordinates the Agroecology Coalitionan organization based in Rome and established with the support of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Open in full screen mode

The Filipino Olivier Oliveros is coordinator of the Agroecology Coalition and an expert in rural development.

Photo: - / Étienne Leblanc

What does it mean to feed the planet? Are we only producing what we really need?

he asks himself. Above all, it is about thinking and acting to transform the way we produce and consume the food that nourishes us.

Indeed, according to the most recent report of theIPBES – the equivalent of IPCC for biodiversity issues – among the five main causes accelerating the loss of nature, the major factor of degradation is the way humanity uses land and the sea. The conversion of land covers such as forests or wetlands for agricultural and urban purposes is to be pointed out.

In fact, agricultural expansion remains the main driver of deforestation, forest degradation and loss of forest biodiversity.

According to a report from UNEPglobal food systems are key drivers of biodiversity loss (New window)with agriculture alone the perceived threat to more than 85% of the 28,000 species threatened with extinction.

Tackling the global agricultural system is not an easy task, but in view of the scientific data transmitted to us every day by experts, it is one of the main projects to be launched to preserve the 70% of the remaining territories.

Open in full screen mode

Aerial view of goats in Bahia State, Brazil. This region has lost almost 40% of its traditional agricultural territory, with land now used for intensive agriculture.

Photo : AFP / PABLO PORCIUNCULA

Value systems

Produce, produce, produce! Why always produce more?

cast Oliver Oliveros.

If we want territories outside protected areas to remain sources of well-being for the population, we must work to change our system of thought and our system of values, we must think about economic development with a holistic approach.

he said.

Great program. But it is clear that the recipe used until now has not really worked.

Protecting the remaining 70% therefore forces us to question the economic system that feeds us, and a way of life that does not seem sustainable in the long term, at least that which we find in industrialized countries and increasingly in emerging economies.

This applies to the protection of nature which contributes to our well-being, but also to the climatic balance of the planet.

The task, we can understand, is beyond us. These days, between concern for the end of the month and concern for the end of the world, the former often wins. This is a normal cognitive reaction.

Redirect resources

According to many experts, including Oliver Oliveros, protecting the 70% of unprotected territories does not necessarily require renunciation or great sacrifices, but rather the acceptance of being able to redirect resources.

For example, many scientists say that we need to support more small-scale agriculture, which is kinder to the environment. The same goes for organic farming (which uses fewer pesticides and chemical fertilizers) or for agroecology (which requires the presence of a minimum of biological diversity on the farm and which promotes the richness of ecosystems in an agricultural context).

Open in full screen mode

The Pura Vida agroecological farm, in the village of Andalucía, 130 kilometers north of Cali.

Photo: - / Étienne Leblanc

Does this mean that we must collect this money from citizens’ pockets? Not at all, the World Bank tells us (New window). We just need to channel the money better.

The world’s governments currently provide more than $1.25 trillion per year in subsidies to activities harmful to biological diversity, such as intensive agriculture or the fossil fuel industry.

The global agreement on biodiversity, signed in Montreal in 2022, asks signatory governments to reduce subsidies harmful to nature by 500 billion per year by 2030 (target 18 (New window)), money that could be channeled towards agricultural activities that are kinder to the environment.

Another example is our diet. It is not a question of eating less, but of replacing our meat consumption with plant proteins that are less harmful to the land and often more locally produced. Meat production requires intensive agriculture to produce livestock feed (soybeans, corn) and high use of water.

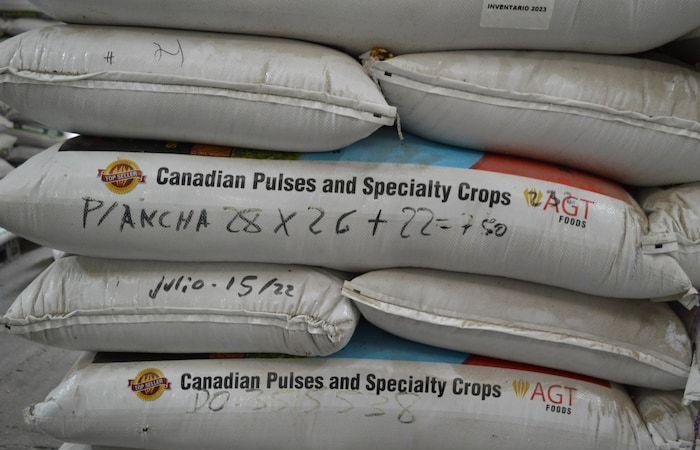

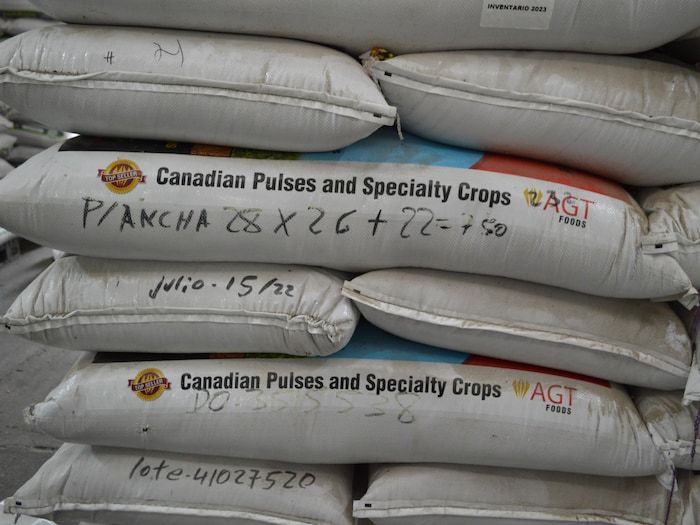

Canada is the world’s largest producer of lentils, and a major producer of chickpeas. How come these legumes are not more part of our diet?

Open in full screen mode

At the CAVASA Food Distribution Center in Cali, there are many bags of beans and lentils from Canada.

Photo: - / Victor Letelier

There still needs to be awareness raising to encourage us to change our behavior, and the vegetarian alternative to be attractive to the majority of citizens.

Did you know that three-quarters of our food on the planet depends on only 12 plants (wheat, rice, beans, etc.) and five animal species? This food homogenization is driven by an industry that wants to make life easier. Local and indigenous communities around the world have developed thousands of foods over the centuries, but their food culture is threatened by environmental degradation and an economic system that does not favor them.

We don’t know it, but there are hundreds of products that we could eat to replace meat, to which we don’t have access.

This is without mentioning food waste. Globally, approximately 13% of food produced is lost between harvest and retail, and 19% of total food production is wasted in households, food service and retail.

Acting on this problem is also a way to reduce pressure on agriculture, and therefore on the climate and biodiversity.

All these possible solutions will not develop without political will, without the support of governments for alternatives to activities which degrade territories.

The question is above all not to choose between protecting 30% of the planet’s lands and seas and letting the rest deteriorate without taking action.

It would be a trap, to the detriment of our well-being.