After two days of difficult, emotional and heated conversations, Canada’s First Nations leaders have rejected the proposed agreement to reform the indigenous child welfare system worth $47.8 billion over 10 years.

By voting against the first proposed resolution, which supported the agreement, the majority of voting leaders in fact rejected the draft agreement proposed by Ottawa, the Assembly of First Nations, Ontario chiefs and the Nishnawbe Aski Nation.

267 chiefs and representatives of First Nations in Canada out of 414 voted against.

More than 1,000 chiefs, representatives and other members of the First Nations were registered to attend in person or online these two days of decisive discussions on this agreement which aims to end discrimination against indigenous children.

British Columbia, which has 202 Indigenous communities, and Ontario, which has 134, are the two provinces that had the most weight, as they represent more than half of Canada’s First Nations.

Succession d’opinions au micro

Shortly before the vote, questions continued to come at the microphone and the discussions were heated, each camp putting forward its positions, whether in favor or against the agreement at the current stage.

Open in full screen mode

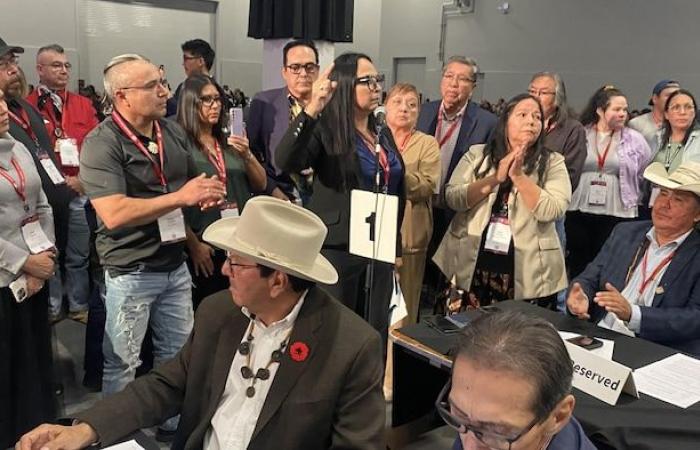

Mary Teegee, from the Takla Lake First Nation, in British Columbia, and executive director of the Carrier Sekani Family Services Aboriginal family center, addressed the assembly asking them not to vote in favor of this agreement. Several chefs came to support her.

Photo: - / Marie-Laure Josselin

The national leader, who was relatively discreet while listening to the debates, came to say a few words to remind us that this case has been before the courts since 2007 and that it took many, many years and many people to get things done

.

Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak still hoped find a common solution, because it’s too much money for this agreement to simply be taken off the table and left to the courts to resolve this issue, which could take a few more years

without forgetting that in the event of refusal, it could not guarantee obtaining a better agreement from a possible next conservative government.

Open in full screen mode

National Leader Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak sought to reassure the gathering, saying the agreement would put power back in the hands of chiefs and communities when it comes to child protection.

Photo: - / Marie-Laure Josselin

Early in the afternoon, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, Cindy Blackstock, who presented with theAPN a complaint against the Canadian government before the Canadian Human Rights Commission in February 2007, which led to this legal saga and this proposed agreement, reiterated his fears.

The various points of divergence that she has already raised are notably linked to the facts that this agreement does not end the discrimination of indigenous children placed in the protection system, that there are governance problems and that Canada is trying to escape the legal obligations imposed by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal.

This decision you make is important and I respect each individual decision

she said by way of conclusion in a silent assembly.

From the bottom of my heart, I honestly say, I cannot recommend this deal

she said.

She pleaded in favor of continuing the fight and returning to the working table in order to obtain a better agreement. His speech ended with loud applause.

Open in full screen mode

Cindy Blackstock clearly said she could not approve this agreement while National Leader Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak (to her right) listened to her arguments.

Photo: - / Marie-Laure Josselin

These two days of difficult discussions concluded with the visit of Phil Fontaine, the former chief of the Assembly of First Nations. He was at the head of this organization which represents the more than 630 First Nations communities in the country when this legal saga began in 2007. Using examples of previous cases that he led and won, he recalled that It’s a constant battle.

We are stronger when we are together. We become weaker when we are divided. I hope and pray that when we leave this assembly, we will be united.

The leaders arrived in Calgary Wednesday morning in dispersed ranks to discuss and vote on the $47.8 billion deal over 10 years. They spent two lively days. The national leader had warned that the conversations were going to be difficult, because several had already announced that they disagreed with the agreement.

One of the big points of contention was governance. Indeed, a reform implementation committee, made up of members appointed by stakeholders, provided for in the draft agreement, made many leaders cringe who feel they do not have a voice at the table. Modifications were proposed to include a representative from each region.

The other big questions concern the funding mechanism and the fact that if the agreement goes through and is approved by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal (CHRT), it will end the legal orders of the TCDP who hold Canada responsible for discrimination against First Nations children.

Open in full screen mode

Wilfred King, Chief of the Kiashke Zaaging Anishinaabek (Gull Bay) Nation in Ontario, came to support the agreement and say it was time to move forward for the children.

Photo: - / Marie-Laure Josselin

The agreement should allow First Nations to play a leading role in the provision of services to children, especially in prevention, with more funding.

This $47.8 billion agreement is in addition to more than $23 billion in compensation for approximately 300,000 children and their loved ones harmed by the youth protection system.