In Africa, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has become a bigger killer than malaria, HIV or tuberculosis, which were previously the three leading causes of death on the continent. In 2019, AMR was associated with an estimated 55,000 deaths from HIV and 30,000 from malaria. According to a study published in The Lancetit is estimated that in 2019, bacterial AMR was responsible for 1.05 million deaths, including 250,000 directly linked to this resistance in the WHO African region.

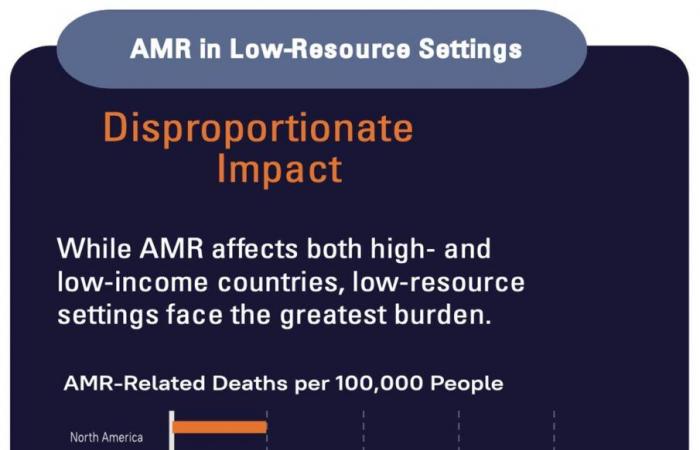

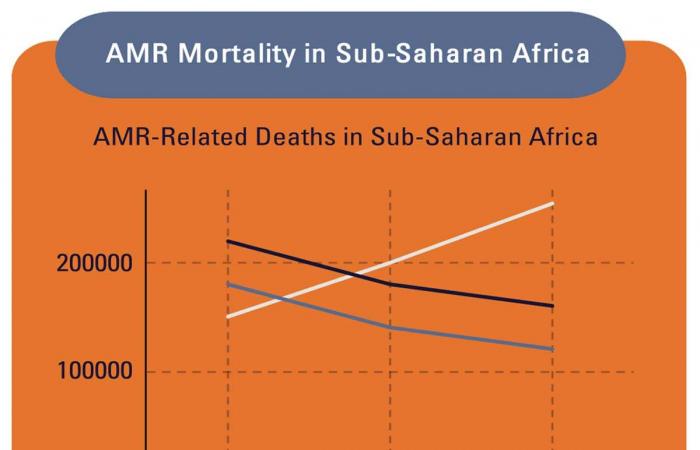

Although AMR is a global crisis, sub-Saharan Africa bears the greatest burden, with 23.7 deaths per 100,000 population, compared to 5 per 100,000 in North America, for example. It is also observed that AMR-related deaths continue to increase in sub-Saharan Africa while those related to HIV/AIDS and malaria are decreasing.

The brutal realities of this crisis are laid out in a landmark report released in August 2024 by the Africa CDC, a public health agency of the African Union (AU). The AU consulted a range of experts in public health, microbiology, and veterinary medicine to offer an African analysis of this threat.

The report comes at a strategic time: next week, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) will hold its second high-level meeting on AMR, with the aim of galvanizing urgent action against this threat. Health experts from The Lancet advocate for ambitious targets to be achieved by 2030: they urge world leaders to reduce AMR-related mortality by 10%, inappropriate use of antibiotics in humans by 20%, and their use in animals by 30%.

The urgency of the situation is undeniable, as the report predicts that the situation in Africa could worsen dramatically. By 2050, Africa’s population could double and AMR-related deaths could quadruple, reaching up to 4.1 million per year.

In addition, macroeconomic trends on the continent, such as climate change, urbanization (growing at 3.5% per year by 2050), the largely agricultural economy (17% of sub-Saharan Africa’s GDP, with a 13% increase in agricultural productivity over five years), as well as the spread of zoonotic diseases (up 63% over ten years) will contribute to the worsening of AMR.

The report highlights the gravity of the situation in Africa, where the burden of AMR is particularly high due to the overuse of antibiotics in healthcare and agriculture, inadequate infection prevention measures, and a lack of robust surveillance systems. The AU report reveals alarming data on resistance patterns and highlights the disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations, including children and the elderly.

The fight against AMR requires funding, which currently falls far short of what is needed. It is estimated that an effective response to AMR in Africa would require between $2 billion and $6 billion per year. Yet current funding is ten times lower than that for other major disease fights.

The estimated annual budget for national action plans to combat AMR is only $100 million, or between 1 and 5% of the needs.

Investments in this area would have significant positive impacts. For example, efforts in water, sanitation, hygiene and infection prevention could significantly reduce infections and deaths from diseases, while potentially preventing up to 20% of AMR-related deaths each year in Africa.

A key point of the 2024 report is the call for a unified response by African nations. It calls for strengthening national action plans, aligning them with the AU continental strategy against AMR. This includes improving laboratory capacity, better data collection and sharing, and promoting stewardship programmes to ensure the rational use of antimicrobials. The report also stresses the importance of public education campaigns to raise awareness about AMR and its consequences.

In addition, the report highlights examples of African countries, such as Malawi and Kenya, that have already made significant progress in combating AMR. These successes show that the continent can build on existing models and provide valuable lessons for other countries that still need to scale up their efforts. While much remains to be done, these examples show that African countries are not starting from scratch.

The Africa CDC report is a call to collective action and underscores the need for a robust, multifaceted approach to safeguarding the effectiveness of antimicrobials for future generations. “If left unchecked,” the report warns, “AMR will plunge much of Africa into extreme poverty and cause massive annual losses in gross domestic product.”