Every Saturday, one of our journalists answers, along with experts, one of your questions on the economy, finances, markets, etc.

Published at 7:00 a.m.

Many G7 countries are not federations and the central government must also operate schools, hospitals, transport, etc. To compare apples to apples, shouldn’t we include the provincial debt when we talk about the Canadian debt?

Richard Champagne, LaSalle

Everything is relative, Albert Einstein once postulated. An economist who looks at government debt would not say otherwise. This is what works to the advantage of the Canadian government.

This is what former Minister of Finance and Deputy Prime Minister of Canada Chrystia Freeland said, in many more words, a year before her surprise resignation on December 16. She then announced her three “budgetary anchors”: the federal government deficit should not exceed 40.1 billion, the value of the debt in relation to the country’s GDP should decrease from the 2024-2025 financial year and budget deficits should not exceed 1% of national GDP from the financial year 2026-2027.

It has since been discovered that the dollar value of the deficit is growing much faster than expected. But it increases less quickly than the size of GDP, even if we calculate the debt accumulated by the country’s subnational administrations.

This is what the parliamentary budget officer, Yves Giroux, did last summer.

We estimate that the federal government could increase spending or reduce taxes by $49.5 billion, while remaining fiscally sustainable.

Yves Giroux, parliamentary budget director

As for provincial, territorial, local and Indigenous administrations, their budgetary policies are also sustainable in the long term, according to Mr. Giroux.

“They are sufficient to maintain the ratio of net debt to GDP below its 2022 level for the 75-year horizon. »

Seventy-five years! Such a fiscal horizon, for a Minister of Finance in 2024, is the equivalent of a huge blank check.

This brute

Canada’s gross federal debt is $1,282 billion, or $1.28 trillion (a number, one trillion, that we will have to get used to one day, given inflation, among other things). If we add the public debt of the provinces and territories, the total rises to 2.2 trillion, for the 2023-2024 fiscal year. This is approximately double what the federal and provincial public debt was worth in 2007-2008 (1.2 billion).

These numbers are huge. And yet, they are nothing compared to the 35.6 trillion US dollars (51 trillion CAN) that represents the gross federal debt of the United States.

Ah! But the United States economy is much bigger than the Canadian economy, you might say. Which is absolutely true. But when we put things into perspective, it changes everything.

The International Monetary Fund estimates the U.S. national debt at 123% of the size of the U.S. economy, expressed in terms of its gross domestic product (GDP). GDP has many flaws, but it is still today the benchmark indicator of the size of world economies.

This same calculation allows us to establish that in 2024, the Canadian government debt represented 106% of national GDP. This is less than the 118% of GDP that the federal debt was worth in 2020.

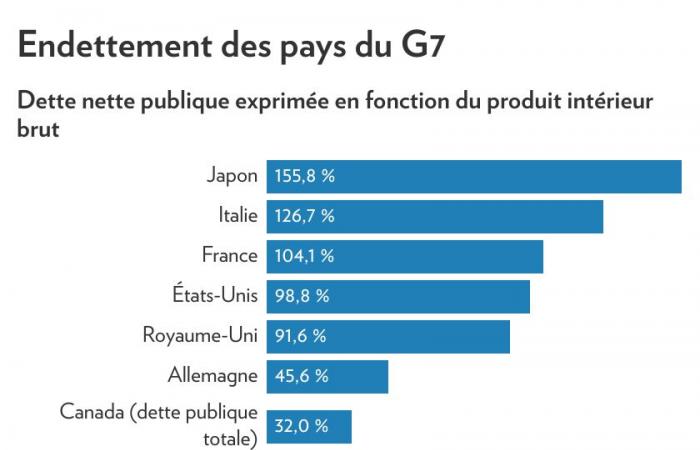

Among the other G7 countries, only the United Kingdom (102%) and Germany (64%) perform better.

And as governments each borrow on the financial markets, it is their own debt which is used to calculate their borrowing capacity and the extent of their repayment, through their debt service.

This net

Canada does better if we contrast its GDP with its net debt, which includes the value of physical and financial assets held by its government. Given that it is the one that has the greatest advantage over the rest of the G7, unsurprisingly, it is this calculation that the Trudeau government favors to justify its high level of spending.

The federal government’s net debt represents 14.4% of GDP. That of Germany stands at 46%. That of Japan, the most indebted of the G7 countries, is 156% of its GDP.

The net debt of all public administrations in Canada is also below that of other G7 countries, at approximately one third of Canadian GDP. The relative value of this combined net debt is expected to decline in the coming years, according to the Parliamentary Budget Officer.

If all goes well. Which is a big “if”. In its own report on the issue, the very conservative Fraser Institute recently expressed concern about excessive debt and its influence on the economy, which would lead public finances into a negative spiral.

Debt service already limits public investment in national productivity, another major weakness of Canada. A more indebted government will invest even less. Then, maybe he will have to raise taxes? Which will scare away investors.

And since in 2024, no one is apparently safe from a surprise 25% tax on the majority of its exports, Canada should not be happy to be doing relatively better than the rest of the G7, because anything can change quickly.

There are limits to everything, including relativity. Einstein would agree on this.