The views expressed in opinion articles are strictly those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the editorial staff.

Published on November 21, 2024

–

A

+

Some urban legends die hard. In the field of economics and politics, the one which describes France as an ultra-liberal hell in which all recent governments without exception, as long as they come from the right, the center and sometimes even the social left- Democrat, have reinforced the characteristics of austerity, breakdown of public services, enrichment of the rich and impoverishment of the poor, undoubtedly holds the rope.

In this speech held by both the far left and the far right for a long time, Emmanuel Macron has become the archetype of the demolisher of our social system. It is true that he sometimes made comments that could easily lead to confusion. We will remember, for example, the “crazy money” episode or his campaign promise to reduce the civil service workforce by 120,000 positions in 5 years. Not to mention that he actually reduced personalized housing assistance (APL) by €5 per month, that he put an end to SNCF recruitment for railway worker status and that he limited the ISF to real estate wealth .

But his predecessor François Hollande, although a staunch socialist, also had to endure the same kind of criticism when he tried to reform the labor code. As for our new Prime Minister Michel Barnier, he certainly took great care to use all the right elements of language on the « justice fiscale » not to offend anyone, but he was nonetheless described as an ultra-liberal subservient to the budgetary rigor of Brussels upon his arrival at Matignon two months ago.

Needless to say, despite appearances, the first two months of the Barnier government have neither succeeded nor even seriously attempted to modify anything truly significant in the frenzied spending and regulatory cavalcade of our social model. Let's give the third time to prove itself, but let's say for the moment that its Finance Bill for 2025, composed overwhelmingly of tax increases and incidentally cuts in public spending, fits very harmoniously into the ” always more taxes, always more resources, whatever the cost” which has been the charm of the French exception since 1974.

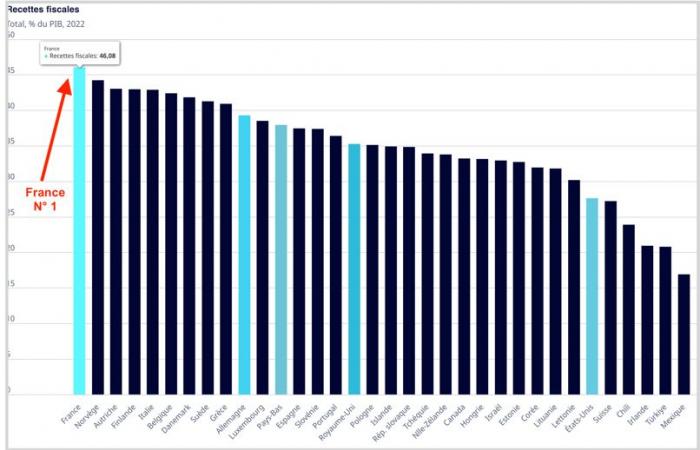

Because ultimately, how is the so-called ultraliberalism made in France characterized? By the fact, unique in the world, that the country is the world champion in public spending and compulsory contributions (taxes and social contributions), as the OECD graphs clearly show:

Public spending, OECD, 2021

Compulsory levies, OECD, 2022

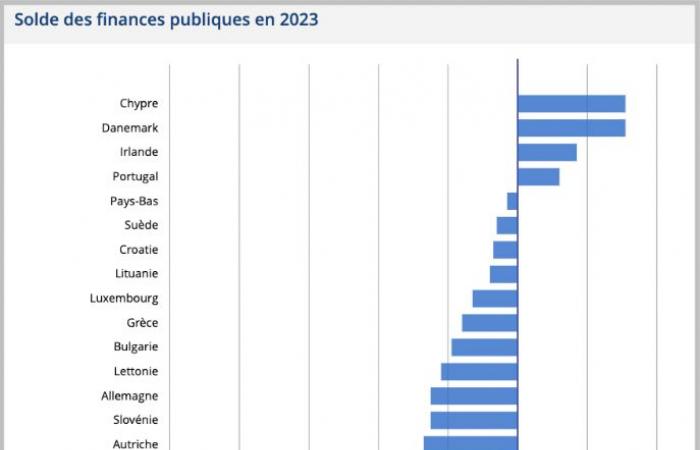

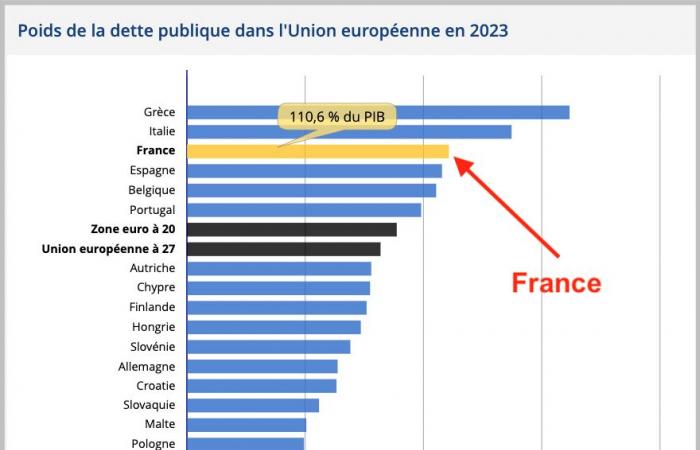

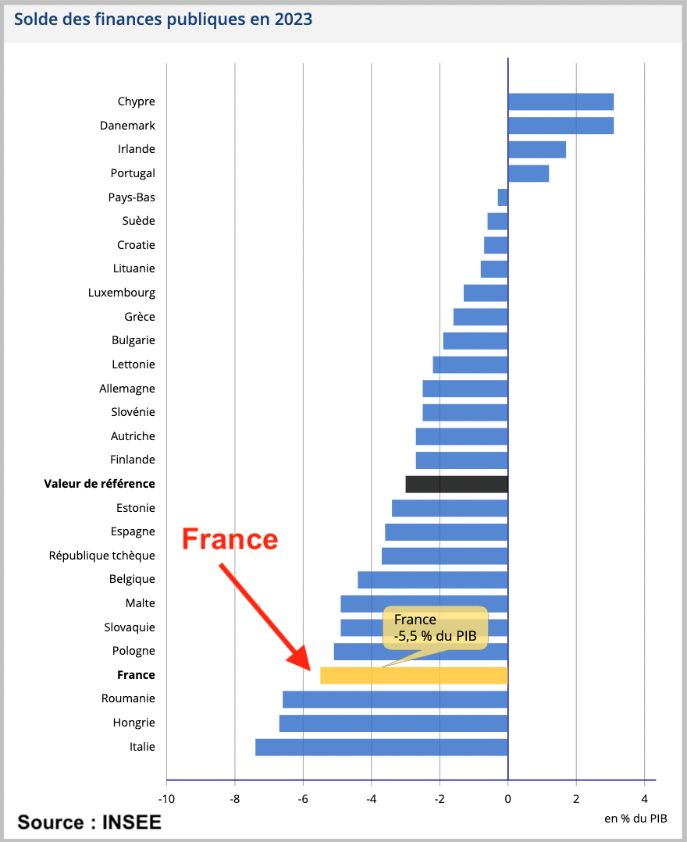

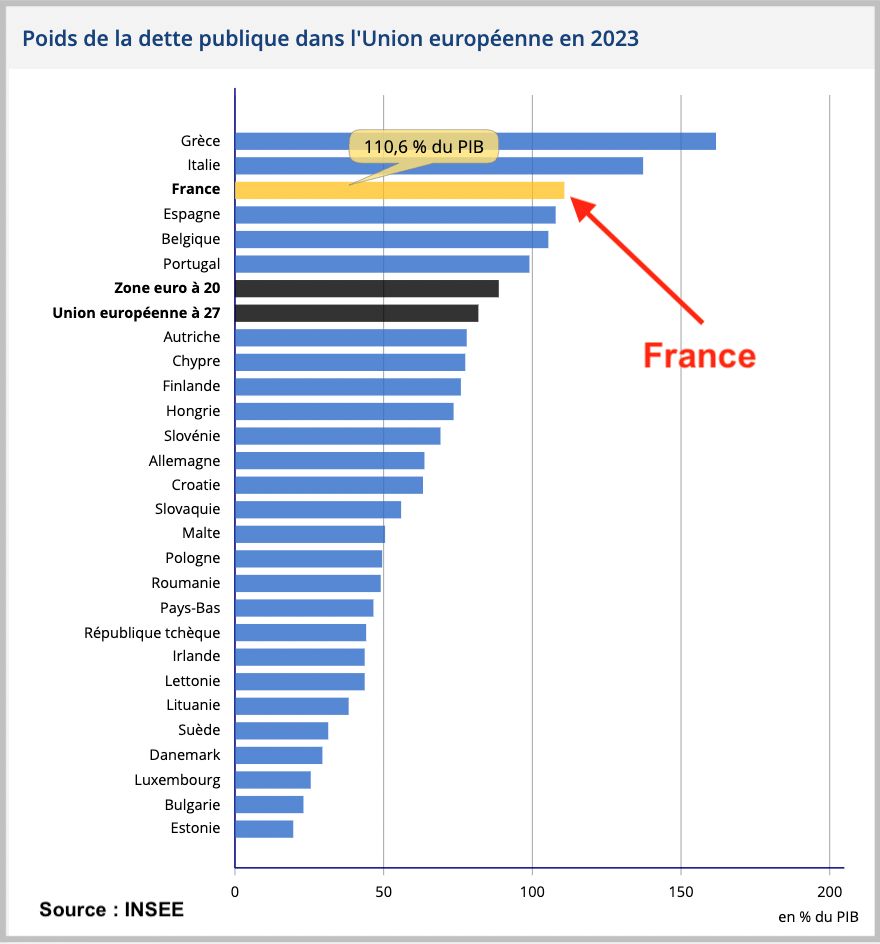

Despite their importance, compulsory levies are far from covering expenditure, which generates a public deficit which is expected to reach 6.2% of GDP in 2024, which deficit in turn generates a public debt forecast at 113% of GDP by the end of the year and 115% for 2025, according to data from the PLF 2025. Here again, France is close to the peaks, both within the OECD countries and in the European Union (2023 figures):

Public deficit, EU, 2023

Public deficit, EU, 2023

Public debt, EU, 2023

Public debt, EU, 2023

But in vain you say and repeat all this a hundred times, you will show in vain, with incontestable figures and reports from the Court of Auditors to support it, that despite the constant increase in expenses, the hospital, agriculture, pensions and National Education have been in deep and perpetual crisis for years, you can expect to be told almost obsessively that what is wrong in this country is its unbridled ultra-liberalism, otherwise said his mind mercantile which only knows profit for the bosses and oppression for others.

Also, to the previous elements that my readers already know inside out, I would like to add a new argument, little developed here until now, but which seems particularly powerful to me.

In September 2023, INSEE published an interesting study on the distribution of income in France and the effects of redistribution. We know that the latter forms the heart of our very strongly collectivized and state-controlled social system, in accordance with the Marxist convictions of its founders Ambroise Croizat or Maurice Thorez, references of the left, who acted at the time (1945) with the blessing of General de Gaulle, reference of the right. Hence a great national unanimity on the subject.

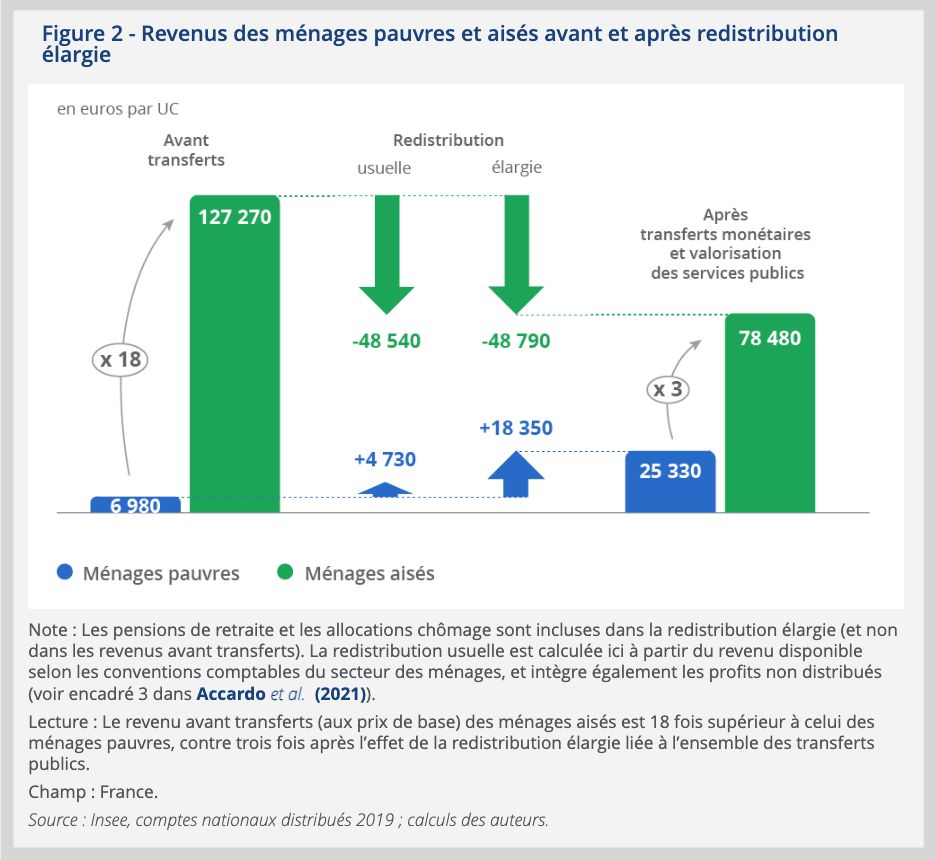

In addition to the monetary transfers corresponding to social benefits and retirement pensions usually used in such analyses, the authors of the study in question integrated a broader redistribution taking into account the valorization of public services – individual services such as health and education, and collective services such as defense or research.

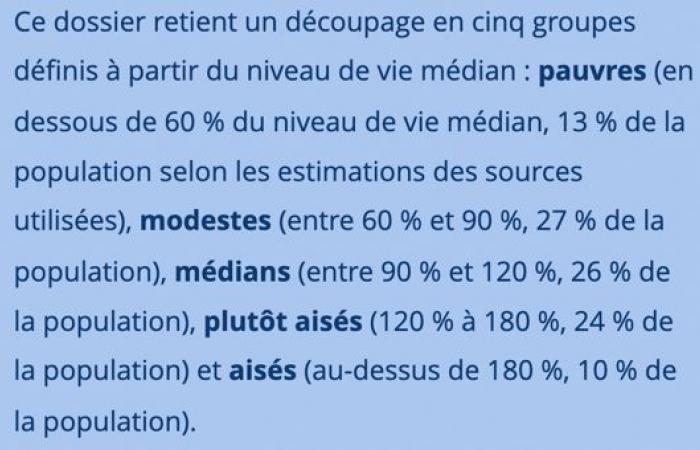

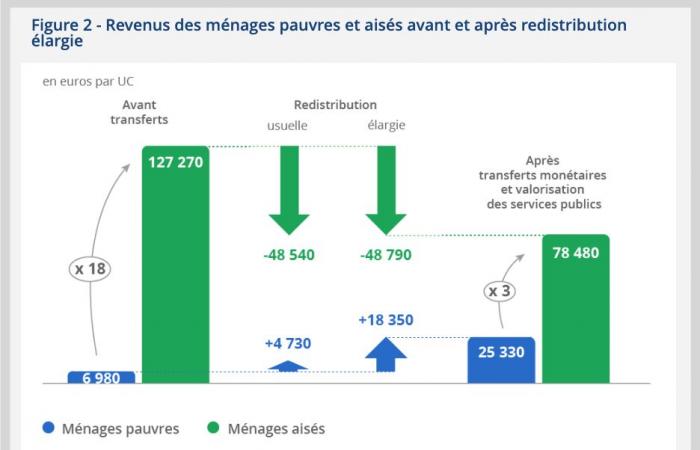

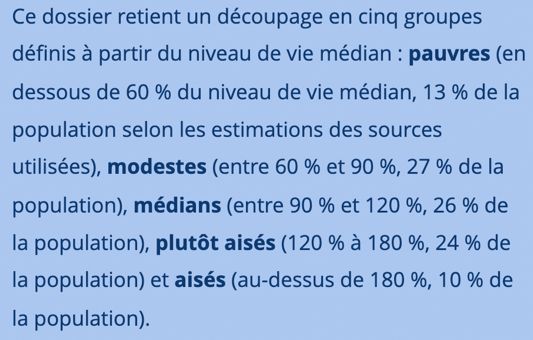

The population is divided according to five categories of standard of living, as shown opposite, and we focus on the two categories located at the high and low ends of the distribution, labeled “poor” and “well-off”.

The conclusion is striking.

The income gap between the poorest 13% and the richest 10% is 1 to 18 before expanded transfers and he retracts to a report of 1 to 3 after expanded transfersas shown very clearly in the diagram below, taken from the study:

In these conditions, it is difficult to claim for much longer that France is rotten by its ultraliberalism without coming across as an individual in very bad faith. The reality is that France is indeed this paradise of egalitarianism and leveling down that we see expressed in a particularly glaring and unanimously applauded way in the Bac pass rate which reached 91.4 % in 2024, or almost 80% of the generation concerned.

In these conditions, it is difficult to claim for much longer that France is rotten by its ultraliberalism without coming across as an individual in very bad faith. The reality is that France is indeed this paradise of egalitarianism and leveling down that we see expressed in a particularly glaring and unanimously applauded way in the Bac pass rate which reached 91.4 % in 2024, or almost 80% of the generation concerned.

Except that all is not rosy in paradise, far from it.

Just as obtaining a Baccalaureate diploma is not, and is no longer, the glorious and systematic guarantee of good higher education and then access to employment without difficulty, the vast redistribution of income is no longer not the united and systematic guarantee that the French live in gentle prosperity allowing the least advantaged people to gradually and joyfully access the middle class.

Quite the opposite, in this fall of 2024 which crowns nearly 80 years of social and solidarity redistribution and 50 years of gaping and voluntary deficits, youth unemployment is (again) dangerously increasing, social plans are piling up (again) , hospitals are (still) navigating between strikes and sporadic walkouts, farmers are (still) in the streets, the civil service is also getting involved and SNCF staff intend to give us the benefit this year (again) of their very personal way of considering freedom of travel ahead of the end-of-year celebrations. As for pensions, we will have to come back to it (again).

Oh, of course, the reasons given by some to support their “righteous anger” all relate to this error of appreciation of economic and social reality that I talk about in this article. It would be the fault of liberalism – and its components competition, free trade, privatization, financialization, etc. Liberalism which, as we have seen, does not exist in France, or very little.

But there is indeed discomfort.

Because redistribution produces nothing. It provides temporary relief, it provides occasionally necessary help, but it does not lift anyone out of poverty. It must be renewed every month, every year, by taking again and again from the income (and assets) of the most inventive, the most productive categories of the population. After a while, the capital necessary for inventiveness and production begins to run out. The fiscal pressure becomes untenable and the State must go into debt to maintain the illusion that everything is going well, while inventiveness and production diminish, bringing with them anemia of growth and employment. And so on.

Precisely the choke point where France finds itself today. And perhaps the right time to say that our economic and social system suffers from structural failures much more than cyclical ones. Rather than doing the same thing over and over again, namely spending more, getting into more debt, taxing more and starting again, with invariably disappointing results, why not start talking without getting angry about what liberalism could do for our prosperity and our freedom?