1/7

“Peplo films”, a theme more than a genre

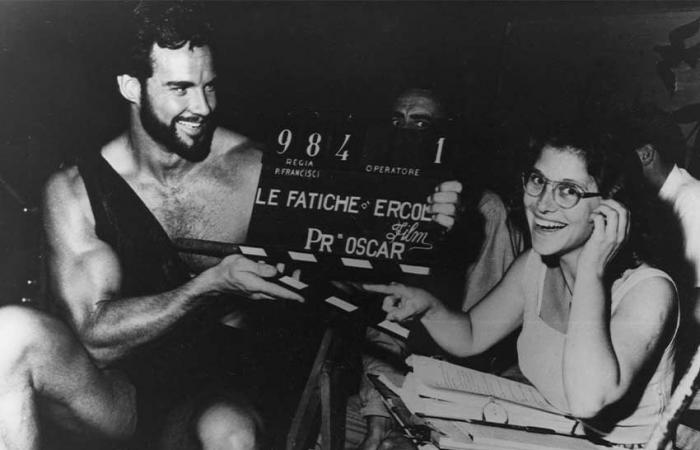

The Labors of Hercules (Pietro Francisci). Coll. Laurent Aknin © 1959 – Oscar Film – Galatea Film

The term “peplum” is a French invention, the result of conversations between three young film buffs in the 1960s. While they were discussing these spectacular costume films in their film club as they approached the end of their golden age, Yves Martin, Bernard Martinand and Bertrand Tavernier designated them for the first time as “peplo films”, named after this tunic worn by women in ancient Greece. From the saucy to the biblical, from the historical film to the Monthy Python-style parody, the peplum is a theme more than a genre, on which folklore such as the demi-god, the gladiator or even the courtesan.

2/7

Great family entertainment

Antiquity and cinema, Ben-Hur chariot, Museum of Cinema and Miniature collection, photo François Ayme © Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé Foundation

From the end of the Second World War to the mid-1960s, it was the golden age of the peplum. We go to the cinema as a family to enjoy a great spectacle served by the development of new processes giving an unprecedented scale to the projected image, technicolor and cinemascope in mind. These films were then huge undertakings, the blockbusters of the time, sometimes the obligatory passage for future big names in cinema, like Leone or Kubrick. Directors, producers and actors, the entire cinema world then moved to the Cinecittà in Rome, this “Hollywood-sur-Tiber” in which an abundance of peplums would be filmed over the course of fifteen years.

3/7

McCarthy among the Romans

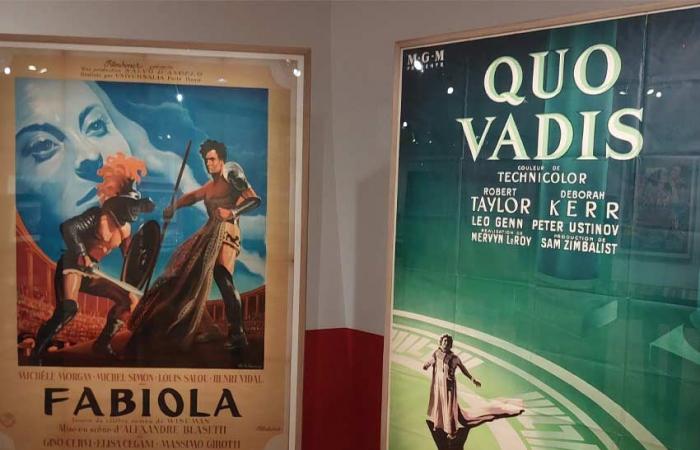

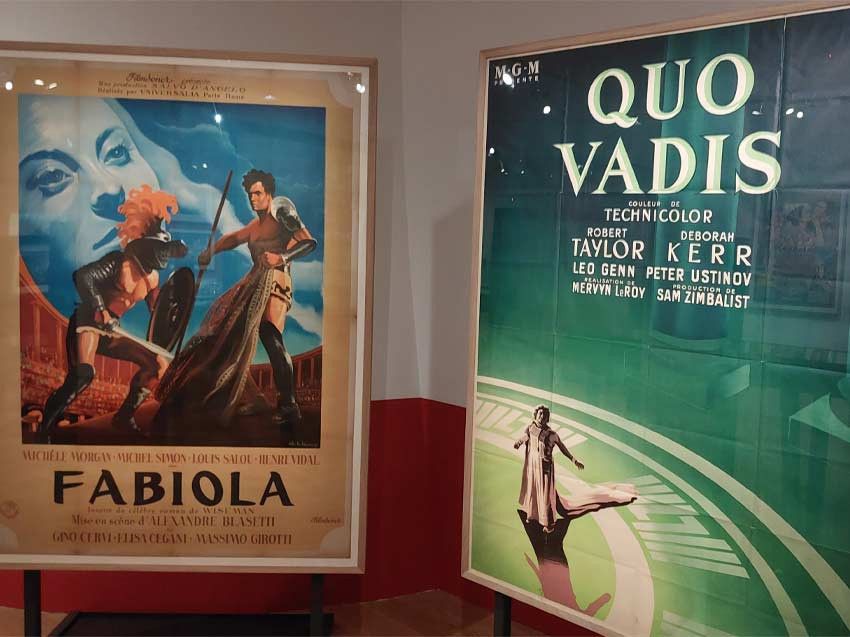

On the left. : Fabiola, Alessandro Blasetti, 1949, poster by Bernard Lancy, Ciné-Images Collection, right. : Quo Vadis, Mervyn LeRoy, 1951, Olivier Romulus collection © Connaissance des Arts / Alexandre Hannebicq

Like all Art, representations of Antiquity in cinema do not escape an underlying political text. If Carmine Gallone’s Scipio the African in 1937 is an archetype of the propaganda film, Mussolini fascist in this case, the post-war peplum is marked by the dialectic of the Cold War. A tyrannical Roman emperor, the embodiment of the “red threat”, oppresses his people or a social group, often Christians, who aspire to live free and build democracy. The Quo Vadis of 1951, directed by Mervyn LeRoy, is a textbook case, with little regard for the historical veracity of the facts depicted.

4/7

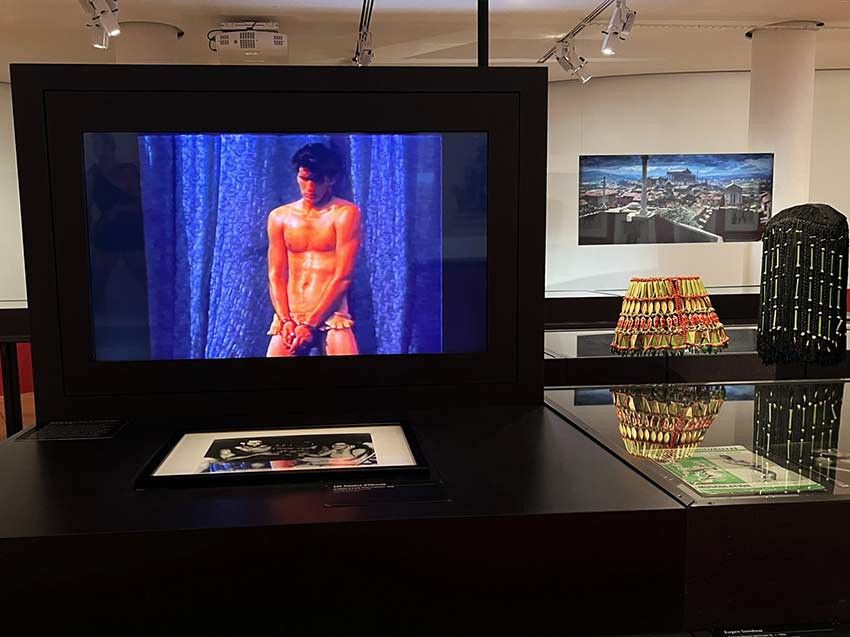

The Art of Transgression

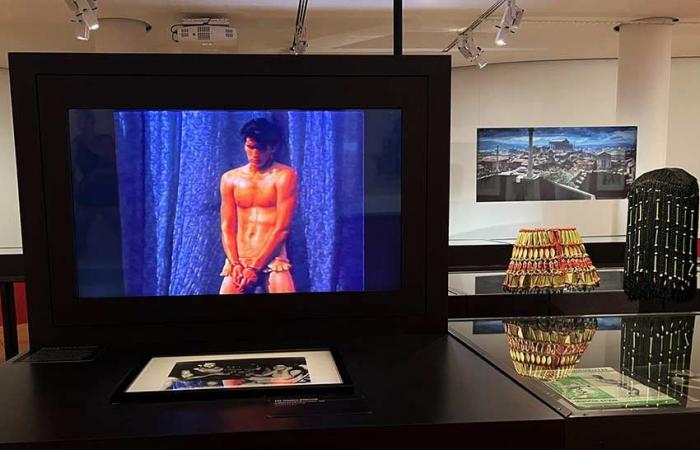

Antiquity and cinema, film from the Bob Mizer Foundation collection, wigs coll. Greg Schreiner, photo Fondation Pathé © Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé

The period of the golden age of the peplum also corresponds to the years of implementation of the Hays Code, which established censorship in the United States. Filmmakers compete in inventiveness to try to circumvent it, sometimes in an unsuccessful manner: in a scene from Kubrick’s Spartacus, Crassus, the Roman patrician master of young Antoninus, speaks to him of his taste for “snails and oysters”, implying his bisexuality. The scene will be cut from the original cut, before being put back years later with a redub of Crassus’ voice by Anthony Hopkins!

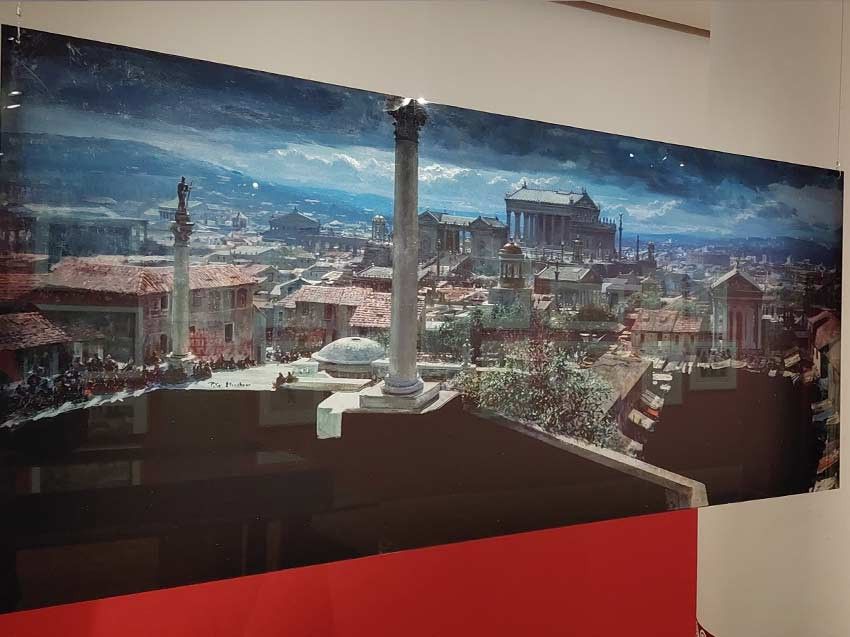

Spartacus, Stanley Kubrick, 1960, Peter Ellenshaw, matte-painting, 1/1 reproduction on plexiglass from the original on glass, kept at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures © Connaissance des Arts / Alexandre Hannebicq

Widely used in fantasy and science fiction productions since the 1930s, matte painting is a glass painting process used to represent complex decorative elements on screen at lower cost. Peplums also use it extensively, for example to represent the background of a large city or landscape. The desired element is painted on a glass plate placed on the camera, empty spaces allowing the filmed scenes to be inserted.

6/7

Grandeur, decadence and renewal

Antiquity and cinema, dress by Mimi Coutelier, Quarter to two hours BC, Coll. French Cinematheque, photo F. Ayme © Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé

The 1960s saw the gradual loss of steam of the genre, faced with an overflow which led to public weariness. Antiquity abruptly disappears from cinema screens after more than a decade of reign over major productions, sometimes returning to the stage in front of the camera of authors like Fellini or Pasolini, or in parodic comedies with Coluche in Two Hours Minus quarter BC by Jean Yanne (1982), Monty Python in Life of Brian (1979) or even the first adaptations of Asterix on the big screen from the 1990s. wait until 2000 and Ridley Scott’s Gladiator to witness the return of the great American blockbusters once again exploring the immensity of the peplum genre.

7/7

Antiquity and Cinema

The Queen of Caesars by J. Gordon Edwards, 1917, Private collection © Fox Film Corporation

“Antiquity and Cinema”, Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé Foundation, 73 avenue des Gobelins 75013 Paris, from December 12, 2024 to March 29, 2025