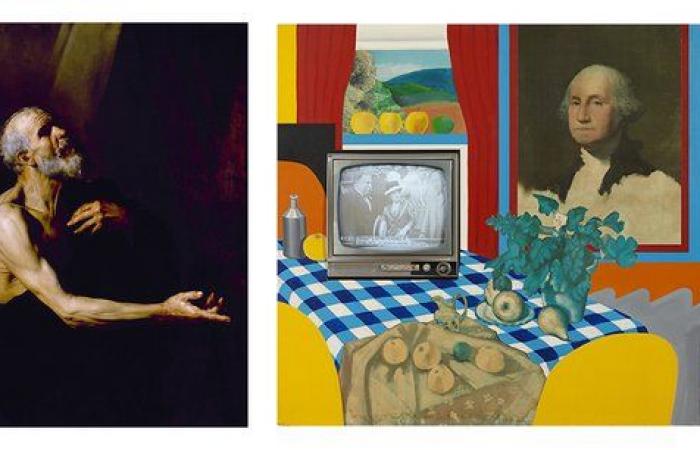

Understanding, affection, compassion, help, love… This is what the paintings of Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652) demand. His works are hands extended to visitors, literally and figuratively. The characters painted by Ribera, super saints, mythical heroes, poverty-stricken men and women of the street, all invite us to witness their distress, their solitude, their suffering. Ribera tells us about them. This is why the exhibition is exciting.

Who has never suffered from feeling different, from sliding towards old age and death? Who has not suffered disappointments in love, the absence of answers to existential questions? Who has not sacrificed a minute, a day or their entire life for someone or for a cause? Who has never been trampled, eliminated, for a moment or an entire existence? Ribera is the lucid painter of a human condition that is not always pleasant.

Art history: the temptation of Tangier

Ribera’s work scratches but does not hurt because the paintings are aesthetically refined (no landscapes to distract the eye), powerful, simply beautiful. The expressions of the painted faces are strong because they are real. Ribera’s characters appeal to us because they often face the viewer. They take us to task. The paintings are harsh, sometimes cruel but never contemptuous or condescending. Ribera loves his neighbor. He knows him. Miserable then powerful, he was both. He paints what he experienced and saw.

He was born on January 12, 1591 in Xàtiva, near Valencia, Spain. At 15, he left the kingdom for Italy. He lived in Rome for ten years before ending up in Spain again, almost. When he arrived in Naples, one of the three most powerful cities in Europe, the vibrant city was under Spanish domination. The shoemaker’s son quickly joins the big leagues. He marries the daughter of a famous painter. She opens many doors for him. Viceroys and eminent members of the clergy order from him and sometimes choke!

His painting is raw, even violent

Because be careful, Ribera is a revolutionary. He does not paint men and women with classic, idealized beauty. He finds his models in the street, representing them as they are. He respects them while transforming them into saints or martyrs, which is what those who finance him want to see. Saints or martyrs therefore, Ribera offers them the faces of thugs, of marginalized people, of poor people with defeated faces and bodies. His painting is raw, even violent, all in chiaroscuro.

Doesn’t that remind you of anything? Just before Ribera, another painter shook up the painting world: Caravaggio. Master of the movement called tenebrism, he is twenty years older than Ribera, both fortunate and unlucky. Fortunately, Caravaggio opened the way to raw painting. Ribera of course saw Caravaggio’s paintings. They may have crossed paths in Rome in 1605. Ribera, influenced by Caravaggio, became his stylistic heir, so much for luck. His bad luck? Caravaggio entered History, eclipsing his successor.

The exhibition attempts to right this injustice. In his time, Ribera was a respected and well-known master, but time has faded him. In addition to the genius and pictorial courage of Caravaggio, History has perhaps also remembered the latter for a reason external to painting, his very life, dissolute and sulfurous. Pasolini before Pasolini, Caravaggio was assassinated for his way of living and not his way of painting.

Ribera died, “happily”, at the age of 61, in 1652. Too bad for his legend, but his style remains. Ribera’s moving hands emerge from pleated fabrics, purple, blue or blood red. Like the stage curtains, they dramatize, dramatize what the visitor sees, beings with pale flesh. Would Ribera have seen paintings by another Spanish painter, El Greco, who came to Venice before him?

Note Ribera’s smiles, rarely represented in painting due to dilapidated teeth. Ribera dares. A club-footed beggar, a young girl with a tambourine, Bacchus himself, the painter offers a collection of toothless people whose dental reality in no way diminishes their dignity. Ribera respects humans, loves them. The Petit Palais is a feast as the paintings on display are captivating masterpieces. The exhibition, organized by the discreet and reckless director of the museum, Annick Lemoine, is the big slap of the moment.

EXHIBITIONS: AFP celebrates 80 years of liberation in photos

Works full of humor

From pain to the refrigerator, from the darkness of the soul to the toilet bowl, in six stations, line no. 1 takes you from the 17th to the 20th century, from darkness to joy, from the depths of the human condition to the superficiality of the condition of consumer, going from the Petit Palais to the Louis Vuitton Foundation. The exhibition “ Pop Forever » embodied by the inventive Tom Wesselmann (1931-2004) brings lots of color to the eyes. Wesselmann recovers and makes fun of American consumer society, in the midst of a crisis of euphoria in the 1950s and 1960s.

Material occupies minds as it clutters daily life. An excellent designer and painter, Wesselmann takes the codes of advertising and twists them. He recovers everything, transforms, accumulates, associates, juxtaposes. A fake bathroom with a real towel rack, an apartment interior with a real window overlooking a fake landscape, a real radiator next to a languid and naked painted woman, a real television set in a fake living room at the time when it enters every home.

Light, Wesselmann? No way. He is a worried and serious man, passionate about psychoanalysis who relieves himself of his torments by imagining unbridled, joyful works, full of humor and fantasy. Like Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, also visible in the exhibition, Wesselmann is a trendy code breaker harvester-beater-mixer-messer. It should be taken seriously as pop art is when it is often reduced to decoration.

The movement reflects a crazy era of assumed excesses. Pop art often uses humor and derision. There are few exhibitions where you can hear bursts of laughter! Things are laughing at Vuitton. For dark, Ribera, for color, Wesselmann, both highly recommended.

Little Palace “ Ribera – Darkness and light »until February 23, 2025 Paris Musées Edition, 49 euros

Louis Vuitton Foundation Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &… »until February 24, 2025 FLVGallimard edition, 45 euros