At the cinema, The Nevenka Affair looks back on the fight of this woman, the first to denounce an elected official for sexual assault in Spain.

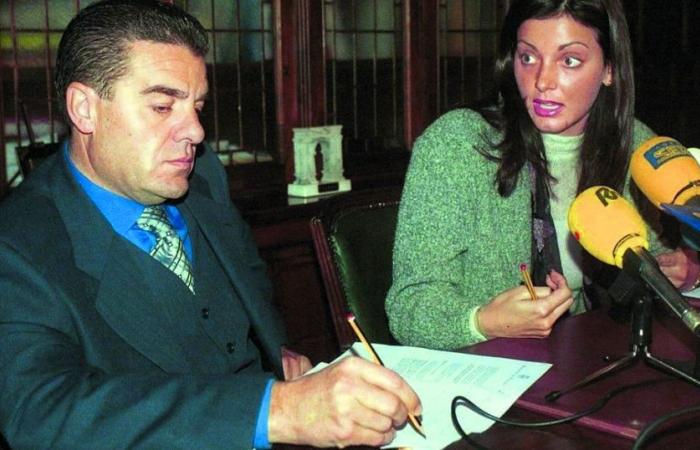

It was twenty-three years ago, on March 26, 2001, the Spaniard Nevenka Fernández, finance councilor in Ponferrada, called a press conference in this medium-sized town in the northwest of the country. She publicly accused the mayor, Ismael Álvarez, of sexual harassment and took the matter to court. A year later, she became the first Spaniard to have a politician convicted for such acts, but the affair was not without consequences for her: having become an outcast, she was forced to leave her native land.

Having had a wide impact in Spain, this affair was at the center of Nevenka Fernández breaks the silenceNetflix documentary series released in 2021. “Thanks to MeToo, after hearing the testimonies of so many women or even men abused by members of the clergy, I understood that I was not alone and that it was important that I share my story. This documentary was my catharsis: I had to make peace with myself and the people I loved,” says Nevenka. She thinks about closing the page for good, but the director Icíar Bollaín suggests that she adapt her fictional story for the cinema.

”

data-script=”https://static.lefigaro.fr/widget-video/short-ttl/video/index.js”

>

Known for her commitment, the Madrilenian has already achieved Don't say anythinga film about domestic violence. Nevenka agrees. “The emotional power of cinema makes it possible to show the mechanisms of control and its psychological consequences differently,” she explains. I am not telling my story to take revenge, but to help women who are going through similar situations and to question the way society responds to these injustices.

At the cinema on November 6, The Nevenka Affair returns to the ordeal experienced by the young woman, the process of annihilation of her personality implemented by her attacker, the denial of society and her fight. Because, at the time, when she spoke, no one believed her. For society at the time, she did not have the profile of the “good victim” and the mayor was the king of the city.

Harassment and assault

When she joined the municipal council of populist Ismael Álvarez in 1999, this trained economist was 26 years old and considered politics to be a virtuous commitment. The reputation of don juan of the mayor of Ponferrada precedes him, but she refuses to listen to the gossip and wants to believe in the honesty of this charismatic man, who, shortly after she enters his service, loses his wife to 'a cancer.

Ballesteros / MaxPPP

They begin a relationship, very brief, but when she decides to end it, he can't stand it. Telephone persecution, humiliation in public, stratagems to force her to be alone with him: harassment takes place, up to sexual assault.

“At the beginning of her story, Nevenka probably did not realize herself that she was a victim,” explains director Icíar Bollaín. Because they had an affair, because she had cultural and intellectual baggage, because we think that it can't happen to us…” Nevenka nods. “I come from a conservative family, and I come from a patriarchal country that does not accept women stepping out of line. I had to forget what society had taught me to understand what was happening to me. »

The smear campaign

At first she believes that she can get through it alone, that perhaps he will find love and free her. She does not want to resign, “leave with her head bowed like a guilty person”, risk causing the ruin of her parents who receive subsidies from the town hall. But his life is hell. “To harass is to destroy the identity of the other. I no longer breathed, I no longer ate, I no longer slept, I no longer recognized myself. I wanted to die sometimes.” In September 2000, she took sick leave and went to Madrid to find Lucas, her boyfriend.

Ana F. Barredo / MaxPPP

The mayor leaves her yet another insulting message: she hears it, and so does her friend. An anxiety attack sends him to the psychiatric emergency room. Supported, she begins to integrate: “Going to court was my only option to not die, to regain my dignity. » When she denounces the mayor, the media portrays her as an ambitious, lying, careerist young woman.

A smear campaign said she was alternately a drug addict and a member of a sect. “Álvarez is all-powerful, and the word abuse is barely spoken,” says the director. And then, twenty years ago, the notion of consent was far from being at the heart of the debates, especially in a patriarchal country like Spain.”

A dearly paid victory

Nevenka stays in Madrid during her studies, she works in the factory, her parents are ruined and forced to sell everything. At the trial, her colleagues sided with the stronger side: they said she was incompetent, jealous, a dilettante. The attorney general attacks her ardently, as if she were in the dock – he will be replaced during the trial – but Nevenka's testimony changes the situation: Ismael Álvarez is sentenced to a fine of 6,840 euros and 12,000 euros in damages. He resigns, but it is she who pays the high price. No one wants to hire her anymore, so she leaves Spain to start a new life. “Despite the injustice, I prefer to see the glass half full: leaving allowed me to start again, to think of other possibilities. Today, I live on my terms.”

FEDERICO VELEZ / MaxPPP

At 50, Nevenka has started a new life in Dublin with Lucas and his children, and works for Airbus. Before retiring, his attacker remained a businessman, created his own party and won seats in the 2011 elections. “Many people still believe he is innocent,” says Nevenka. “I not only fought against him, but against a social and cultural construction.” In her country, however, the Spaniard has opened the way to the debate on the violence exercised in circles of power. More than twenty years later, speech has become freer, and listening has changed.

“There is still resistance if we are to believe the Mazan rape case or that of the businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed: he had to die for us to learn that he had attacked dozens of young girls with the support of his entourage, concludes Icíar Bollaín. But it is undeniable that those who speak are better heard, in particular because society better understands the mechanisms of harassment and control. Nevenka wouldn't be so alone today. However, I hope that there comes a day when it will no longer be necessary to make films about stories similar to his.”