She had disappeared a little from people’s minds. Vladimir Putin, Kim Jong-un and a few others have made it fashionable again: the nuclear threat. It occupies the rooms of the Museum of Modern Art in Paris until February 9, 2025 for a current exhibition. “The Atomic Age” deals with the subject from the point of view of plastic creation. In addition to the works, there are documentary sections where texts and images accumulate, often redundant. There are so many of them and hung so tightly that it sometimes becomes difficult to know which element corresponds to which cartel and the eye no longer knows where to land. The same goes for the paintings, which follow one another along the walls at a more than sustained pace. All this is a long journey, and it is prudent to set aside two hours of your time to try to see and read everything.

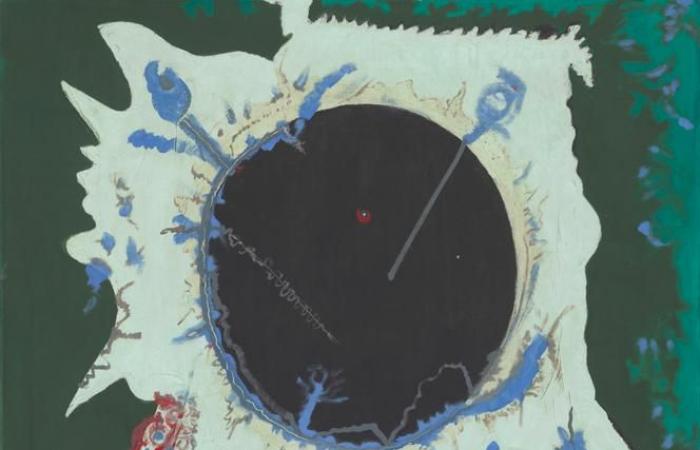

There are, in this abundance, capital works, starting with the one that welcomes visitors at the entrance, Pagan Voidby Barnett Newman (1905-1970), a black circle in the center of a white cloud which appears liquid and where blue splashes float. Newman being American and the work of 1946, its presence in this place suggests recognizing a reference to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki the previous year.

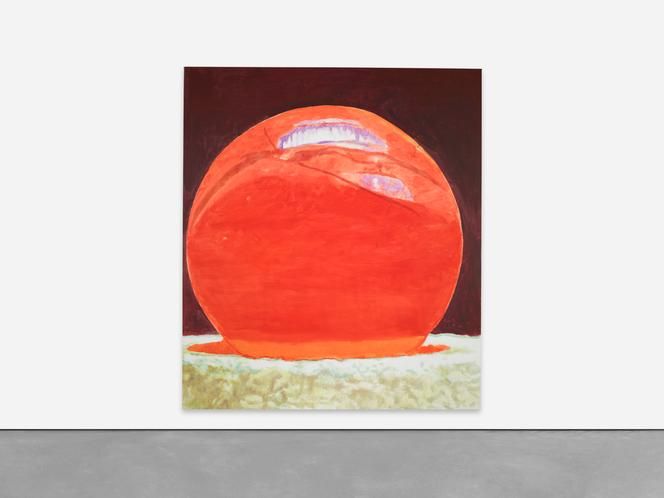

This interpretation is not the only one that can be proposed and we have sometimes believed to see in it the representation of an eclipse, but, whatever the one we choose, there are few works which, by the means of color and shapes give off a denser feeling of fear. At the other end of the exhibition is Eternityby Luc Tuymans, a large red sphere irradiating its light which we do not know if it is the cloud of an explosion or the dome imagined by the Nazi physicist Werner Heisenberg, one of the actors of the Uranium project decided by Hitler in 1939. Here again, it is to the form and chromaticism that the work owes its strength, more than to what it would show. The two works thus respond to each other at a distance.

Erasure of humanity

There are others that are just as remarkable and which raise no fewer questions. Do they undoubtedly relate to the atomic subject? For some, it is certain, as the artist put so much emphasis on it. For his canvas Uranium and Atomica Melancholica Idyll from 1945, Salvador Dali accumulates symbols. Neither the bomber, nor the bombs, nor the pale specters on a black background are missing. No ambiguity and no excitement: a laborious exercise in style. There Nuclear composition (1952), by Gianni Dova, is infinitely more expressive, although Dova is less known than Dali and his almost abstract and non-narrative canvas. Even so, its title is self-explanatory. This is not the case of Eagle’s Law (1951), d’Asger Jorn, de The Unthinkable (1958), by Roberto Matta, or by Space Light (1960), by Francesco Lo Savio, but we do not doubt for a moment that they are in the subject, each in their own way, and that their authors project in painting the anguish of the erasure of humanity.

You have 58.71% of this article left to read. The rest is reserved for subscribers.