The Federal Reserve will face a weakening job market, an intransigent president and persistent inflationary pressures.

Next year, the Fed may find itself in a bind. On the one hand, the two “hammers” of the weakening of the labor market and the incessant pressure that President Trump may exert could push President Powell to accelerate the rate cuts. On the other hand, the “anvil” of persistent inflationary pressures could considerably limit the Fed’s room for maneuver in terms of easing its policy. The clash between these opposing dynamics could well call into question investors’ consensus optimism for 2025.

Over the past few weeks, strategists from Wall Street banks, institutional asset managers and private banks have released their 2025 outlook reports, which have been generally optimistic about the economy and risky assets. , especially US stocks. This contrasts sharply with their forecasts from twelve months ago, when fears of a recession in the United States dominated, a pessimism that proved unfounded as the economy re-accelerated towards GDP growth of 2.7% and that American stocks recorded returns above 20% for the second year in a row. Will the American economy once again defy consensus expectations? And what could this mean for financial markets?

First hammer – the weakening of the job market

US labor market data for November was mixed. The increase in nonfarm payrolls in the establishment survey rebounded from October’s low due to hurricanes and Boeing, rising from 36,000 new jobs to 227,000. Although the November figure is significantly higher than the average of 201,000 for the previous twelve months, the October-November average of only 131,500 does not suggest a reacceleration in employment growth.

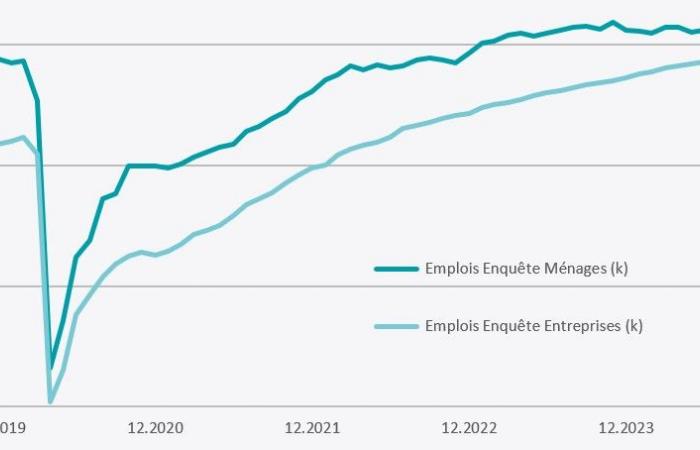

Similar mixed signals were observed in the parallel household survey. Despite this increase in non-farm payrolls, the unemployment rate rose to 4.2% in November. It has been rising steadily since April last year, an increase of 1.7 percentage points. Unlike the establishment survey, households reported a decline of 723,000 employed people in October and November (see chart below for diverging trends between the two surveys). Additionally, the number of inactive people increased to 101.2 million, the highest level ever outside of the pandemic lockdown period. Furthermore, the number of long-term unemployed continues to increase. Today, 1.7 million Americans have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more, a 42% increase from this time last year and the highest level in nearly three years.

These signs of underlying weakness will certainly have strengthened the determination of the Federal Reserve (Fed) to continue its rate reduction cycle this Wednesday.

Second hammer – an uncompromising president

Over the past few decades, the Fed’s independence from political influence has remained largely unchallenged. This independence was first achieved by Fed Chairman Thomas McCabe in 1951, when the central bank limited its purchases of Treasury bonds during the Korean War in order to ease inflationary pressures, despite heavy pressures by President Harry Truman to do the opposite.

The singular exception to this norm occurred during Donald Trump’s first presidency, during which he used his Twitter platform to criticize Fed officials on more than a hundred occasions, according to the Brookings Institute . Most of the criticism came after Mr. Trump nominated Jerome Powell as Fed chairman, believing him to favor low interest rates. However, the latter has maintained rates much higher than those of the US’s trading partners, such as the eurozone, which prompted the president to declare that Powell was a “greater enemy” than Chinese President Xi Jinping.

During his 2024 presidential campaign, President-elect Trump sent clear signals that pressure on the Fed would resume once he returned to the White House. On August 8, for example, he said he believed he should “have a say” in setting monetary policy. He has since been more conciliatory, saying last weekend that he would not seek to oust Mr. Powell before his term expires in May 2026. However, that would not prevent him from again formulating strong criticism in the meantime. Additionally, aspects of Mr. Trump’s policy agenda could make life difficult for Mr. Powell, including his promise to impose colossal tariffs on imports, which could push inflation above 3 .0%, according to Goldman Sachs.

Once again, these factors suggest an easing bias in monetary policy.

The anvil – persistent inflationary pressures

The market reacted well to consumer price inflation (CPI) figures in the United States last week. The probability of a 25 basis point rate cut this Wednesday increased from 86% to 98%, with operators being reassured by the fact that the price increases were in line with expectations and believing that the Fed could continue to ease his policy.

However, November’s headline CPI rose 0.3% month-on-month, the fastest pace since April, while the year-on-year rate reached 2.7%, up from 2.6% in October. These increases took place despite the slowdown in the housing component, which fell from 0.4% to 0.3% month-on-month, as many operators had hoped. Prices of services and goods both rose 0.3% last month, the same pace as in October. However, accelerations were seen elsewhere – for example, food prices increased by 0.4% month-on-month, compared to 0.2% in the previous month. At the level of core inflation (which excludes volatile food and energy prices), prices increased by 0.3% month-on-month and by 3.3% in ‘one year on the next, the same rate as in October.

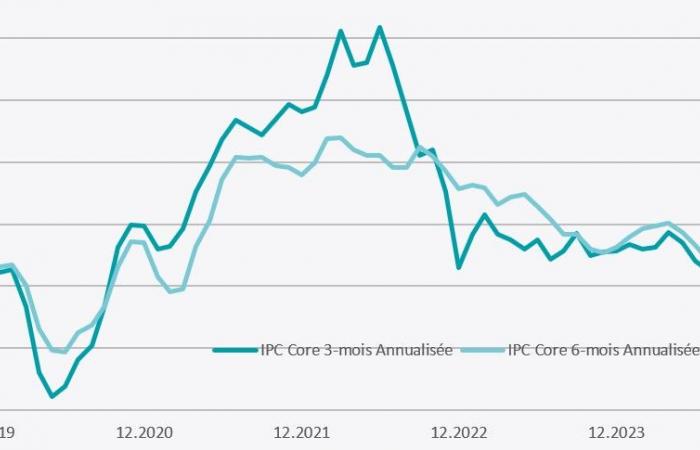

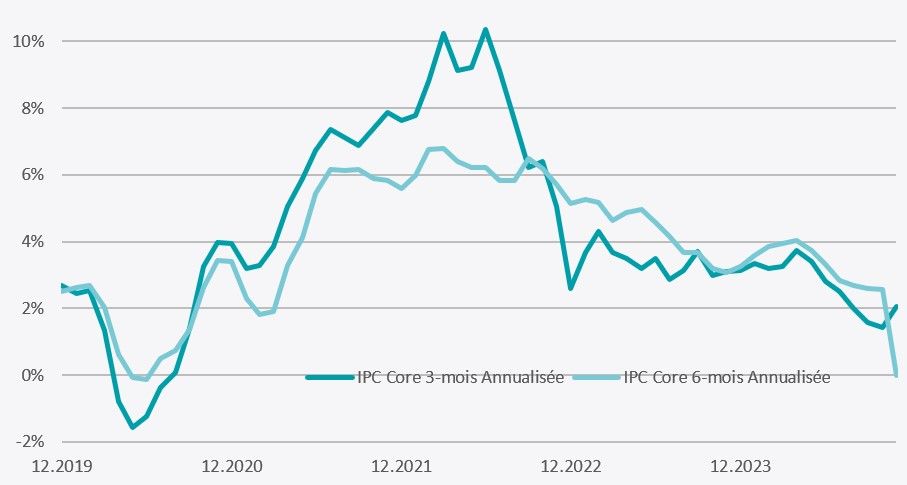

Looking at the annualized trend in inflation over the past few months, the reacceleration becomes clearer. As the chart below shows, underlying CPI appears to be recovering. The six-month annualized rate reached 2.9% in November, up from 2.6% in the previous two months, while the three-month annualized rate rose from 1.6% in July to 3.7% on last month.

This trend is supported by other measures – for example, although the Atlanta Fed index of twelve-month core sticky CPI has slowed, it has still stood at 3.9% in November In addition, producer prices started to rise again Last Thursday, the producer price index (PPI) in November reached 0.4% month-on-month. 3.0% year-on-year, well above expectations of 0.2% and 2.6% as well as October’s 0.3% and 2.6%.

In this context, we are skeptical that the Fed will feel comfortable with the market’s optimistic expectations for rate cuts next year. We wouldn’t be surprised if the tone of policymakers’ statements doesn’t become somewhat hawkish after this week’s rate cut.