By Mohamed Kerrou – This is a book that can be read in one sitting as the limpid and rich writing of the text accompanies, while embellishing it, a very sustained political reflection. That of a remarkable intellectual of the “perspectivist” left whose prison career was accompanied by a criticism of civic engagement. And it is not without reason that Mohamed Salah Fliss dedicates this book of interviews to a distinguished comrade, Gilbert Naccache, to whom he pays homage along with an appropriate analysis of the profile of the left activist (pp. 87-91 ). For Fliss, Gilbert Naccache embodies, with his strong personality, the figure of the committed and irreducible intellectual, hardly bending in the face of the violence of power, while distinguishing himself by a humanist ethic and a deep sense of friendship. The narrator interprets Naccache’s original attitude by his specific militant status (“coming from a different cultural horizon”) and his rejection of “populism”, this diffuse feeling among left-wing activists. It was also the day after Gilbert’s departure that the interview project proposed by the academic Mohamed Chagraoui to the essayist Fliss, who had already published five books worthy of interest: Homeland of Stars, I am here; Uncle Hamda, the porter; Detained in my homeland; Living in my name. Critical essays; Love didn’t lie to me.

Around this abundant literary work, a most fruitful dialogue was established between Fliss and Chagraoui with questions and answers broken down into three parts: the local and global context determining the activist’s trajectory; the intellectual attitude towards the vagaries of political history and, finally, the axiological and political issues of memorial writing. In the presentation of the book, the analyst Chagraoui does not fail to highlight the constants of Fliss’s “unclassifiable work” with his reflections nourished by the breath of freedom. Among the major lines of force, memory stands out as a perspective for constructing the personality and the future of the author and the permanent reference to the individual-subject, producer of meaning and actor of the History. The result is a writing of the memory of emancipation revealing a readability of the political and intellectual life of the Bourguiba years (1956-1987), breaking with the official memory judged by Chagraoui as being “totally sectarian and fundamentally reductive” (p. 15), or even “truncated, falsified, politicized, oriented…” (p.17). We could of course discuss this value judgment which remains to be demonstrated, with supporting texts, as it is true that the official discourse and Bourguibian memory are based on historical documents and rational argumentation, despite their political bias and cult of personality of the “historical and charismatic leader” who was Habib Bourguiba, the founder of the national state. It goes without saying that plural memory is not limited to Bourguiba memory and that it goes beyond the axial narration of Bourguiba – the “Ipsi Conferences” of 1973 – and the historiography established by Mohamed Sayah. In fact, it incorporates the memories of former companions, activists and servants of the State, the most recent of which is the testimony of former minister Driss Guiba, Sur le chemin de Bourguiba (Cérès, 2024).

It remains that the remarks intelligently combined and developed by the analyst Chagraoui and the analysand Fliss deserve greater visibility, commensurate with the legitimacy of the “voice of youth” of the time aiming to change discourse and power. especially since it is “integral part of the dynamics of our society” et “one of the authentic products of an intellectual and civic awakening”. The strength of this alternative discourse lies precisely in its capacity to fill a “empty memory”to avoid “victimism” environment of left-wing activists and to propose, by adopting a critical spirit, “new impulses and new horizons” for political thought and practice.

The richness of the interviews in question, which are clearly evident in the sincerity and clarity of the subject, is to allow a journey through space and time, from the affair of Bizerte – the “martyr” city – to the “Perspectives” movement. -Al ‘Amel Ettounsi”, going through related subjects such as the independence of Tunisia, political conflicts, the flaws of clandestinity, the profile of the left activist, the question of human rights and the penalty of dead, etc. Among the fascinating and controversial subjects within public opinion is obviously “the portrait of Bourguiba” (pp. 83-87) which seems to take on a central place due to the historical role of the “national leader” as well as Fliss’s insight in painting a nuanced picture denoting an evolution of point of view, from the subjective to the objective . Taking into account the complexity of the character and the historical situation of transition in Tunisia, the analysis highlights abuses, crises of legitimacy, errors of choice resulting from personal power and the “shipwreck of old age”. So many elements which jointly ended up generating the coup d’état of November 7, 1987, not to mention the repressive practices towards political opponents. The established assessment is, despite the radical criticism which does not take into account the depth of Bourguibian reforms, rationally argued without giving in to the feeling of hatred and revenge on the part of a free man who is “remained standing” while preserving his dignity in captivity. All of the interviews stand out, in essence, through lucidity, honesty and the hope of a better life to which new generations aspire in symbiosis with the voluntary and selfless sacrifice of their predecessors.

In short, this book presents itself to us as a couch of political psychoanalysis, where the analyst Chagraoui offers the opportunity to the analysand Fliss who does not fail to finely evoke the figure of the father, to “to work” his ideas by carrying out a real «cure» of memory of the past and the present, these two inseparable facets of the current and the contemporary. At a time when the country seems intellectually bloodless, due to the withering away of political and intellectual debate, I cannot recommend enough that you read this book, the inspiration of which is not without evoking this formidable sensation experienced and expressed with tact. by Fliss: “the time to read, like the time to love, expands the time to live.” (Daniel Pennac).

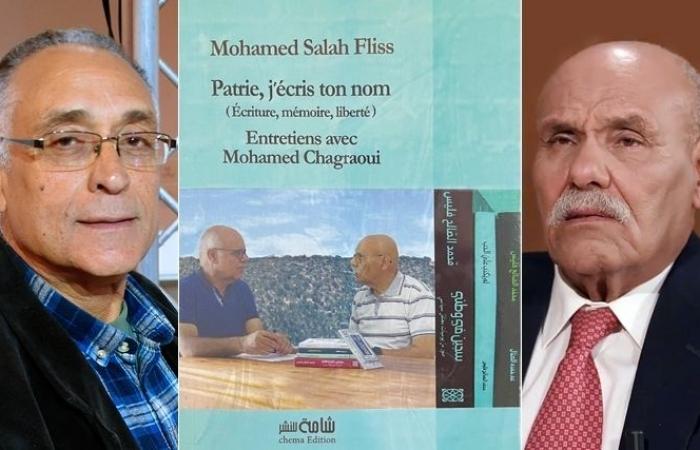

Homeland, I write your name (Scripture, memory, freedom). Interviews with Mohamed Chagraoui, Tunis

Mohamed Salah Fliss

Chema Éditions, 2024, 160 p.

Mohamed Kerrou