Several million deaths, teachers killed by their own students, a leader who incited youth to revolt in order to regain power, state executives forced into exile: the cultural revolution was a unique moment in history. Chinese history between 1966 and 1976, which had a profound impact on the entire world, but also on present-day China. A moment of incredible violence, brought about by Mao Zedong and his armed wing, the Red Guards.

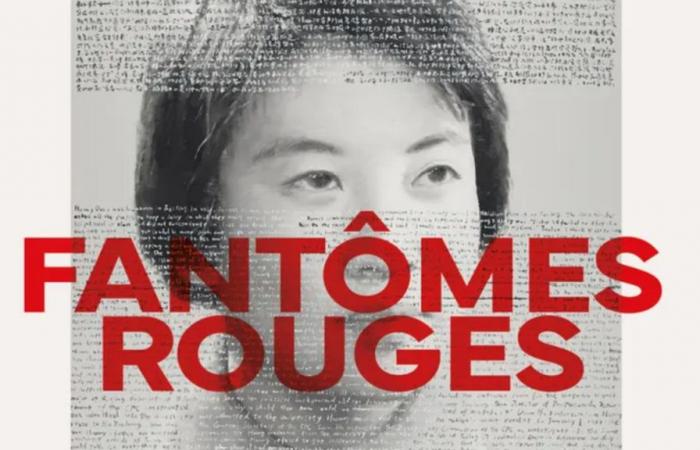

Tania Branigan, former correspondent for the British newspaper The Guardian immersed herself in this decade of “ ideological revolution “. In his book Red ghosts translated into French by Stock (2024), it traces the lives shattered by this decade and questions the ambivalent legacy of this “ revolution » in the Chine of Xi Jinping.

RFI: Hello Tania Branigan. Thank you for accepting RFI’s invitation.

Tania Branigan : Thank you so much for having me on the show.

Why did you choose to write about this subject, the cultural revolution ?

I really don't think I chose the subject, I think the subject chose me. And this is explained by the fact that the cultural revolution is everywhere and nowhere in China. It is not as taboo as, for example, the repression against pro-democracy movements place Tiananmenbut it has always remained a sensitive subject, increasingly monitored. It's there just below the surface, so we're bound to encounter it.

In my case, I was having lunch with a person I knew and during coffee time, she just started telling me that she was going to look for the body of her father-in-law, who was shot during the cultural revolution by Red Guards. And they said that even though they managed to find the village where he had been held, from people who knew him at the time, when they asked where they could find his body, the villagers were completely baffled. They said, “ you know, there were so many corpses at that time, how can you tell which one is yours ».

And during my work as a correspondent in China for The GuardianI found time and time again that the stories I was working on only made sense when placed in the context of the 1960s, because it is such a pivotal period.

You met both victims and Red Guards. How did you react when meeting these elderly people, but who were teenagers when they committed or suffered these crimes?

I think two things are really key. First of all, it is very difficult to think the cultural revolution in terms of victims and perpetrators. That's one of the things that makes this moment so unusual. Many people were both victims and perpetrators. Sometimes some persecuted others, because they were afraid of what might happen to themselves or their families. Or, for the last moments of the cultural revolution, took revenge for the way they had been treated. And because of all the political campaigns, the developments, people could quickly find themselves on the wrong side of history.

Your story is built with key characters, notably that of a composer, Mr. Wang. His life shows how the red lines continue to evolve. Sometimes, his positions earn him strong repression, at other times, they are tolerated. Where are the red lines in today's China?

In the years following the Cultural Revolution, as things opened up, there was an extraordinary intellectual and creative ferment. Obviously, there has never been total freedom: the Party has always sought to control culture, intellectual thought. And this is increasingly the case in recent years, even before Xi Jinping came to power, but very clearly around 2011, 2012, when he took over the country, we saw these topics being increasingly controlled.

The space to discuss ideas, not just political ones, but also social ideals, the way people interact, culture, has become significantly more restricted in China in the last decade.

Some current party cadres, including Xi Jinping's family, were victims of the Cultural Revolution, saw their parents purged, and were themselves sent to the countryside. However, they continue to play with the memory of this moment, allude to slogans of the time and speak of this imagination. What does this moment mean for younger generations? ?

I think a lot of young people don't know much about it. But as you say, what's interesting is that people within the party, and certainly Xi Jinping, have been able to seize on this experience of the Cultural Revolution and some of the nostalgia which surrounds it. And they used that narrative very effectively politically. Since they don't talk about the reasons that led to the Cultural Revolution or the victims, what remains in the collective narrative is the story of Xi Jinping being sent to the countryside to work alongside ordinary people, farmers, able to survive a difficult period. And he talks about that as the moment he became an adult and a man.

The dominant narrative for the majority of Chinese, which is partly true and quite fundamental, is that unlike most Western leaders, here you have a leader who worked the land with ordinary people. He knows life is hard. And he is also someone who has the power to face difficult times. It's obviously a very polished story, but which, I think, still remains convincing for some.