In Ukraine, the war is also being played out in the media. On the Internet, the battle for sovereignty of interpretation rages. War videos play a decisive role in this.

Videos of soldiers at the front or remote-controlled drones destroying a tank. These are images that seem straight out of a video game. Today, anyone can download them in real time from the internet using a mobile phone. This makes the war in Ukraine the first social media war. So how to find your way?

External content

This external content cannot be displayed because it may collect personal data. To view this content you must authorize the category Services Tiers.

Accept More info

Anton Holzer, a photography historian, has written several books on the history of war photography and photojournalism. He warns: “The images of war that we see today only come in a very small part from accredited official photographers. They very often come from soldiers, civilians.” It is therefore important to know the circumstances of the shooting. For example, the time and place where the photos were taken.

Distinguish true from false

This was already the case before the age of social media. During the First World War, the power of impact of war images was already being used. For Anton Holzer, a major media upheaval took place at this time. Photographs from the front became available in large numbers in newspapers. Many photos, for example, show soldiers rushing out of the trenches.

But these were not real battles, explains Anton Holzer: “These images are in no way authentic war images. Most of the photos were not taken on the front line, but during military exercises. However, among the public, these staged images have very often been sold as authentic war images and it is often not easy, after the fact, to distinguish the real ones from the fake ones.

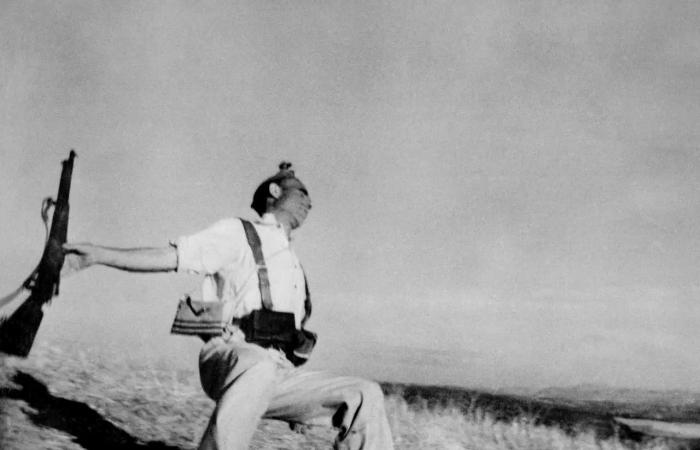

During the Spanish Civil War, photographers took photos in the heart of the action. A first. Until then, photographs were only taken before or after the battle. One of them, Robert Capa, a Hungarian-American photographer whose real name was Endre Ernő Friedmann, went to Spain on his own initiative and without an order, to document the war.

Robert Capa worked according to the following principle: “If your photos aren't good enough, you weren't close enough.” His photos made him a world-famous photographer. The photo “Death of a Republican Soldier” particularly attracted attention. It shows a soldier at the moment of his death. The immediacy of the photo long guaranteed its authenticity, but doubts subsequently arose. He was accused of being staged. Even today, this question is not resolved.

The role of the civilian population

But war is not just about soldiers at the front. Civilians, women and children are also affected. One of the most impressive photos, which immortalizes the suffering of the civilian population, was taken by Vietnamese-American photographer Nick Út. The photo shows a little Vietnamese girl fleeing her village screaming after a napalm attack. In 1972, she was voted press photo of the year.

![The little girl with napalm has become the iconic photo symbolizing the Vietnam War. [KEYSTONE - NICK UT] The little girl with napalm has become the iconic photo symbolizing the Vietnam War. [KEYSTONE - NICK UT]](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/23/c64a7d3315.jpg)

Anton Holzer sees this as a paradigm shift: “Since war has existed and is also reflected in the media, war has been a war of men, a war of soldiers against soldiers. In reality, it is not. has never been, because the civilian population is always part of the war. The same goes for the war in Ukraine. The world reacted with fear to images of the kyiv suburb of Bucha after the departure of Russian troops. Dead bodies lined the streets, some with their hands tied behind their backs. A body was lying on the side of the road, on a bicycle.

![Image of horror in Boutcha, 25 kilometers northwest of the capital kyiv, after the withdrawal of the Russian army. [Keystone / Ronaldo Schemidt - Ronaldo Schemidt] Image of horror in Boutcha, 25 kilometers northwest of the capital kyiv, after the withdrawal of the Russian army. [Keystone / Ronaldo Schemidt - Ronaldo Schemidt]](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/23/970641baf2.jpg)

Anton Holzer is certain that such photographs will one day be used in a legal investigation: “During the Yugoslav War, images played an important role and I am quite certain that – if this war were to end one day – these images of Boutcha will certainly play a role as evidence in court.”

War images are becoming more and more violent

As terrible as these images are, there are countless of them on the Internet. Soldiers in trenches, at which a grenade is thrown by a drone. Corpses devoured by wild animals because no one collected them. Or soldiers who commit suicide out of despair. On social media, like Telegram, control mechanisms disappear, while media companies have guidelines on what they should and should not show.

![Videos are circulating on Telegram showing soldiers being targeted and killed with a drone. [SRF] Videos are circulating on Telegram showing soldiers being targeted and killed with a drone. [SRF]](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/23/ab042d10db.jpg)

This also gives food for thought, says Anton Holzer: “We certainly find these images abominable, cruel, but at the same time we look at them. And then we move on. My requirement would be to look at these images by placing them in their context ( …) We should take these images out of the smartphone and show them for example in a series of printed photos or accompany them with commented notes or perhaps look at them more closely in an exhibition.

The flood of images is beyond us. Like a puzzle, we must represent war from a multitude of images. And it is precisely for this reason that this task seems increasingly difficult today. Added to this are the propagandistic interests of the belligerents. It is therefore all the more important to take a close look.

External content

This external content cannot be displayed because it may collect personal data. To view this content you must authorize the category Services Tiers.

Accept More info

Simon Roth (SRF)