In northern Laos, near the Thai border, scientists are scouring the densely forested hills to collect a surprisingly valuable material: dung from elephants, animals whose numbers have seriously declined in recent decades.

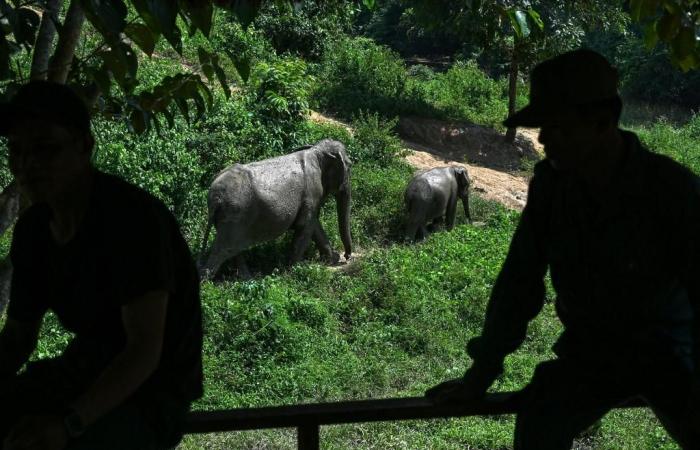

The thirty pachyderms at the Sainyabuli sanctuary, managed by the Elephant Conservation Center (CCE), bear the scars of human violence against wild elephants in Laos.

Asia’s largest land mammal, once abundant in the Southeast Asian country, has suffered from habitat destruction, poaching, abuse from the logging industry and dwindling breeding opportunities . According to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), there are only 500 to 1,000 left in the wild in this small, poor country, compared to three times as many 20 years ago.

To combat this trend, researchers do not hesitate to get their hands dirty and rely on DNA analysis, hoping to improve the species’ chances of survival. Within the Nam Poui protected area, close to the Sainyabuli Sanctuaryscientists are working to collect excrement samples from the 50 to 60 specimens living in the region.

Dung makes it possible to identify individuals, determine their sex, follow their movements and understand the family ties uniting the members of the herd, explains the WWF Laoswhich is collaborating with the CCE on this project.

Establish a genetic reservoir

“The ultimate goal would be to ensure a healthy population of elephants in captivity to serve as a genetic reservoir in the event of a collapse of the wild population,” biologist Anabel Lopez Perez explains to AFP, in her CCE laboratory: “ Once we know the number of individuals present in the country, the final objective will be to put in place an adequate management plan,” she continues.

“Although Nam Poui represents an important habitat for one of the few large populations of wild elephants remaining in Laos, we lack precise data on its composition,” specifies WWF.

At the CCE sanctuary hospital, elephant Mae Khoun Nung places her paw on a wooden structure specially designed to care for elephants. Using a knife, veterinary assistant Sounthone Phitsamone removes the dried mud that has accumulated on her three large nails.

Mae Khoun Nung, 45, spent her adult life in logging until her owner left her to the CCE due to lack of enough work and the high cost of maintaining her.

In 2018, the government’s ban on illegal logging, an industry that used elephants to transport timber, resulted in the animals being sent to work in the tourism sector, while others were sold to zoos, circuses and breeders.

The CCE attempts to purchase and protect captive elephants when they are put up for sale. But many of the people at the center are old and in poor condition after years of hard work, Phitsamone said.

A meager hope

Since 2010, there have been only six pregnancies and three baby elephants.

The trainer, who has worked at the center for more than ten years, has few illusions about the chances of preserving the species in Laos: “If we compare Laos with other countries, the number of elephants in the database is weak, and decreasing,” he says.

“I don’t know if it will be OK in 20 or 30 years. Who knows?” he says.

afp/sjaq