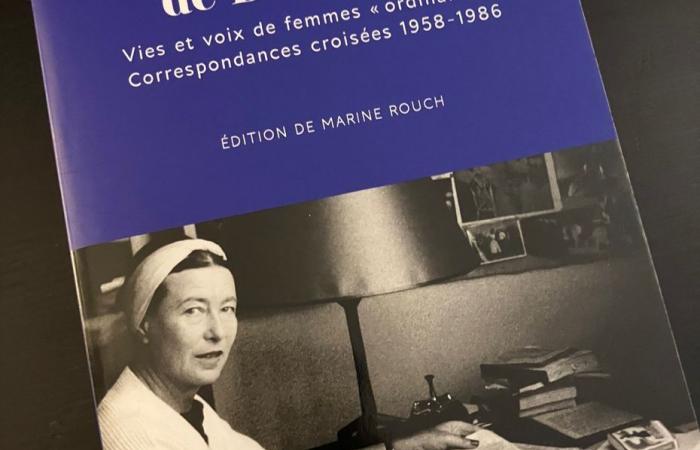

Marine Rouch, historian of feminisms and gender, traces, through five women in construction, the relationship of the philosopher with her readers. A real correspondence and mutual enrichment. Not simple idolatry on the one hand and pale conventions to meet one’s obligations on the other.

The essentials of the day: our exclusive selection

Every day, our editorial team reserves the best regional news for you. A selection just for you, to stay in touch with your regions.

France Télévisions uses your email address to send you the newsletter “Today’s essentials: our exclusive selection”. You can unsubscribe at any time via the link at the bottom of this newsletter. Our privacy policy

“It was the 2013-2014 academic year, I was starting a research Master’s degree in contemporary history at the University of Toulouse, and I had chosen to work on the reception of the “Second Sex”, reading which had made me upset. » Thus Marine Rouch explains the start of her approach, from the first lines of her work. But her field of research will extend, to include a whole correspondence (20,000 letters) from women with the writer who, during her lifetime, was already a “star”.

Unlike Sartre, De Beauvoir does not have a secretary. Which will not prevent her from responding to all these reader-correspondents. Some missives were lost, others have not yet been found, from 1950 to 1986, the date of the left-wing intellectual’s death. But the essential is there through these five young women chosen by Marine Rouch: “writing to Simone De Beauvoir is an integral part of their intellectual training and their true quest for self”.

In the same way that these readers felt close to Simone de Beauvoir, I too, over the months and then the years, developed a feeling of familiarity, sometimes bordering on identification, with some of her most intimate correspondents. diligent. I too wanted to write to them, to talk to them, to see their faces

And it was worth it. From the first chapter, Blossom Margaret Douthat’s passionate missives clearly show that these selected writings are not junk or stylistic effects but indeed commitments. The young American who will grow up to reflect Beauvoir, in her life as a woman and “thinker of the revolution”, has things to say to the philosopher. And she will always do it with her guts and not necessarily with tact.

Mireille Cardot was a high school student in the Paris region when she began writing to de Beauvoir. Her candor is touching almost as much as the unfeigned kindness of the left-wing intellectual towards her.

Recently, I read the first volume of The Second Sex which fascinated me. Of course, there are certain pages of philosophy that I haven’t understood (sic) because I haven’t taken philosophy yet (I’m sixteen and I’m in my first year) and I’m waiting for the year next time looking forward to it.

It’s very nice what you say to me and I find it remarkable that at this age you have read so much. I hope that the baccalaureate goes well, and that next year philosophy will interest you: if you have a good teacher, you must be passionate about it. I would like to know what has become of you. I have a lot of sympathy for you.

However, the reader should not expect great dissertations from de Beauvoir. Most of his answers are just a few lines long. But what matters here is the effects that these epistolary exchanges will have on the women who write to him. They also give their names to the chapters: “thinking and living the revolution”, “the intellectual training of a young girl”, “going through the torments of adolescence”, “the resumption of a destiny through freedom” and “you made me as I am.”

“This frayed friendship that I have with you seems more alive to me than any other,” confesses to the philosopher Claire Cayron, raped by her “erotomaniac” husband. And the latter also confided to him that “perhaps he drugs me too without me realizing it”. A sentence that resonates more than ever in view of the trial of the year which has just ended.

If only sadness, a lugubrious air came out of you, it will be a long time since I would have (sic) any pleasure in exchanging ideas with you when in fact forty years separate us.

Whether it is the book on divorce by Claire Cayron or the articles for the magazine “Modern Times” by Céline Bastide, Simone de Beauvoir pushes her interlocutors to write. “To write for me is to succeed in being me” says Céline Bastide who will also say to the philosopher: “you made me who I am today.” A sentence that sums up well the impact she had on her correspondents.

Marine Rouch ends her preface thus: “The intimacy revealed in these letters inevitably echoes mine. I recognize myself in each of his women.” No doubt other women will recognize themselves in it too.