In some ways, Captagon is the great unifier of the drug world.

The synthetic stimulant is used across the Middle East by everyone from truckies and taxi drivers battling through shift work, to high-powered executives looking to party, to militia fighters searching for some “chemical courage”.

Dubbed the “poor man’s cocaine” but also a party drug for the rich, it was even found among the belongings and vehicles of Hamas terrorists during the October 7 attacks on Israel.

And until this week, it was said to be the number one export in Syria’s zombie economy.

The tiny white pill has done untold damage across the region and propped up the brutal regime of ousted Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, allowing it to become one of the world’s biggest drug syndicates.

But the unexpected and rapid collapse of that so-called “narco-state” now raises serious questions about the industrial-scale drug trade that helped them survive for this long.

And some experts are warning about what comes next.

The little pill of ‘chemical courage’

Captagon was the name of a drug first developed in the 1960s by a German pharmaceutical company.

It was used to treat depression and hyperactivity, until it was banned by regulators in the 1980s due to the risk of abuse.

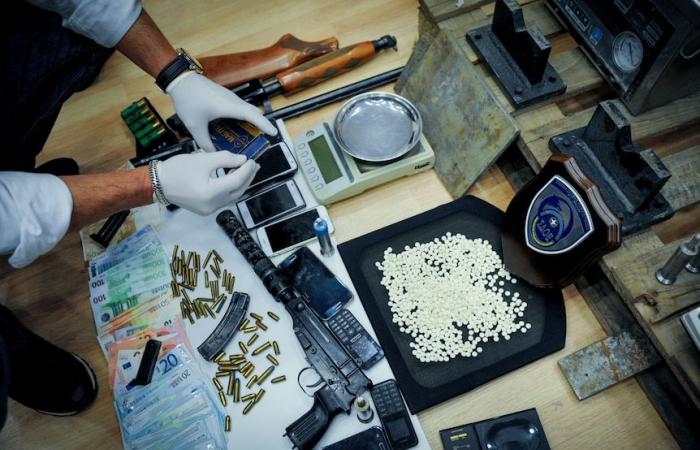

Captagon is said to give the user a feeling of well-being, euphoria and invincibility. (Reuters: Nikolay Doychinov)

Manufacturers in the Middle East then started developing a knock-off version, but it really took off in about 2011, thanks to the Syrian war and the collapse of the economy in neighbouring Lebanon.

Strangled by international sanctions, the Syrian regime led by Bashar al-Assad ramped up production of Captagon to an industrial scale.

The New Lines Institute, a Washington-based think tank, estimated the global market for the drug was about $US5.7 billion ($8.9 billion), with the Assad regime raking in about $US2.4 billion annually.

Institute director Caroline Rose said the Captagon trade played a vital role in offering a lucrative revenue stream to the Assad regime to fund the war.

“Captagon certainly played that role in trying to buffer and keep the Syrian regime — but not necessarily the Syrian economy — afloat,” she told the ABC.

“Additionally, it provided leverage for the Syrian regime. It was a key negotiation tool that they were able to bring out around discussions revolving around normalisation.”

Captagon has spread across the Middle East and Europe, in part because of the Assad regime’s trafficking efforts. (Reuters: Michalis Karagiannis)

Indeed, regional players including Iraq, Jordan and Saudi Arabia normalised relations with the Syrian government last year in return for Assad pledging to crack down on Captagon.

While it initially appeared to be working, the Captagon trade has continued to flourish since then.

The Middle East is awash with Captagon

The wave of drugs flooding out of Syria has been a disaster for the region.

Captagon has become a public health crisis in the Middle East and caused skyrocketing levels of addiction, particularly across the wealthy Gulf states, where alcohol is restricted or banned.

Regular use can cause insomnia, depression, hallucinations and heart problems.

It’s also been used by some militia fighters and terrorists for the feeling of invincibility and emotional detachment it can bring, which some describe as “chemical courage”.

Armenak Tokmajyan, a scholar at the Malcolm H Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut said Captagon had a significant impact on places such as neighbouring Jordan.

“Jordan has long served as a transit route for drugs heading to the wealthy Gulf countries,” he told the ABC.

Syria’s regime is blamed for the rise of Captagon abuse across the region. (Getty Images: Thierry Monasse)

“But in recent years it has also become a market for narcotics, including Captagon.

“Having visited northern Jordan myself, I have witnessed firsthand the repercussions this has had on local communities.”

What happens next?

With the Assad regime gone, questions loom over the future of the lucrative and illegal Captagon industry.

During rebel leader Abu Mohammed al-Golani’s victory speech in Damascus earlier this week, he made reference to Assad’s Syria having “become the world’s leading source of Captagon”, vowing to “purify” the country.

Abu Mohammed al-Golani vowed to “purify” the country of Captagon. (AP:Omar Albam)

Caroline Rose from the New Lines Institute said she doesn’t expect a complete end to the Captagon trade in the country, despite the promises of the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leader.

“It’s very clear that HTS is going to try to distance itself from Captagon production and trafficking,” she said.

“And I do think this does bring an end to Syria and its role as a narco-state.”

“That doesn’t mean there won’t be corruption, that there won’t be a few different affiliations but when we look at it from a systematic level, we won’t see what we saw with the Syrian regime.”

Mr Tokmajyan agreed it would be a major challenge for the incoming Syrian leadership.

“Any future ruler of Syria will inevitably face the challenge of addressing this issue, which involves dismantling production facilities, disrupting distribution channels, and dismantling smuggling networks,” he said.

Syria’s drug empire has affected many countries around the region, including Yemen. (Getty Images: Mohammed Hamoud)

“Al-Golani is signalling his willingness to take on this task. If leadership falls to him, he would likely see it also as a religious obligation to combat this illicit trade, given his ideological stance.”

But Dr Oscar D’Agnone, medical director of drug and alcohol treatment centre the OAD Clinic in London, which treats captagon users from the Middle East, is worried about what will happen in the meantime.

“What I would expect is in the coming weeks, Captagon will be more available in many places,” he said.

“For the people from the militia, governmental and even insurgent groups, these drugs are like cash in hand and they will try to cash out straight away, so this is why I think it will come to Europe straight away.

“It’s going to be a temporary thing but it could be dangerous.”