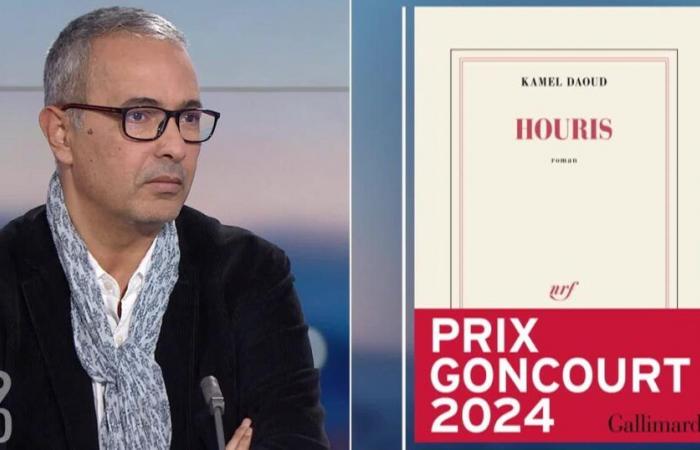

In “Houris”, winner of the 2024 Goncourt Prize, the writer Kamel Daoud examines the “black decade” which tore Algeria apart in the 1990s. Guest of RTS, he recounts the process of “return to life” which accompanied, for twenty years, the birth of this novel.

A young journalist for the conservative French-speaking newspaper Le Quotidien d’Oran at the start of the Algerian civil war (1992-2002), Kamel Daoud covered mass massacres and counted the dead. “At that time, almost all journalists did what we call security coverage. It was everyday life, there were massacres every day and everywhere in the country. It was something that concerned everyone “, he says on Sunday in the 7:30 p.m.

More than twenty years after the end of this conflict, which left between 60,000 and 200,000 dead, according to different estimates, it is through literature that the 54-year-old Franco-Algerian gives voice, in “Houris” , to the suffering linked to this dark period, that of women in particular.

>> Read also: Kamel Daoud receives the Goncourt prize with “Houris” and Gaël Faye le Renaudot with “Jacaranda”

Writing against prohibitions

“We need distance, time also to mourn a period and be able to give a story, to be able to tell it. I meet a lot of Algerians in France and in Europe who are very moved when they buy the book, because it also tells their story,” he explains.

The ban creates desire (…) But beyond that, I think that Algerians need to hear this story told.

“Houris” could not be exported to Algeria and even less translated into Arabic, because Algerian law prohibits any mention of the bloody events of this period. “Writing does not obey prohibitions”, however, underlines Kamel Daoud. “There are Algerians who have written about this period and I have just written about it, so it is something that exists. I think we cannot stop the process of awareness, despite the legal ban .The work will be done.”

And for good reason: the book is already circulating a lot in Algeria. “The ban creates desire, envy and attracts a lot of people, it’s an old story of humanity. But beyond that, I think that Algerians need to hear this story told .”

All over the world, there are generations who tell the next generation nothing about a war

However, “it is not a novel of war or despair, it is a novel of returning to life”, continues the author. “It’s a novel that answers the question: is there life after the dead? Yes, there is life possible. So it’s a novel of hope.”

>> The portrait of Kamel Daoud in the 7:30 p.m.:

A raw reality impossible to narrate

To construct this very harsh story, Kamel Daoud confides having lightened a large majority of the horror scenes in order to preserve a certain “threshold of tolerance” among his readership. “I think that the real, brutal, raw, it is impossible to narrate,” he justifies.

We forgive men for having killed but we never forgive women for having been dishonored

“What I tell in this novel are true stories. I have amalgamated characters who really existed. But the story of war is always hard, it’s not something easy to tell. Throughout the world, there are generations who tell the next generation nothing about a war.”

The author, already awarded a Goncourt for first novel in 2015 for “Meursault, contre-investigation”, chose to tell the tragedy through a female voice. “Because it’s women who pay for wars. We all know that,” he explains. “We forgive men for having killed and we never forgive women for having been dishonored, for having been raped, for having become pregnant outside of marriage.”

“We saw it, even in the great decolonial epics, when we had independence, we asked women to return to the kitchens. Whatever we say, women pay the price for our freedoms,” insists he. “And in societies where women are not free, we no longer have freedom for the rest.”

>> Also listen to the section Aloud dedicated to Kamel Daoud:

Comments collected by Fanny Zuercher

Web text: Pierrik Jordan