« We know that carbon is necessary for the formation of rocky planetsrocky planets and solar systems like ours. It’s exciting to get a glimpse of how star systems binarybinary not only create carbon-rich dust, but also propel it into our galactic neighborhood “, explains in a press release from NASA Jennifer Hoffman, co-author of an article published in Astrophysical Journal Letters and professor at the University of Denver. The astrophysicist and her colleagues have just brought Wolf-Rayet 140 back into the spotlight, a star that researchers have been studying for a while now, most recently with the instruments of the space telescopespace telescope James-Webb (JWSTJWST). This is a binary systembinary system already studied with the Hubble telescope and which is located at around 5,600 light yearslight years of the Solar System in the Milky Way when looking in the direction of the constellationconstellation of the Swan.

In previous articles on it, Futura had already explained that just like the Hubble telescope, the JWST could make contributions to many questions ofastrophysicsastrophysics and of cosmologycosmology. They are not limited to the study of the first galaxiesgalaxies or the analysis of the chemical composition of atmospheresatmospheres d’exoplanetsexoplanets. We know, for example, that the interstellar dustinterstellar dust making up approximately 1% of cloudsclouds Dense, cold molecules are a key ingredient in the formation of stars and planets. However, it turns out that the various processes of production of this dust are not yet as well understood as cosmochemists and astrophysicistsastrophysicists would like it.

Did you know?

Wolf-Rayet stars have been known since 1867. They were discovered, as their name suggests, by Charles Wolf and Georges Rayet, of the Paris Observatory, by observing three stars in the Cygnus constellation to carry out studies relating to of a very young discipline then in full development following the work of the German physicist Gustav Kirchhoff and the chemist Robert Bunsen: spectroscopy.

These stars appeared to be anomalous due to the presence of strange spectral emission lines of unknown origin. Astrophysicists of the 20th centurye century will understand that WR stars are massive stars exceeding 10 solar masses that we observe at the end of their life while instabilities lead them to expel part of their upper layers, as a prelude to explosions in SN type supernovae II.

They therefore only live for a few million years at most on the main sequence, synthesizing elements, such as carbon and oxygen, before collapsing gravitationally. The explosion will then leave a neutron star as a stellar corpse and, for the most massive stars, sometimes stellar black holes.

This is why, to see things more clearly, programs for studying double star systems known as Wolf-Rayet (WR) binaries ventsvents in collision were underway with the JWST. They are, in fact, efficient dust producers in theUniverseUniverse current local and above all, it is believed, representative examples of other colliding wind binaries that probably existed in early galaxies.

It has been known for decades that WR 140 is a massive double star comprising a Wolf-Rayet star of type WC7 and an O5 star, probably a blue supergiantblue supergiant. Both stars blow fast stellar winds (around 3,000 km/s) under the effect of radiation pressureradiation pressure produced by luminositiesluminosities out of 103 at 104 times that of SoleilSoleil. Which therefore leads to losses of massemasse significant, approximately 10-5 et 10-6 solar masses/year.

Giant dust bubbles

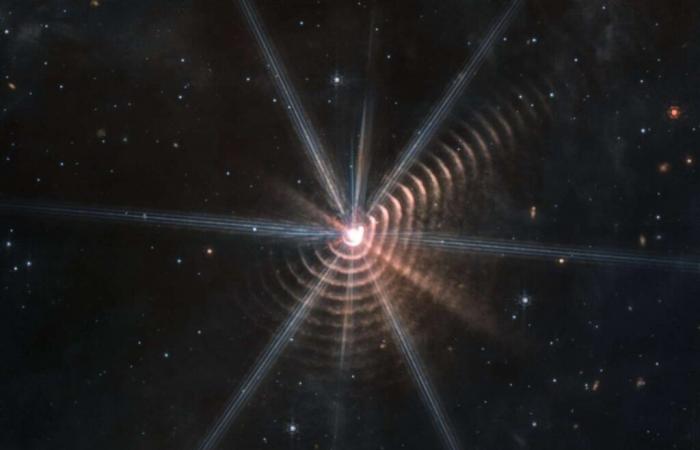

Recent JWST images are fake colorscolors because taken in theinfraredinfrared. They exhibit the eight branches produced by the phenomenon of diffractiondiffraction with the mirrorsmirrors of the telescope (see on this phenomenon, the cult work on optics by Eugene Hecht). It is therefore an artifact, but this is not the case for the series of circular arcs surrounding the central binary in these images.

These are shells of gazgaz which appear as rings because the edges of these shells, which are not perpendicular to the observer’s view, represent the radiation of “columns” of mattermatter thicker on the line of sight.

The existence of these shells is not mysterious and it is understood how they are produced periodically every 7.94 years or so. About 20 rings are visible and, according to astrophysicists, the youngest was born in 2016. But how do they know?

This animation shows dust production in the binary star system WR 140 as the orbit of the Wolf-Rayet star approaches the O-type star and their stellar winds collide. Stronger winds from the Wolf-Rayet star blow behind the O star, and dust is created in its wake as the mixed stellar material cools. As the process repeats, the dust will form a shell. © NASA, ESA, and J. Olmsted (STScI)

The determination of the orbital parameters of the stars of WR 140 shows that they are on orbitsorbits respective enough eccentricseccentricsso that they come together in a consistent way by reaching for one of them its periastreperiastre (the shortest distance separating them) approximately every 7.94 years.

The collision between the stellar winds produced by the two stars is quite violent at this time, and a bubble of expanding material is then born, which as it cools will cause dust to condense. It is these dusts which are heated by the radiation ultravioletultraviolet of the two young massive stars will then cool by radiating in the infrared, revealing the expanding shells when viewed by the JWST. We can thus see kinds of stratastrata testifying to the past history of about 160 years of the binary.

This video alternates between two James Webb Space Telescope observations of Wolf-Rayet 140, a two-star system that has emitted more than 17 dust shells in 130 years. Observations in mid-infrared light highlight them with excellent clarity. By comparing these two observations, taken just 14 months apart, the researchers showed that the dust in the system has spread. All the dust in each shell moves at almost 1% the speed of light. The stars are very bright, which led to the diffraction peaks in both images. These are artifacts, not significant features. © Joseph DePasquale; Space Telescope Science Institute, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, European Space Agency, Canadian Space Agency

Dust shells that expand at more than 2,600 kilometers per second!

The NASA press release specifies that the stellar winds of each star in the WR 140 binary collide periodically (for several months every eight years), so that matter is compressed and carbon-rich dust is formed. Webb’s latest observations show 17 dust shells glowing in mid-infrared light and therefore expanding at regular intervals into the surrounding space at more than 2,600 kilometers per second.

Which leads Emma Lieb, lead author of the new paper and a doctoral student at the University of Denver, Colorado, to say that JWST “ not only confirmed that these dust shells are real, but his data also showed that the dust shells move outward at speedsspeeds constant, revealing visible changes over incredibly short periods of time “, which also makes Jennifer Hoffman say that ” we are used to thinking that events in space unfold slowly, over millions or billions of years. In this system, the observatory shows that the dust shells expand from one year to the next ».

These shells can persist for more than 130 years, so over the life of WR’s star, tens of thousands of dust shells (each as small as one-hundredth the width of a human hair ) over hundreds of thousands of years will emerge.

We know in fact thanks to the theory of evolutiontheory of evolution stellar well corroborated by observations that stars at least 10 times more massive than the Sun can only live a few million years at most before exploding into supernovasupernova leaving as a stellar corpse a neutron starneutron star or a black holeblack holeor even implode directly into a black hole.

Excerpt from the documentary From the Big Bang to lifeassociated with the site of the same name, a French-speaking multiplatform project on contemporary cosmology. Jean-Pierre Luminet talks about the death of massive stars, their explosion as supernova and the formation of pulsars. © ECP Productions, YouTube