Tarsila do Amaral was born in 1886 on the family plantation, two years before the abolition of slavery in Brazil. She belongs to the social class of coffee barons from the state of São Paulo, where her grandfather, nicknamed “the millionaire”, does not have less than 22 farms, or agricultural properties. Tarsila received the education of a young girl from the upper bourgeoisie, she painted and played the piano. The French-speaking world is in tune with the times; she reads Victor Hugo in the text and sings The Marseillaise under the direction of his Belgian tutor.

A cosmopolitan youth of the Roaring Twenties

The family travels and, at the time, travel means Europe, where Tarsila stays for two years at a boarding school in Barcelona. She was only 18 when, on her return, she was married to a distant cousin with whom she had a daughter, Dulce, in 1906. Thanks to the financial support of her father and despite the opposition of the rest of her family, she separated from her husband in 1913 and settled in São Paulo. Having ended an unhappy marriage, Tarsila decided at the age of 29 to devote herself to painting. She took classes with academic painters and took the plunge in 1920 by leaving for Paris, the capital of the arts, where she enrolled at the Académie Julian.

Portrait of Tarsila do Amaral in the 1920s, private collection ©AKG_Images/Heritage Images.

However, the shock of modernity happened to him in São Paulo in 1922, where the protagonists of the “Modern Art Week” had just overturned established values. “Contaminated by the revolutionary ideas of the euphoric and biting Paulista avant-garde”as she confided in 1950, she returned to Paris at the end of 1922, choosing her teachers who this time were named André Lhote, Fernand Léger and Albert Gleizes.

A caipirinha dressed as Poiret

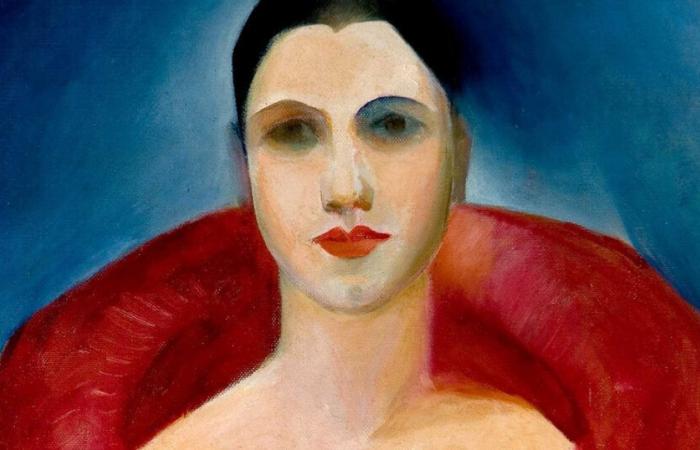

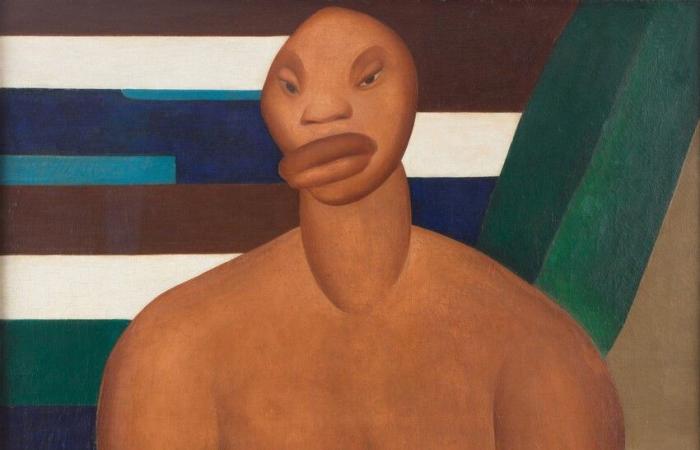

Described thus by her new companion, the Brazilian poet Oswald de Andrade (1890-1954), Tarsila, beautiful, cultured and elegant, mixed with the Parisian avant-garde, organizing at her home, rue Hégésippe Moreau in the 18th arrondissement, brilliant meetings where we meet Blaise Cendrars, Constantin Brancusi, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Pablo Picasso and Léonce Rosenberg. One foot in Paris where, in the midst of primitivism, its exoticism seduces and one foot in Brazil, where her knowledge of the Parisian avant-garde fascinates, Tarsila takes advantage of her situation and develops a unique visual language, a synthesis between a nascent Brazilianness and a modern cubist alphabet. With a stylized banana leaf in the background for any decor, The Black (1923) thus depicts, using tubular shapes, a former black slave.

![Tarsila do Amaral,<i>The Black Girl [La Négresse]</i>, 1923, oil on canvas, 100 x 81.3 cm, São Paulo, Mac-Usp. ©R. Vials.” class=”size-medium wp-image-197384″/></p> <p id=](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/11/355e1ecc0d.jpg) Tarsila do Amaral, The Black [La Négresse]1923, huile sur toile, 100 x 81.3 cm, São Paulo, Mac-Usp. ©R. Fialdini.

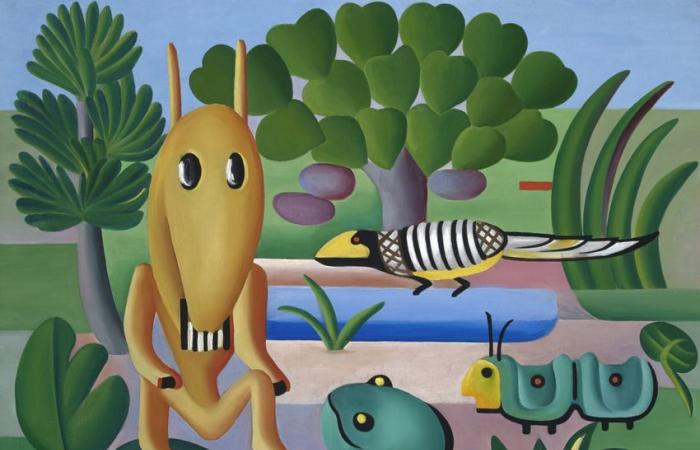

Tarsila do Amaral, The Black [La Négresse]1923, huile sur toile, 100 x 81.3 cm, São Paulo, Mac-Usp. ©R. Fialdini.Both extremely wealthy, in love and in intellectual synergy, Tarsila and Oswald embarked in 1924 on a series of trips to Brazil which further expanded their vocabulary, then in 1926 they traveled to Greece, Turkey, Israel and Lebanon. That same year, a first personal exhibition of Tarsila's works, in frames by Pierre Legrain, opened in Paris at the Percier gallery. For the artist, it is a consecration. His work To cuck (1924) representing an exotic and imaginary bestiary, enters the French national collections. Back in Brazil, Tarsila painted in 1928 Abaporu, which means in the indigenous Tupi-Guarani language “man who eats another man”, and which she gives to Oswald for his birthday. Among the artist's most emblematic works, the painting inspired Oswald to Anthropophagous manifestoa founding text of Brazilian modernity that he published a few months later, with the only illustration being a drawing of Tarsila depicting this character with an enormous foot and tiny head.

Academia N°4 (1922) and Figura em Azul (1923) by Tarsila do Amaral, presented in the exhibition “Tarsila do Amaral. Painting modern Brazil”, Luxembourg Museum, Paris, 2024 © Connaissance des Arts / Guy Boyer

Crossing the desert

In the summer of 1929, Tarsila, at the height of success, exhibited for the first time in her country, in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, where she also presented the jewels of the personal collection she had built in Paris. . The amazed public discovers original works by Brancusi, De Chirico, Delaunay, Léger, Lhote, Miró, Picabia and Picasso. The following autumn resembles a cataclysm. The New York stock market crash leads to the collapse of coffee prices. His family is ruined, the properties mortgaged. At the same time, Oswald falls in love with a young writer, Pagù, and the couple separates.

![Tarsila do Amaral,<i>The Bull (Ox in the forest) [Le Taureau (bœuf dans la forêt)]</i>, 1928, huile sur toile, 50.3 x 61 cm, detail, Salvador de Bahia, Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia ©R. Fialdini.” class=”size-medium wp-image-197391″/></p><!-- Composite Start -->

<div id=](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/11/e8df648ebf.jpg)

At 44, Tarsila has to change her lifestyle and for the first time, work to support herself. She briefly held a position as curator at the São Paulo Pinacoteca and began writing columns for the newspaper « São Paulo Diary »(between 1936 and 1954). She continues to paint but now has to respond to commissions. The world is changing and so is Tarsila. With her new companion, the psychiatrist and left-wing intellectual Osório César (1895-1979), she made a trip to the Soviet Union in 1931 which delighted her, selling part of her collection to finance the expedition. On her return, the constitutionalist revolution broke out in São Paulo, but President Getúlio Vargas remained in power and Tarsila was imprisoned for a month because of her recent trip to the USSR.

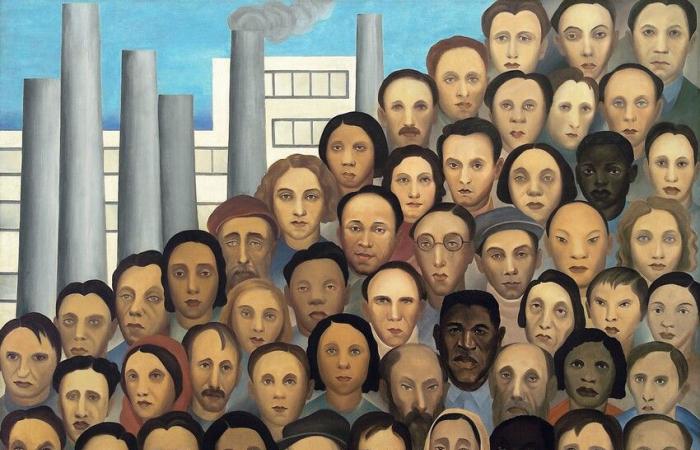

![Tarsila do Amaral,<i>Workers [Ouvriers]</i>, 1933, huile sur toile, 150 x 205 cm ©Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Palaces of the Government of the State of São Paulo/R. Fialdini.” class=”size-medium wp-image-197388″/></p> <p id=](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/11/96db24aa16.jpg) Tarsila do Amaral, Workers [Ouvriers]1933, huile sur toile, 150 x 205 cm ©Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Palaces of the Government of the State of São Paulo/R. Fialdini.

Tarsila do Amaral, Workers [Ouvriers]1933, huile sur toile, 150 x 205 cm ©Artistic-Cultural Collection of the Palaces of the Government of the State of São Paulo/R. Fialdini.The new social consciousness that drives him can be read in his paintings, whose iconography and style are tinged with socialist realism with Workers (1933), change. In 1933, she separated from Osório César and met the writer Luís Martins (1907-1981), twenty-one years her junior, with whom she maintained a relationship until 1951. In the 1940s, she tackled a new dreamlike style, where disproportionate characters merge with nature. Tarsila, who continued to participate in group exhibitions, had to wait until the 1950s for real critical work to be carried out on her work. The retrospective organized in 1950 at the Museu de Arte Moderna in São Paulo put her back in the spotlight.

![Tarsila do Amaral, <i>A Cuca [La Cuca]</i>, 1924, oil on canvas, 60.5 x 72.5 cm, detail ©Grenoble, musée de Grenoble/ JL Lacroix.” class=”size-medium wp-image-197383″/></p> <p id=](https://euro.dayfr.com/content/uploads/2024/12/11/9e04f98990.jpg) Tarsila do Amaral, Cuckoo [La Cuca]1924, oil on canvas, 60.5 x 72.5 cm, detail ©Grenoble, musée de Grenoble/ JL Lacroix.

Tarsila do Amaral, Cuckoo [La Cuca]1924, oil on canvas, 60.5 x 72.5 cm, detail ©Grenoble, musée de Grenoble/ JL Lacroix.The following year, she was chosen to represent Brazil at the first São Paulo Biennale. At 66, Tarsila is finally recognized as a major figure of Brazilian modernism. Having become paraplegic following a spinal operation, her end of life was overshadowed by the death of her daughter Dulce in 1966. She nevertheless attended the inauguration of the major retrospective dedicated to her by the Museu de Arte Moderna of Rio de Janeiro and the Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo in 1969, before passing away on January 17 1973.

The advantages of the exhibition

With the ambition of making known a modern star artist in Brazil and practically unknown in France, the exhibition embraces her entire career without ignoring the final period, from the 1940s to her death. Chronological, the tour contextualizes the work in the Brazilian natural and urban landscape of the time, thanks to large photographic enlargements.

The least

Abaporu (1928) did not make the trip from Buenos Aires. Emblematic, the work can be discovered at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires. Purchased by an Argentinian collector, Eduardo F. Costantini, for $2.5 million in 1995, the painting was given to the museum in 2001. The museum usually refuses to part with this Mona Lisa of modern South American art.

Right: Paysagem con cinq casas (1965), presented in the exhibition “Tarsila do Amaral. Painting modern Brazil”, Luxembourg Museum, Paris, 2024 © Connaissance des Arts / Guy Boyer