In recent years, several exhibitions have been devoted to legendary liners, focusing on decorative arts and the Art of living. Very different, this one adopts a double point of view: the liner as a modernist object, a source of inspiration for architects, painters, poster designers, avant-garde photographers, and the experience of travel aboard transatlantic ships in the interwar period, focusing mainly on the most spectacular of them, Normandieinaugurated in 1935.

A source of inspiration for artists

« The adventure of ocean liners covers a century of history, from the 1860s to France of 1962. Our discussion focuses on a narrow period, from 1913, the year when the Armory Show opened in New York, the first major international exhibition of modern art in the United States, to 1942, the date of fire that devastates Normandie in Manhattan Harbor », explains Sophie Lévy, director of the Nantes Arts Museum.

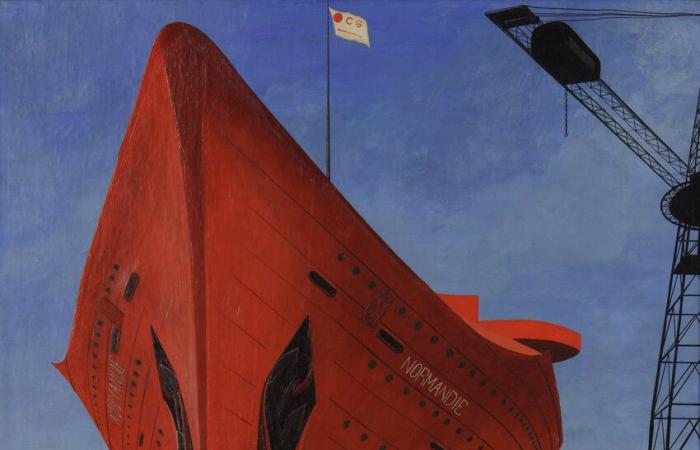

In an elegant blue and white scenography, the first part shows how the artists seize the silhouette, volumes and lines of liners to give birth to a new aesthetic. At a time when tourism is developing, competition is fierce between French, English and German companies, etc., who are seeking the best poster artists to promote their ships. In the majority of cases (Paul Colin, Albert Fuss, etc.), the bow fills the space, seen from three quarters and from a low angle to reinforce the effect of monumentality. In his iconic poster for NormandieCassandre is one of the only ones to choose frontal vision, with perfect symmetry.

The poetics of the machine

The liner stimulates the imagination of architects. Le Corbusier – including an unrealized project for Île-de-France is presented in the exhibition – considers that it embodies a rational and modern way of living. After the Second World War, he took inspiration from it to develop his Radiant Cities. The La Pergola casino, built in Saint-Jean-de-Luz by Robert Mallet-Stevens in 1928, the Latitude 43 hotel by Georges-Henri Pingusson in Saint-Tropez in 1932, Villa E-1027 by Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin (1926-1929), with its passageways, its roof terrace, its functionalist fittings and its armchairs Deckchairare emblematic of what we will call the “liner style”.

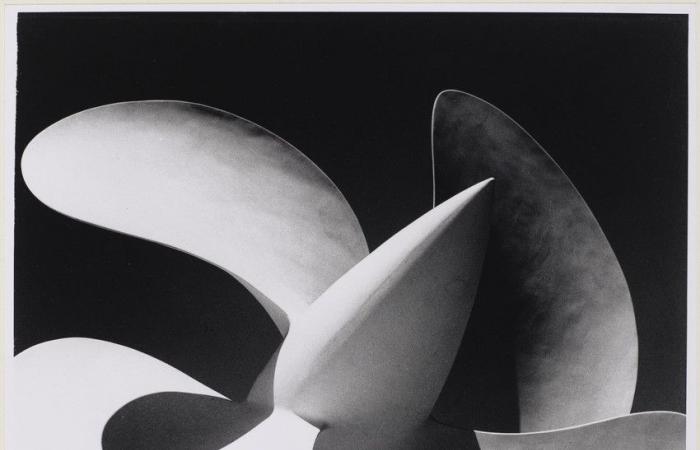

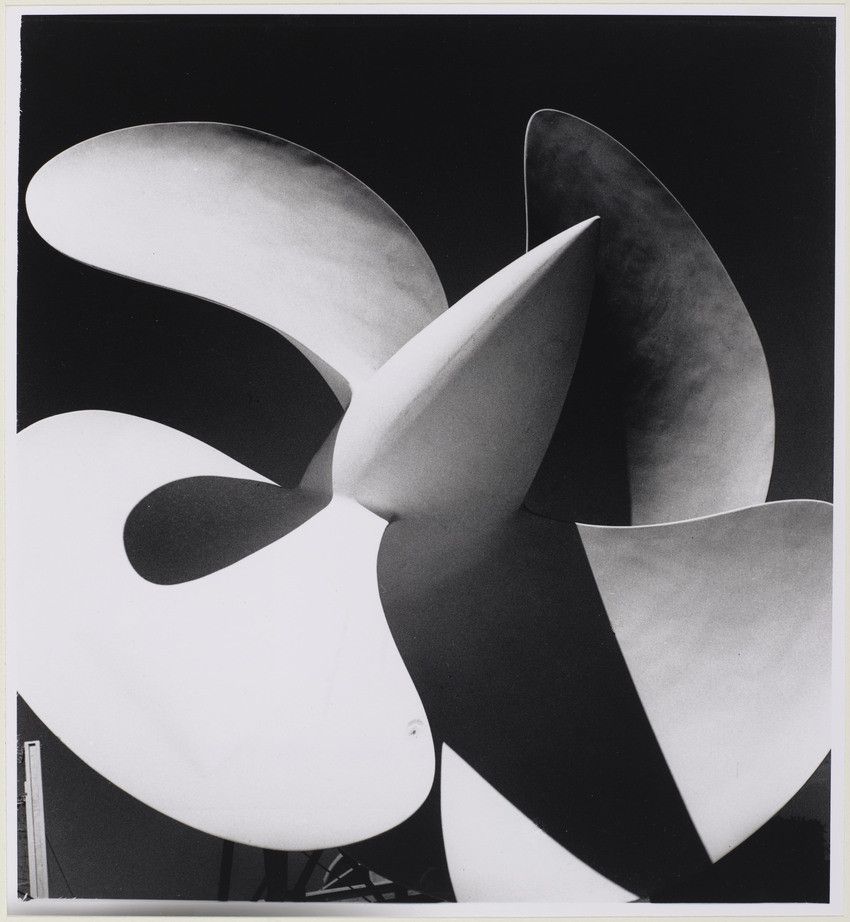

Pierre Boucher, Normandy propeller at the Paris Universal Exhibition1937, gelatin silver print, period print, 33 x 30.3 cm. Paris, Center Pompidou – National Museum of Modern Art – Center for Industrial Creation © Center Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Audrey Laurans

Pierre Boucher, Normandy propeller at the Paris Universal Exhibition1937, gelatin silver print, period print, 33 x 30.3 cm. Paris, Center Pompidou – National Museum of Modern Art – Center for Industrial Creation © Center Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Audrey LauransIn photography, gigantism induces truncated framing, high points of view (from the cranes of the Penhoët shipyards, in Saint-Nazaire, where a number of units like Provence, Paris, The Atlantic…) or, from the quay, at the foot of the giants. From André Kertész to Walker Evans, from Jean Moral to Roger Schall and François Tuefferd, the big names in modern photography focus on certain details, in an aesthetic of the fragment, in close-up. Chimneys, fans, propellers, ropes, chains… everything becomes a subject, right up to the boundaries of abstraction.

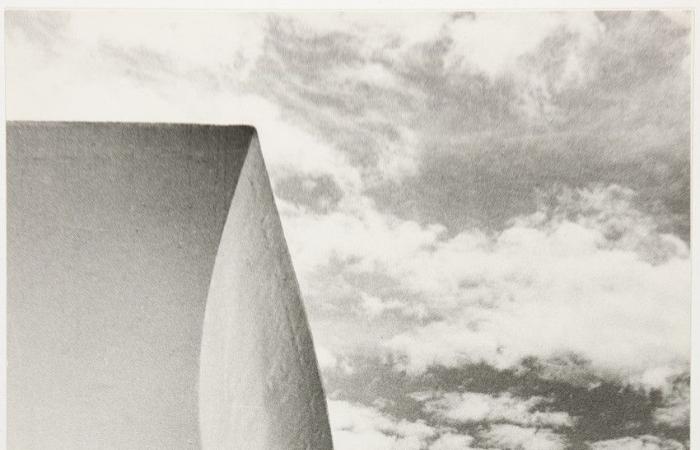

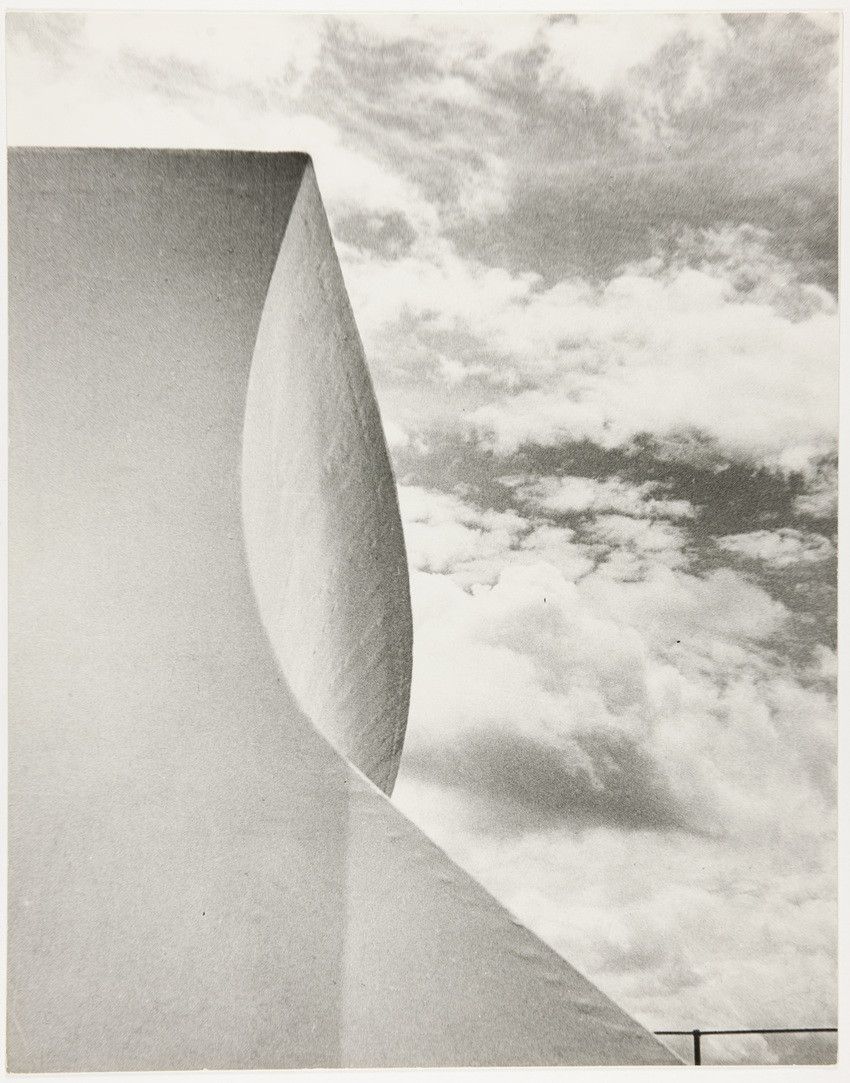

François Tuefferd, Bow of Normandy1936, black and white gelatin silver print on Agfa satin paper (1985 print), 34 x 26.7 cm. Nantes, Nantes Arts Museum © Nantes Arts Museum, photo: C. Clos.

François Tuefferd, Bow of Normandy1936, black and white gelatin silver print on Agfa satin paper (1985 print), 34 x 26.7 cm. Nantes, Nantes Arts Museum © Nantes Arts Museum, photo: C. Clos.The same goes for painting. In his representations of Normandie under construction, Jules Lefranc draws direct inspiration from photographic framing. Fascinated by the modern world and the machine, Fernand Léger draws from the world of ocean liners a graphic vocabulary which nourishes post-cubist compositions, structured by stylized interlocking shapes, energized by colorful contrasts (The Tugboat Bridge from 1920, a masterpiece of the genre on loan from the Center Pompidou).

Inspired by Orphic Cubism and Futurism, American precisionists Charles Demuth and Victor Servranckx simplified the pattern even more radically. The first suggests the Paris liner (1921-1922) by two red chimneys, a network of obliques and tubular shapes which breathe movement. In his masterful Port. Opus 2 (1926), the second summarizes the ship in a repertoire of signs – the circle of a moon porthole, the triangle of a bow, the undulating line of the sea –, magnified by the poetry of a nocturnal atmosphere with tones gray, black and mauve.

Charles Demuth, PaquebotParis, 1921-1922, huile sur toile, 63,5 x 50,8 cm, Columbus, Columbus Museum of Art © Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio : don de Ferdinand Howald.

Charles Demuth, PaquebotParis, 1921-1922, huile sur toile, 63,5 x 50,8 cm, Columbus, Columbus Museum of Art © Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio : don de Ferdinand Howald.The promises of the journey

The second part of the route invites you to leave dry land to get on board. In a cozy atmosphere, a limited but dazzling selection of works and objects evokes the interior splendor of ships. Absolute masterpiece of Art Deco, Normandie is once again in the spotlight, with the engraved glass panels by Jacques-Charles Champigneulle for the large living room and the lacquerwork by Jean Dunand in the first-class smoking room. In a window, pieces of Christofle goldsmithing and Lalique glassware bear witness to the refinement of tableware.

Eileen Gray, Deckchair1926-29, wood, metal, synthetic leather, 79 x 56 x 98 cm, Paris, Center Pompidou. ©RMN press photo.

Eileen Gray, Deckchair1926-29, wood, metal, synthetic leather, 79 x 56 x 98 cm, Paris, Center Pompidou. ©RMN press photo.But the real subject here is the adventure of travel. “ Until the development of commercial aviation, liners were the only way to connect Old Europe and America. They actively participate in cultural exchanges. American artists discovered the European avant-gardes, others marveled at the modernity of skyline. With nineteen crossings made between 1915 and 1955, Marcel Duchamp is undoubtedly the one who best embodies the traveling artist, straddling the two continents. », explains co-curator Adeline Collange-Perugi.

Marcel Duchamp, The Suitcase Box1966, red leather box containing miniature replicas (color reproductions, photography, scale models) of his paintings, watercolors, drawings and readymades, representing all of his work from 1936 to 1941, open box: 4 × 95 × 120cm. Lyon, macLYON Collection. Photo: JB Rodde, © Association Marcel Duchamp / Adagp, Paris 2024.

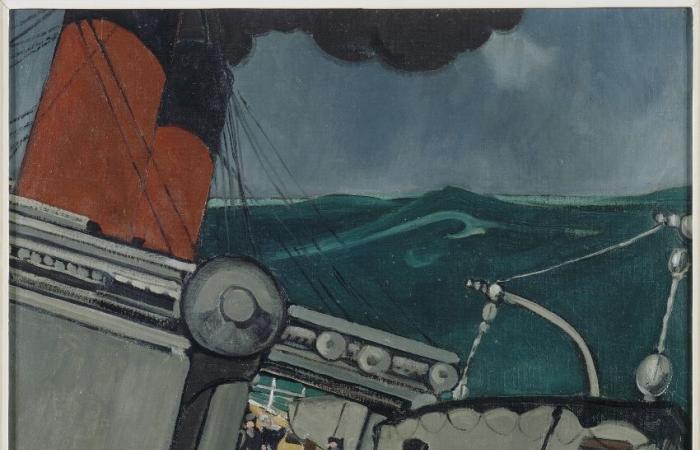

Marcel Duchamp, The Suitcase Box1966, red leather box containing miniature replicas (color reproductions, photography, scale models) of his paintings, watercolors, drawings and readymades, representing all of his work from 1936 to 1941, open box: 4 × 95 × 120cm. Lyon, macLYON Collection. Photo: JB Rodde, © Association Marcel Duchamp / Adagp, Paris 2024.Life on board is documented by advertising brochures and photographs carefully staged by the companies to attract a wealthy clientele eager for pleasure and entertainment (bars, performance halls, swimming pools, etc.). On the other hand, few painters have immortalized the sea voyage. It will especially inspire cinema and literature, evoked in an alcove where images from films by Walter Ruttmann, Buster Keaton or Man Ray are shown, accompanied by extracts from texts by Paul Morand, Colette, Louis Chadourne or Blaise Cendrars.

Jean-Émile Laboureur, The Transatlantic Roll1907, oil on canvas, 55 x 55.6 cm. Nantes, Nantes Arts Museum © Nantes Arts Museum, photo: C. Clos.

Jean-Émile Laboureur, The Transatlantic Roll1907, oil on canvas, 55 x 55.6 cm. Nantes, Nantes Arts Museum © Nantes Arts Museum, photo: C. Clos.If the liner appears as an enchanted parenthesis in the golden age of the Roaring Twenties, it joins the tragedies of great history during the Second World War, becoming synonymous with flight and exile. Many ships are requisitioned. Renamed Lafayette and transformed into a troop transport by the Americans, the legendary Normandie caught fire and sank in New York Harbor on February 9, 1942. A dream came to an end.

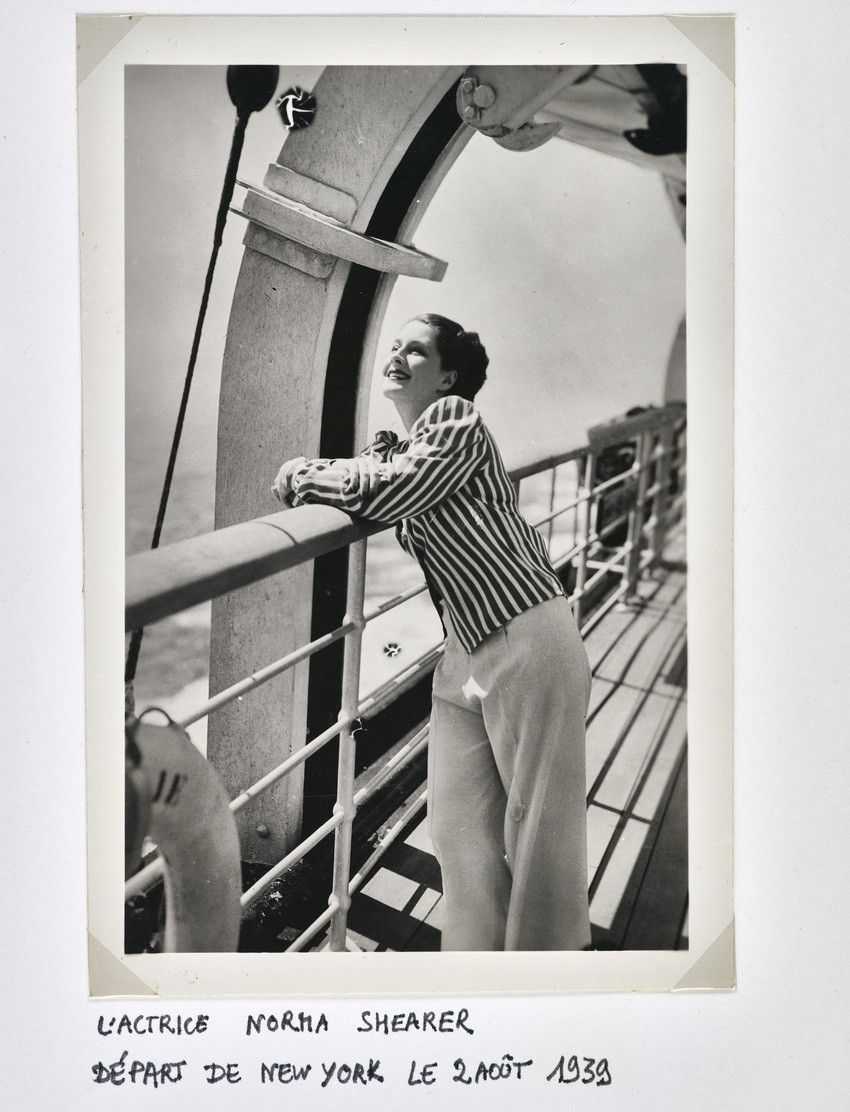

Anonymous, Canadian actress Norma Shearer on the deck of the liner Normandie during a crossing to New York on August 2, 1939, gelatin silver print, period print, 14.4 × 9.6 cm.

Anonymous, Canadian actress Norma Shearer on the deck of the liner Normandie during a crossing to New York on August 2, 1939, gelatin silver print, period print, 14.4 × 9.6 cm.