These two works involve Stanford University and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH, Bethesda), including the laboratory headed by Professor Yasmine Belkaid, now general director of the Institut Pasteur.

The skin, an underestimated organ, is actually an important site for immune defense. Researchers have discovered that the skin is colonized by a harmless bacteria, Staphylococcus epidermidiswhich is present on the skin of almost all people. This bacteria has the ability to trigger a strong immune response, which leads to the production of antibodies that can prevent infections.

1- Develop the antibody production apparatus in the skin in response to S. epidermidis

A first study carried out by Dr Inta Gribonika in the laboratory of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH, Bethesda) directed by Professor Yasmine Belkaid, now general director of the Institut Pasteur, in conjunction with the University of Stanford.

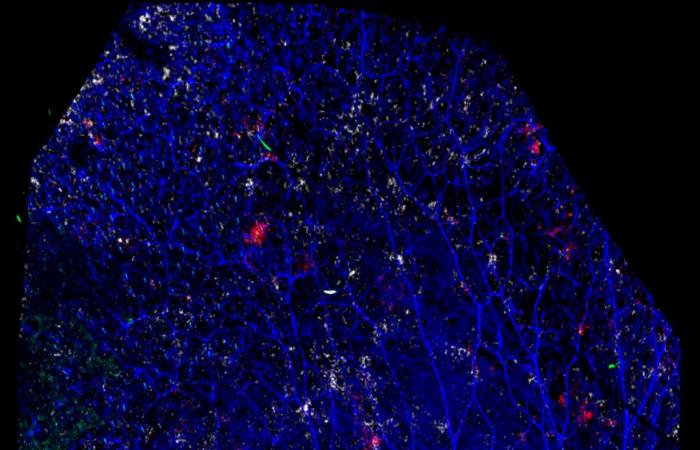

In a recent study led by Dr. Inta Gribonika, a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Prof. Yasmine Belkaid, immune sentinel cells, called Langerhans cells (LC), were identified as a means of alerting the rest of the immune system of the presence of S. epidermidis on the skin. During non-invasive application to the skin with this so-called commensal bacteria (from the microbiota), LC initiate a humoral response through the activation of T and B cells located in the dermis, which leads to the production of antibodies. robust, specific and durable in the skin.

“Observing B cells in the dermal layer of the skin (in the absence of disease) is a novel concept because, until now, skin was thought to be devoid of B cells,” says Inta Gribonika. And that’s not all, because the production of antibodies in the skin occurs in the total absence of inflammation and independently of the contribution of the lymph nodes, which requires a reassessment of the classic model of the initiation of the immune response. Several key biological concepts are therefore called into question here.

The observation of B cells in the dermal layer of the skin (in the absence of disease) is a novel concept because, until now, skin was thought to be devoid of B cells.

While GribonikaPostdoctoral researcher in Prof. Yasmine Belkaid lab

The main discovery of Inta and Yasmine’s work is that, in these specific circumstances, the skin can provide all the necessary means to form a local dermal lymphoid structure that can support a so-called “germinal center” reaction: “This means that a structure in the dermis of the skin is capable of supporting the mechanism of formation and differentiation of B cells into antibody-secreting plasma cells,” explains Inta. The antibodies generated by this process are very protective in controlling the topical colonization of bacteria, ensuring the balance and continued diversity of the skin microbiome. These skin-derived antibodies are also very potent in clearing systemic infection if the colonizing commensal bacteria manages to break down the skin barrier. “This is an innovative and very powerful health protection mechanism that actively protects the host at all times, whether healthy or sick,” emphasizes Yasmine Belkaid.

It is a novel and very powerful health protection mechanism that actively protects the host at all times, whether healthy or sick.

Yasmine BelkaidPresident of the Institut Pasteur

Inta’s work reveals an active dialogue between skin B cells and the microbiota, with important consequences – ranging from a better understanding of the homeostatic control of host-microbiota interactions, which can serve as a platform for approaches innovative vaccines, to new clinical applications for the treatment of topical skin diseases. Together, this work opens a door to a new area of cutaneous humoral immunity.

2- Transform a ubiquitous skin bacteria into a topical vaccine

A second study carried out by Stanford University, in conjunction with the laboratory of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH, Bethesda) directed by Professor Yasmine Belkaid, now general director of the Institut Pasteur.

Yasmine and Inta also co-authored another study led by the laboratory of Dr. Michael Fischbach at Stanford University, in which the systemic antibody response to a genetically modified skin commensal microorganism is assessed, in mice, as an effective topical vaccination strategy.

The researchers used the bacteria S. epidermidis to create a topical vaccine that can be applied to the skin. They found that applying this bacteria to the skin of mice triggered an immune response similar to that observed in humans. These animal models produced antibodies that protected against infection with tetanus and diphtheria, two serious diseases that can be fatal if left untreated.

The tests showed remarkable effectiveness in preventing tetanus and diphtheria infection. Researchers believe this vaccination approach could be used to prevent a wide range of diseases, including viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites.

This discovery opens new perspectives for the prevention of infectious diseases and could revolutionize the way we protect ourselves against pathogens. Researchers hope that this vaccination approach can be tested on humans in the coming years.

Sources

1- Skin autonomous antibody production regulates host-microbiota interactionsGribonika I et al., Nature. 11 December 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08376-y.

2- Discovery and engineering of the antibody response to a prominent skin commensal,Djenet Bousbaine et al., NatureDecember 11, 2024. doi: 10.1038/s41586-024-08489-4