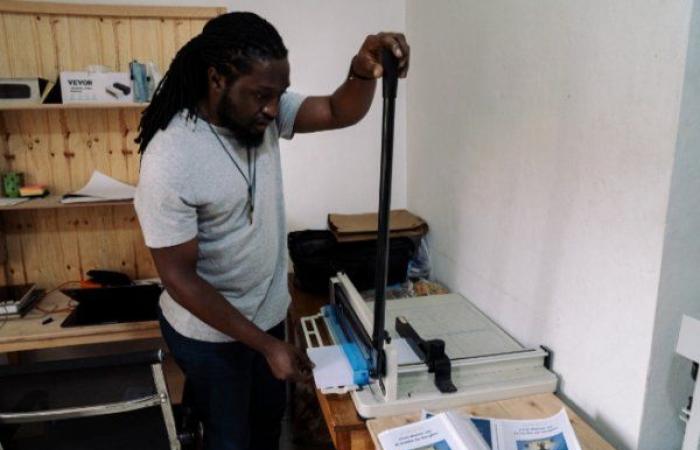

The printer keeps vibrating in the corner of the room. An order of 400 copies is occupying Martin Lukongo's printing house in Goma, a city in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo, better known for the conflict surrounding it than for its literary production.

In a region plagued by violence for more than thirty years, reading is a luxury considered almost futile for some. But a collective has undertaken to reconcile young people with books by producing them in Goma.

“Writers prefer to print in Europe, because they don’t think they can get this quality here,” explains Martin Lukongo.

However, despite power cuts and the lack of quality paper, this professional photographer manages to print around sixty copies per day.

However, buyers are rare in the city's few bookstores. The price of books imported from Europe usually ranges between $20 and $60.

“Very few young people can access these books, unlike other products like beer, on sale every weekend,” laments Depaul Bakulu, one of the founders of the Mlimani publishing house.

A “danger for young people”, according to him, which led a collective of artists and activists to launch an online fundraiser to finance the creation of this local publishing house, which offers books at a price ranging between 5 and 10 dollars.

A year and a half after its launch, the Mlimani catalog has around ten authors published or republished: Frantz Fanon, Nobel Prize winner Denis Mukwege and novelists, researchers or essayists, mostly Congolese.

Their common point: “books which talk about the culture of young Congolese or which have a direct relationship with their lives”, explains Depaul Bakulu.

“They say that the Congolese do not read, but we realized that the problems were much more linked to supply,” he continues.

“Revolt”

Mlimani books are distributed in most major cities in Congo via a network of partners, who collect readers from schools and cultural centers, leading collective reading sessions.

That morning, a dozen curious people gathered in an association center in downtown Goma to discuss one of Mlimani's latest publications: “The general history of the Congo” by the Congolese historian Isidore Ndaywel E Nziem .

“The idea is above all to sit around a table and discuss subjects that concern us. This allows us to disseminate the content without forcing people to buy the book,” explains Victor Ngizwe, a student who runs the 'workshop.

The participants are mostly young men, who describe themselves as committed and hope to find intellectual tools to “revolt and know what to do about the future” in a country immersed in conflicts for decades, explains the One of them, Steven Sikubwabo, a law student.

The evocation of the great pages of the history of the Congo by two volunteers quickly enlivened the debates. A story mainly written by foreign authors, in books published and sold abroad. And rarely passed on to new generations.

“At school, teachers hammer home European history. We don't talk about African Antiquity, we don't talk about the Middle Ages in Africa,” laments Gautier Barweba, slam artist.

“In every civilization, the past serves as a mirror to the present. We need to build myths that can unite us,” adds Victor Ngizwe.

Congolese authors judged to be more “patriotic” or better able to share the “feelings” of readers are thus acclaimed.

Other projects from local publishing houses appeared after Mlimani.

“It’s encouraging for young readers, but also for those who are ready to write,” says Martin Lukongo. “You don’t have to send your books elsewhere to be able to sell them here.” (AFP)